This year’s annual meeting of the Society of American Archivists took place in Washington, DC. Many of my session reports first appeared on the SNAP blog as session recaps.

Some general thoughts about this year’s conference:

The Society of American Archivists (SAA) meets annually, but every 4th year the meeting is held in Washington DC. This was the third time SAA had a joint meeting with the Council of State Archivists (COSA) and the National Association of Government Archives and Records Administrators (NAGARA). The meeting in Washington DC usually receives the highest attendance, and this was the largest meeting on record (exact attendance to be announced — but there were 2,300 pre-registrations . Many thanks to the SAA office staff, director Nancy Beaumont, the COSA/NAGARA/SAA program committee, and the Washington DC local arrangements committee for putting on such a great conference!

I approached this conference somewhat differently than I have in years past. I tweeted less and took more notes by hand, attended section and roundtable meetings normally not on my radar, and didn’t feel obligated to attend every single session.

Although I had a jam-packed schedule, I did not feel obligated to attend and do ALL THE THINGS. This ended up being a very good idea — I was approached a few times during the conference to join panel proposals for future conferences, or to discuss collaborative projects. Because I wasn’t committed to attending something in every single time slot, I was able to have many spontaneous meetings with people. This is good, because I’ll be leaving this conference with many “starts” for future presentations, research, and collaborative partnerships, which will be crucial as I make my way on my library’s tenure track.

I’ve often heard long-time conference attendees mention that the most valuable part of a conference experience happens in the hallways, not in the presentation rooms. After this year, I wholeheartedly agree with this idea. Because I was focused more on seeking out people working on similar projects and research interests, I feel like I strengthened my professional network significantly this year.

I don’t know if I could point to one single theme of this year’s conference. It’s worth noting that the events in Ferguson started over the weekend before SAA, and ramped up over the week (and still are continuing as of this writing). I saw this come up occasionally in the #saa14 Twitter stream as early news reports were lacking in sufficient documentation, and how archivists’ work intersects with documentation to serve social justice. Maybe I’m just seeing what I want to see because I started and ended the week on an advocacy note, but I do think I saw more emphasis on the power of archives this week, to paraphrase Rand Jimerson In many ways, SAA is a big enough conference that it’s a “choose your own adventure” kind of thing, so I gravitated to sessions on strengthening the archival profession and our connections outside our field, rather than solely sessions on technical practice. In other words, my experience of SAA this year was more of a focus on the “why” of archives, instead of the “how.”

A note about some of the reports: you may notice some of my reports on particular meetings or panels are very heavily detailed while others are not. I volunteered to recap a number of sessions for the SNAP Roundtable, so for sessions I was covering, my note taking was pretty intense. You may want to check the #saa14 Twitter hashtag and session-specific hashtags for more information (usually specified such as #s502 or #s411), as well as the SNAP blog for more information on the events during the conference.

Day 1/Monday:

I attended the workshop, “Advocating for Archivists,” taught by Jelain Chubb and David Carmichael. They both have extensive experience in managing state archives, and the workshop purpose was to help archivists develop advocacy strategies. The workshop was interesting because archival advocacy has a lot of overlap with archivist professional identity, how our society values cultural heritage, the increasing use of metrics and ROI, and so on. Advocacy is something that is vital to the archival enterprise, and my favorite archivists also happen to be some of the fiercest advocates I’ve ever met. Some of the takeaways from the workshop for me were:

- It sounds obvious, but you can’t just ask for “space” or “more staff.” You must frame these needs as part of a defined goal.

- Recruit and cultivate people to carry your message for you; these voices often have more resonance than your own (or, “Who do the people you want to influence listen to?”)

- Don’t always stick with the “historical treasure trove” (aka “the trivia trap”) of archives as a selling point — this is not compelling for a significant part of the population. Tell stories about how archives have literally saved lives, saved jobs, stimulate the economy, etc. Give stakeholders reasons to agree with you.

- Appeal to what is right (an unchanging message), but also tune your message to the audience (and their self-interest)

- Think of interesting ways to present your usage — one member of the workshop mentioned that he created data visualizations to show archives use. One of our instructors had done tourism impact studies of out of town visitors to the archives, showing that they spent 4 nights in the state, and generally visited at least one other city for personal travel during their trip.

- Always have a specific “Ask” when you are meeting with someone to discuss your concerns or needs.

We concluded the day with writing an advocacy plan — similar to what I was planning to do anyway for kicking off some digital forensics planning at UC. So it was a very helpful and useful exercise. Many thanks to our instructors and SAA for offering this extremely low-cost workshop — only $40!

I then attended my first SAA Council meeting — or, rather, my first half-hour of a Council meeting. Shout-out to Kathleen Roe for encouraging folks to attend Council meetings, which are open to the public. She did a fantastic job of taking me around to meet all the Council members. Advocacy in action!

I closed out the night by kicking off the first Lunch Buddy (dinner, actually) outing of SAA 2014. Lunch Buddies has been my baby since I helped create it through SNAP a couple years ago, but I let the reins go this year when SNAP fully took over the spreadsheet wrangling. I’m so proud of this effort, and I really hope people will continue to use and benefit from Lunch Buddies in years to come.

Day 2/Tuesday:

I attended a few papers at the annual meeting research forum. I really enjoyed Christine George’s paper titled, “You’ve got a Better Chance of Finding Waldo: Archivists in Pop Culture and Why Their Lack of Visibility Matters” regarding the lack of archivist visibility in pop culture was intriguing. I took the rest of the afternoon off to attend the wonderful Andrew Wyeth exhibit at the National Gallery, and to also do the world’s quickest stop at the National Archives to catch a glimpse of the Constitution.

Day 3/Wednesday:

I kicked off the day with a run by the National Cathedral, and then I led a Lunch Buddy trip to the National Zoo in order to see the Zoo’s pandas. We saw a couple — one in a tree, and another chowing down on bamboo for breakfast. I got back in time for the latter half of the SAA Leadership Orientation and Forum, something I thought I should attend because I’ve recently been elected to SAA’s Records Management roundtable. Then it was off to a meeting for Nominating Committee, as we continued to hash out our slate of candidates for the 2015 elections.

In the afternoon attended the International Archival Affairs Roundtable, which is not something that is often on my conference schedule, but was pretty awesome! In attendance were representatives from the International Council on Archives (ICA). ICA is engaging in some interesting activities to develop opportunities for new professionals, and also developing resources for African archives and archivists. Then we heard from Bill Maher, SAA’s representative to WIPO. Some of the copyright conversations at WIPO collapsed this year. You can read more about that here.

I attended the joint meeting of the Lone Arrangers and SNAP Roundtables. The two main content presentations of this were two separate panels on being an archives consultant, and archival internships from the supervisor’s perspective. As topics on archival employment, education, and internships frequently do, there was fairly lively discussion.

Later I led a SNAP Lunch Buddy group up to the fabulous restaurant Ted’s Bulletin, where several of us got food before a night out on the town.

Day 4/Thursday:

I had a fantastic meeting with my Navigatee. This is a service that SAA provides to match up new conference goers with seasoned attendees. We had a great conversation about some of our shared interests, and discussed how to get the most out of the conference. I highly recommend that all veteran SAA-goers offer to serve as a navigator at future conferences (and you don’t have to be super-experienced — I think most people could step into this after about 3 conferences). Conference first-timers, be sure to sign up to be matched with a navigator!

The first session I attended was Session 107: Archivists AND Records Manager?! This session focused on the challenges faced by dual-title individuals (i.e., Archivist/Records Manager), as well as archivists who encounter records management concerns unexpectedly (and vice-versa). The session opened with an introduction to the Records Management for Lone Arrangers guide Lisa Sjoberg (Concordia College) shared the rests of a survey that was conducted on dual archives & records management programs. These programs are usually based on a centralized or decentralized model. The survey was mainly distributed to archivist listservs, which may have influenced the results. Major concerns expressed by individuals who administered joint archival/RM programs were electronic records, and how to strengthen compliance and cooperation with program goals.

The other participants Holly Geist (Denver Water) and Alexis Antracoli (Drexel University) talked about some of the challenges of doing records management and archival work in parallel. A fun fact I learned from this session — apparently Denver Water coined the term ‘xeriscaping’. The main takeaway from their presentations is that the impact of electronic records has sometimes made it difficult to ensure records management practices are being adopted uniformly across all areas. Geist had a brilliant tip for how to ensure records are not lost when someone leaves the institution — regularly get a retirement list from HR so retirees may be contacted to ensure proper disposal and/or transfer to archives of their records before their departure.

This was the first year I attended the Academy of Certified Archivists (ACA) business lunch. I took the ACA exam last year and passed, and thought it’d be interesting to see how the Academy conducts its business and what the governance structure looks like. As part of my research on job ads, I’ve read a lot on the origins of archival certification, and its relationship to professional identity and archival education. As this was the 25th anniversary of ACA, there were brief presentations by long-time ACA members on the history of the academy and its future.

Gregory Hunter made the following points in his presentation, which closely mirrored much of what I’ve read from archival literature:

- 1989 was not the beginning of archival certification — a significant amount of groundwork had been laid before then, and the idea of archival certification had been around for some time

- The ACA would not have come into existence without the altruism of its early founding members, many of whom poured significant time and resources into its founding

- At the time the ACA was founded, certification was viewed as a first step, and not the last step within the archival profession. Many archivists at this time supported not only individual certification, but also the accreditation of graduate educational programs and the accreditation of archival repositories.

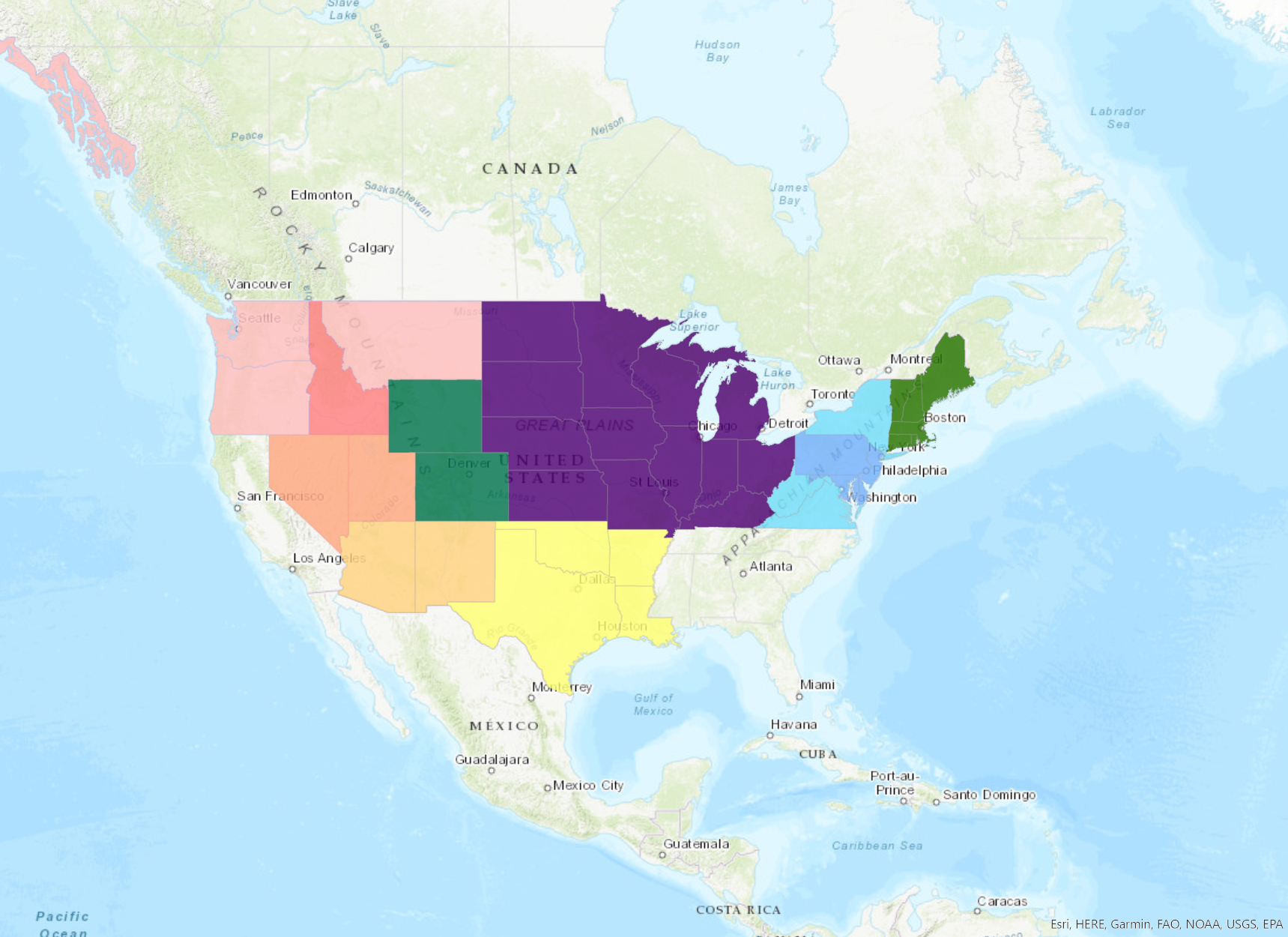

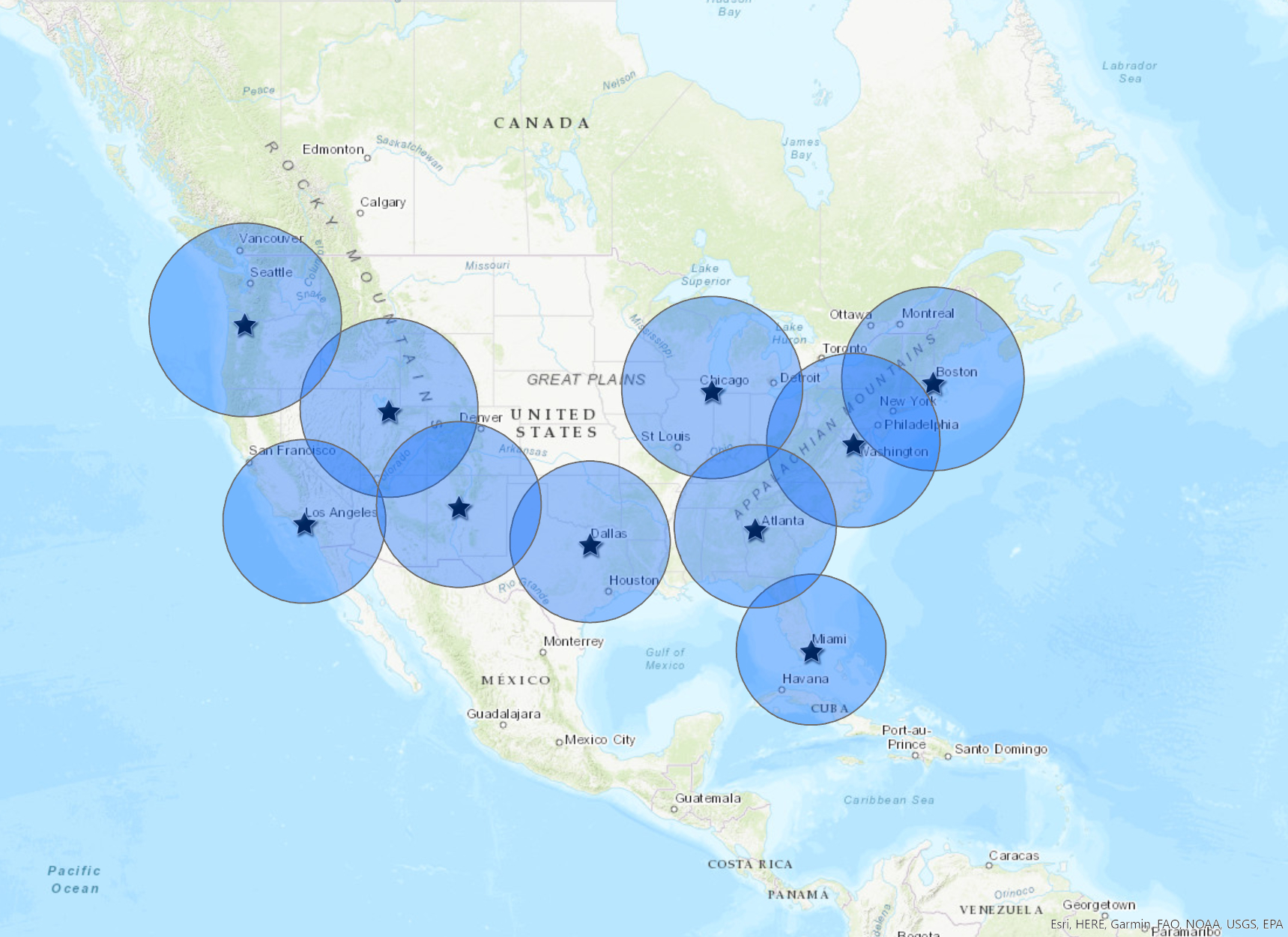

Mott Linn recently conducted a large survey on the geographic distribution of certification. This was fascinating, as it confirmed much of what I’ve long suspected based on anecdata seen over my own early archival career.

Something that has continually surprised me is what a polarizing issue archival certification is, and how often it seems to break down along geographical lines. My first post-college archives gig was five years at Tulane University in New Orleans. Louisiana is in the Society of Southwest Archivists (SSA) region, and it always seemed to me that SSA is a core stronghold for Certified Archivists. Many prominent archivists in this region have their CA, and when I started at Tulane, I was expected to sit for the exam as soon as I qualified (i.e., finished my graduate degree). When I was preparing for the exam, I helped run a very informal study group for all the local archivists planning to take the exam when SAA met in NOLA in 2013. When I’ve encountered outright hostility to the concept of archival certification (some of the feelings understandable, others not so much), I’ve almost always found it coming from archivists who were educated or had their first job outside of the SSA region (or to put it bluntly and less diplomatically, from the upper East Coast, mid-Atlantic area, and some parts of the Midwest).

Linn’s research on this issue will appear in a forthcoming issue of American Archivist. I hope that he includes as many of the fun color-coded maps as were in his slide deck. As someone whose undergrad work was in urban geography, this was a great presentation. Here were some of the highlights —

- The Mississippi River appears to be the major dividing line between who has the CA designation and who does not

- There are 15 Certified Archivists (CAs) per 100 Society of American Archivist members (SAAs) east of the Mississippi River

- There are 30 CAs per 100 SAAs west of the Mississippi River

- In the Society of Southwest Archivists region, there are 40 CAs per 100 SAAs (to which beloved Dr. Gracy shouted out his trademark ‘Hot dog!’)

- A figure which will likely not surprise anyone, the weakest area for CA membership is New England

I really look forward to seeing this work published. While I have some issues with aspects of archival certification (the steep exam fees, the exam structure), I do think there is continuing value in certification. I tend to be a “don’t throw the baby out with the bath water” reformer, rather than a “burn it down!” revolutionary. I have significant concerns about the monetary costs associated with certification, and this concerns me because I worry about how financial barriers prevent and actively discourage our profession from reaching a real form of diversity. While I support time and study barriers as qualifiers for entering the profession, I think financial barriers have real effects on our goals of diversifying the archival workforce. I hope this is an issue we can address, not only within ACA but elsewhere in our professional organizations. As someone astutely noted, as expensive as the ACA exam can be, it’s still cheaper than the full set of SAA’s DAS courses.

Later on Thursday afternoon, I attended Session 203: Talking to Stakeholders about Electronic Records This was a fun, interactive session in which we discussed how to make the case for electronic records management issues to three groups of stakeholders (records creators, administrators, and IT). The content of this panel was quite similar to the advocacy workshop I took earlier in the week. Our presenters started off with these introductory points to keep in mind:

- We know electronic records are important and need certain forms of management, but do others?

- There is not a “one size fits all” approach to making the case. Depending on the type of stakeholder, different messaging strategies will have more meaning. Identifying shared interests between the archivist/records manager and the particular stakeholder is the key to a successful relationship. In addition, always trotting out a “doomsday scenario” is not always a great way to get buy-in

- We have ignored the heavy lifting needed for managing electronic records for too long, and we can’t do it anymore

Jodie Foley of the Montana Historical Society noted that when it comes to advocacy, it’s not “one and done,” but it is critical to sustain relationships over time. When it comes to the concerns of records creators, shared interests often revolve around legal concerns (I have heard this in my own work — people are terrified to get rid of anything lest they find they need it for a future lawsuit), efficiency across business processes, and managing records well so they can be easily located. Foley talked about the perception among some records creators that records managers often “get in the way” and how our outreach must be conscientious of this perception. Records creators may think “IT is taking care of it.” When we counteract this message, we must also emphasize that we work in cooperation with IT — not that we are antagonists, or competing with them. Obviously this must go beyond messaging to forging real relationships with IT — more on that in a minute.

As part of this panel, we would break off into discussion groups to work through a set of scenarios, and then reconvene to share our talking points, and move on to the next speaker. After Foley spoke, we broke into groups to discuss the first scenario: explaining how to manage electronic records to a state’s Department of Transportation. We worked through talking points, and then each discussion group came together to share their best ideas:

- It’s in their best interest to identify and manage vital records early as part of disaster prevention

- Good electronic records management can help your area avoid embarrassment

- Empower others to “CYA”

Next, Jim Corridan of the Indiana Commission on Public Records spoke to us about how to craft messages for administrators. The concerns of this group is also centered on legal compliance, and business efficiency. In addition, they are also significantly concerned with a public relations disaster and a hit to institutional reputation. They also may be pressured to respond to calls for increased transparency and accountability. One concept I heard frequently in this session was “tripping points,” which I took to mean a form of challenges one might encounter in the advocacy process.

Corridan was very clear that using historical value as a selling point is often not effective with many administrators, since history is seen as a luxury. He suggested that an effective formula to use with administrators (and likely, all stakeholders) is “Here’s a problem, here’s a solution, here’s how we can work together.” We returned to our discussion group to discuss messaging for a scenario of a public university panel considering new projects, and pitching the archives’ need to transition to managing electronic records. Ideas from our group and others included:

- Noting that the archives has a statutory mandate to manage records, but that without the support needed to make electronic records, we’re not in compliance

- Universities view themselves as cutting edge — do they want to keep doing things in a way that is no longer satisfactory?

- Look at what “competitor” schools are doing

The final group of stakeholders we considered were IT. Information Technology teams have specific concerns around storage and management costs (often fee-based in many organizations), security standards, system efficiency, etc. IT has its own definitions that often depart from archivist/records managers’ definitions (e.g., “archive,” “governance”). It can be useful to look at what work is happening that intersects with RM from influential IT organizations such as NASCIO In other words, find out who your institution’s IT people listen to. Because CIO positions often have frequent turnover, this presents a challenge for building relationships. The last scenario our discussion group considered was how a state archive might gain IT support for why electronic records need special consideration beyond normal practice. The ideas generated in the room included:

- Emphasizing that we can help reduce IT burdens by identifying what can be removed from systems

- Framing collaboration with IT as a new and exciting project. Help them share in the glory of success.

- Do a self-assessment before approaching IT so it’s clear what your needs are and how they can help

This was a great session, and what I liked about it was the participatory nature. The panelists left us with some final thoughts:

- Go for low-hanging fruit to snowball successes

- Do your research about hot-button issues in your organization you might not be aware of

- COSA/NAGARA/SAA are going to begin some joint advocacy efforts for electronic records

- Keep an eye out for the next Electronic Records Day— held annually on October 10 (1010 — get it? If not, read up on binary code)

The final official thing of the day I attended was SAA’s Acquisitions and Appraisal Section meeting. Appraisal is arguably the most critical function performed by an archivist, since it is the major step in shaping what historical record survives and what is designated for destruction. Some archivists say that good archivists know what to keep, better archivists know what to destroy. I’ve often thought appraisal is what distinguishes archivists from hoarders.

This is a section meeting I normally have not attended in the past, so it was interesting to see what was on this section’s radar. They announced the creation of a new blog, and the main portion of the meeting featured a number of panelists discussing tools that assist with appraising and accessioning electronic records. The following tools were highlighted:

- BitCurator— a packaged set of tools to create digital forensic disk images, and tools to work with those disk images

- An as yet unreleased tool to acquire electronic records out of Dropbox, in development at NYU

- Archivematica— tools for processing electronic records, including normalization and format identification

- ePADD— a tool that detects email patterns

- Various tools from AVPreserve

Day 5/Friday:

The first order of the day was to attend the Write Away! breakfast. I attended because I am interested in pursuing research and writing opportunities. This breakfast featured some of the publications board staff and editors affiliated with SAA’s publication outlets (American Archivist, various publications, and Archival Outlook). Chris Prom, SAA Publications Editor, shared news on efforts to publish case studies by SAA Component Groups, and future editions of Trends in Archival Practice. Greg Hunter, editor of American Archivist, discussed the journal, noting that there are currently 150 peer reviewers associated with it. He mentioned that because the journal is now over 75 years old, he is interested in retrospective articles on a variety of topics (e.g., “75 years of appraisal in American Archivist”). Amy Cooper Cary, Reviews Editor, noted that anyone can get in touch with her if they are interested in reviewing a book or another resource. Although only a few reviews make it into each issue of American Archivist, additional reviews are published on the reviews portal.

Later, I attended Session 305, Managing Social Media as Official Records Lorianne Ouderkirk of the Utah State Archives and Records Service discussed the educational and operational challenges of applying records management guidelines to social media. She noted that people now expect to be able to communicate with government through social media, which has led to a significant rise of governmental entities using various social media channels. These can be hard to keep track of, although in Utah there is an excellent dashboard which lists all the various state agency social media channels. The Utah State Archives has situated education on social media records around the following factors:

- Risk

- Identifying records

- Applying retention

In addition, they have issued a draft document titled Preliminary Guidance on Government Use of Social Media. These guidelines were adapted from the New York State Archive’s guidelines. Ouderkirk noted that in Utah, most records fall under existing records schedules under Correspondence, Publication, Core Function, etc. She noted that over the course of training, most attendees wanted information on agency guidelines, but after a follow-up, many found they did not have time to implement what was learned in records training.

The next speaker was Geof Huth of the New York State Archives, who discussed the risk aspects of agency social media use. He showed some fairly amusing (and redacted!) screenshots of social media activity from state agency and political offices. It is not unusual for constituents to leave vulgar and/or highly-politicized rhetoric on social media channels. Although not all social media may constitute a record, many social media postings, pictures, and status updates do constitute a record. Huth noted that not only does government use of social media tell us how government functions, but also about how government wants to be seen.

One of the biggest stumbling blocks with social media is that there is no such thing as true local control, because the use of social media necessarily involves using a third-party application. Social media use has the potential to be inefficient, increase an agency’s vulnerability to cyber attacks, risk of public embarrassment, and an inability to produce records if called upon to do so quickly. Huth stressed that when possible, it’s important for agencies to take control of their data, presumably via some form of export to local systems and active management.

Huth stressed the necessity of the following policies and procedures:

- Determining content creation issues — do all postings require approval by an agency head or delegate before going public?

- Appropriate use — who at an agency gets to create social media postings?

- Security — who has the password? How will risks be monitored?

Determining “what is a record” can be difficult among any group of records, but applying records definitions to social media presents its own set of challenges. Some of the options are to either treat a social media channel/site as one entire record, or examine content of each record to determine retention/disposition.

When considering capture of social media records, the following questions must be considered:

- Should records be retained for a long or short time period?

- How frequently should records be captured?

- Quantity — do you need everything or simply a sample?

- What should be done if it turns out the popularity of a social media channel is short lived?

- Is it possible to extract only the data you need?

Huth reminded us that “capture is not preservation,” and agencies may want to consider specialized tools — there are some open access tools for web harvesting and social media capture (for example, Heritrix and Social Feed Manager , as well as commercial tools such as ArchiveSocial and RegEd.

The final speaker of the panel was Darren Shulman, attorney for the city of Delaware (Ohio), on implementing a social media plan. Full disclosure, I have the privilege to serve with Darren on the Ohio Electronic Records Committee. Darren walked us through creating a social media plan, which can help guide records-related decision making. Ideally a plan should be created before a social media channel is adopted. A social media plan can help with the following issues:

- Security — who has the password? This is important information in case of staff turnover or cyberattack.

- Roles and responsibilities — defining the roles of records management, business units, legal, and IT

- Moderation and participation — how will responses be monitored?

Darren noted the following distinctions between things an agency posts, versus things other people post:

With things you post:

- Is it a record, or a copy of something that was originally posted elsewhere?

- If it is a record, how will you maintain it?

With things other people post:

- Are comments a public record?

- How to treat vulgar comments? There are a few options:

- Delete

- Leave up, with a visible disclaimer

- Capture for internal records and then delete from public view (this was a suggestion from the audience, but may pose issues unless you have a posted policy somewhere)

- May constituents use social media channels as a way to make a report or file a complaint?

If anyone would like to download the social media plan, you can find the template here.

After lunch I headed to Session 501: Taken for Granted: How Term Positions Affect New Professionals and the Repositories That Employ Them Grant-funded temporary positions (aka “project positions”) are prevalent in the archival profession, and are often funded for somewhere from 1-3 years, and occasionally longer. The panel consisted of early-career archivists who discussed their project positions, hiring managers who had hired many project archivists, and a representative from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, which provides a significant number of grants to fund temporary processing projects at American institutions.

The two early career archivists discussed the challenges of being a project archivist — often times the critical difference for their job satisfaction was a manager who helped them access professional development funding, and helped integrate them into the overall infrastructure of the archive’s operations and administration. Mark Greene, director of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming, echoed this sentiment, noting his efforts to invite project archivists in his center to all department meetings, and many others. He has built in professional development funds to temporary position salaries, and has attempted to (it sounds as if there are HR or agency barriers) also factor in salary increases.

Dan Santamaria, recently of Princeton, gave a fairly sobering presentation on his experience with hiring over 30 project archivists over a 10 year period. He noted that not only does this lead to a workplace with two classes of archivists (permanent and temporary), but it is also an enormous time burden on a hiring manager to always be in some state of hiring or training. Santamaria noted that for the vast majority of employees (permanent and temporary), it takes them about 6-12 months before they feel comfortable and familiar with the workplace. Of course, by that time, a project archivist may be getting ready to move on. Due to this turnover, Santamaria noted that he experienced approximately 4 entire team turnovers during his time at Princeton. Santamaria noted that the past model of project work (assuming one archivist working on one collection) may no longer be as relevant in some repositories, and urged the profession to reconsider offering project positions just because we can.

Finally, Alex Lorch of NHPRC, noted that processing grants means jobs, even during the recent recession. He reviewed his own job history (which included some temporary positions), and noted that ‘project archivist’ does not always connote entry-level work. He included some tips for grant applications — you have to write a job description for each grant, justify the salary, and keep in mind it’s common for project archivists to leave before the grant is up (due to the necessity of job searching before the grant is over), and that it takes a lot of time to screen applicants.

The last session of the day was the SAA Records Management Roundtable. In the interest of disclosure, I was recently elected to the Records Management Roundtable steering committee. Unfortunately I got there about 20 minutes late due to a scheduling snafu, so I missed the first few items of business. The roundtable will soon be voting on new bylaws, including that of the continuity of vice-chair/chair-elect/immediate past president, and staggering the steering committee elections. Currently the entire roundtable leadership is re-elected each year, which leads to some confusion and inefficiency. A proposal was made from the floor to elect 6 steering committee members, 2 each on a 3-year cycle. We were also asked to consider whether we still need a newsletter considering the roundtable has a blog, Twitter, and microsite.

Following the business meeting, we moved into the “unconference” portion of the meeting. We broke off into self-selected groups to discuss various topics that had been posed. I chose to join the group to discuss “getting records management buy-in at your institution.” My group consisted of archivists at public and private universities, as well as those working in the corporate sector, and within a federal agency. An archivist from a large Midwestern university noted her efforts to implement a records management program, which took about 10 years to get fully off the ground. She said her persistence and strong relationships with IT (especially when they have the purse strings) were key to her success. The archivist from the federal agency noted how a colleague of his at another branch had a “Biggest Electronic Loser” contest to award employees who disposed of the most electronic data. I also ran some of the ideas I had about increasing records compliance at my university past this group. They enthusiastically endorsed my ideas, and offered some good advice.

Towards the end of the slot, we all shared some of what we discussed with the larger group. Luckily all of these notes were captured in this crowdsourced document representing the work of each discussion group. Check it out! The Records Management Roundtable has an active presence during the year. You might want to check out some of the Hangouts they do, as well as the thoughtful blog, The Schedule.

The evening rounded out with a wonderful reception at the Library of Congress (poking around in the old-school library card catalog with a bunch of archivists might be the night’s highlight) and the revival of Raiders of the Lost Archives. You can check out some of the tweets for the Raiders program here.

Day 6/Saturday:

The last day of SAA always feels mellower than the first couple days — probably because a lot of people have already left, or energy levels are lower? Not totally sure. I attended Session 705, Young, Black, Brown and Yellow: Diversity Recruitment Practices from the Field. The panelists discussed the Knowledge Alliance program to recruit a diverse workforce to librarianship and archives. The panelists emphasized the importance of connecting with people’s individual interests, and the impact of having librarians and archivists of color in visible positions. Often, students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups simply don’t have these fields on their radar, and it makes a large impact to have contact with a librarian or archivist who looks like you. Tabling at career fairs is critical — students can’t be recruited into librarianship and archives unless they know it even exists at a job fair. Steven Booth shared a great anecdote about a student who showed interest when she asked if his work was similar to Olivia Pope’s father’s cover.

The panelists also noted that recruiting student workers and paraprofessionals is also an excellent way to develop a diverse professional workforce. These individuals are already exposed to library and archival work. Booth told us that if a library is interested in diversity recruiting strategies, to contact diversity@ala.org.

The final meeting of the day was the Annual Business Meeting. Every year I get on Twitter and exhort people to show up at the business meeting if they are still in town. I feel quite strongly about this, because I have occasionally witnessed business meetings where an action is being taken that might disproportionately affect newer and/or underrepresented members of the profession, but few members of those groups are often at the business meeting. Unlike in previous years, our quorum threshold was met right away (usually this is measured by seating all members in a roped-off section of the room).

Shortly after the meeting was called to order, Executive Director Nancy Beaumont shared some very sad news with us — Nadia Seiler, a manuscripts cataloger at the Folger Shakespeare Library — was en route to the conference when she was struck and killed. Her fiancé had alerted the conference staff to share this news. We held a moment of silence in her memory. I had not met Nadia, but my heart goes out to her friends and loved ones.

We adopted the meeting’s agenda with no items added from the floor. Nancy Beaumont took the lectern to deliver her annual report as Executive Director of SAA. The highlights of her speech noted how SAA was meeting the goals outlined in the current strategic plan:

- On the advocacy front (Goal 1 from the Strategic Plan), the Committee on Advocacy and Public Policyand the Committee on Public Awareness have been convened, and advocacy resources for SAA members to use will be forthcoming

- On enhancing professional growth (Goal 2), the DAS program now has over 89 individuals who have passed the exam, and over 800 pursuing the certificate

- The final attendance of this year’s conference is yet to be determined, but is estimated to be around 2500 attendees

- On advancing the field (Goal 3), Council has approved best practices for internships, and best practices for volunteers

- MetaPress will no longer host American Archivist, a new publishing home is being sought

- Joint Task Forces with ACRL/RBMShave been convened for Standardized Holdings Counts/Measures and Standardized Statistical Measures for Public Services

- A new version of the Archival Terminology dictionary is forthcoming, and a Word of the Week email has been launched

- On Meeting Member Needs (Goal 4), Beaumont noted that the Communication Task Force (on which I previously served) recommendations have helped — there are now more click-throughs on In the Loop, and the Archival Outlookembargo has been dropped

- An SAA Code of Conductwas established, and work is progressing with the Task Force on Member Affinity Groups

- Audio of the 2006-2011 conferences has been posted online, and for $30 you’ll be able to download MP3s of the 2014 sessions

- The membership at the end of FY14 stood at approximately 6,224

- The outgoing SAA officers include Terry Baxter, Beth Kaplan, Bill Landis, and Danna Bell

Next, Mark Duffy, Treasurer, gave his annual report. The highlights:

- SAA’s finances are strong enough to be able to do some levels of experimentation with the annual meeting model

- Staff and administration overhead are a large part of the finances

- Council has agreed to set aside funds for a Technology Reserve fund in the neighborhood of $220,000 to enhance e-Publishing, new communication technologies, etc

- The FY15 budget is 5% larger than FY14, with a 74% increase in advocacy spending

- SAA is exploring new methods of delivering Archival Outlook online, and providing affordable childcare at meetings

- Maintaining all staff salaries at living wages is a priority

- SAA is examining activities it may drop in the future, that are no longer useful to the organization

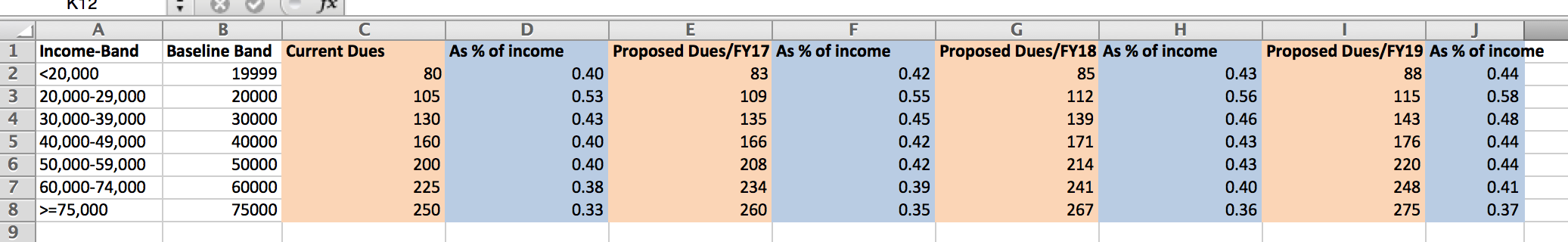

- Membership dues are approximately 30% of total revenue, but membership growth has been limited since 2012. The benchmark goal for membership revenue is approximately 34% of finances, and Mark told us we should expect to hear about dues in the coming year, but did not elaborate further

- The SAA Foundationwill step up its planned giving

Amy Schindler, immediate past-chair of Nominating Committee, reviewed the slate of candidates presented to the membership in early 2014. Full disclosure, I was nominated for Nominating Committee and won. More about Nominating Committee’s work can be found here. Amy noted that this year’s election turnout was 20% — still far too low if you ask me, but better than the previous year’s rate of 17%. Is it too ambitious to hope for a 25-30% turnout in the 2015 election?

Kathleen Roe then took the lectern to deliver her first address as new incoming SAA President. She opened with the song from the musical RENT, Seasons of Love, which counts a year in minutes (525,600 to be specific). If you’ve ever spent 5 minutes with Kathleen, you know that her jam is advocacy, and this will be her theme over the next year. I’m excited — some of the most inspiring literature in our field is centered around archivists’ need to advocate for our communities, our users, our “stuff,” and ourselves. Kathleen reminded us that advocacy is something we know we need to do, but for many archivists it is not yet a natural act. Kathleen invited us to a “year of living dangerously,” as we work to spread the message that archives change lives. I’m fired up and ready to go.

See you next year in Cleveland, friends.

Comments Off on SAA14 trip report