As America’s longest presidential election finally gets underway (particularly in the 34 states that have early voting), and as a voter in the great swing state of Ohio, I have started to think that the best metaphor for voting in this election is that of the social responsibility of mass vaccination. In order to be clear about my personal views, I believe this election is between an experienced politician with profound shortcomings [1], but who fundamentally understands the three branches of government, the interrelationships between local, state, and federal governance, and what the Constitution does and does not allow a President to do. In contrast, her opponent is a man who has never been elected to public office before, or ever served in any civilian or military public service, who exploits frightening bigotry, and who has shown very little understanding of the functions of governance or the Constitution.[2]

During this election cycle, and particularly in Ohio, there has been a lot of grumbling along the lines of “Both candidates are terrible, so I am going to stay home or vote third-party, because neither one reflects my views.” I am distressed by this idea, because it suggests that voting is a personal act, or a personal expression of one’s views. From where I stand, we need to think of voting as a collective action, because it is not an individual act for which one reaps individually allocated benefits or drawbacks (note: this may have been different during Gilded Age machine politics when you could literally get paid for voting for a particular candidate or party). And like any collective action, whether it’s union membership approving a new contract, or an activist group deciding strategies for protest, there is inevitably an evaluation that comes down to: “this contract or action is not going to meet the needs of everyone, but do we think the larger gains that could be realized outweigh the parts that we have discomfort with?”

In the 2016 general election, a terrifying amount is on the line.[3] We have now gone over 8 months without any visible movement towards confirming a new Supreme Court justice, leaving the court with only 8 members. Of the current membership, three of the members are currently over the age of 75 (Kennedy, Breyer and Ginsburg), which means that the chances are pretty good that a second, or even third court vacancy will occur during the next presidential term. Few decisions at the federal level have the potential to shape the American experience more than what comes out of the Supreme Court – Plessy v. Ferguson, which institutionalized racial discrimination, was the law of the land for 58 years before being overturned by Brown v. Board of Education. And this is precisely why the top brass of the GOP keeps gritting their teeth and has taken only the feeblest steps to publicly disavow Trump – because they know that if they are able to control the Supreme Court membership, this is likely their last chance to embed right-wing values into the country’s long-term legal infrastructure, even as the rest of the country is in the midst of a massive political realignment.

To return to my original metaphor – voting is best thought of as not a personal expression of your values, but as a collective action you take on behalf of a larger group. And I think an apt comparison is that of mass vaccination.[4]

Mass vaccination has been one of the most breathtakingly successful ways in which we’ve reduced devastating disease and illnesses that used to routinely strike fear into populations – even within well-developed countries like the US (if you’re young and have never asked an older person what it was like before the polio vaccine – ask. You’ll probably hear some heartbreaking stories about kids they knew who were paralyzed or died). Mass vaccination works because of what is known as herd immunity. In any given population, there are members of the population who cannot receive vaccines, because they may be immunocompromised, or have a potentially deadly allergic reaction to the vaccine ingredients. Therefore, they rely on the rest of us to close off potential entry points for the disease to get into the population. When diseases that were long-thought eradicated pop back up, it’s often because vaccination levels have dropped below a certain threshold. This is dangerous not only for those who could be vaccinated but were not, but especially for those who cannot get vaccinated at all.

Part of the problem with those who decide not to vaccinate against all the advice of the medical and public health communities is that they view this as a personal choice, and not a critical thing they must do for the benefit and health of all. Those who choose not to vaccinate for personal reasons (anti-vaxxers) because of a perceived risk of vaccination are not entirely wrong – any vaccination does have a non-zero risk of side effects. However, the benefits (individually and collectively) of participating in mass vaccination is so overwhelming compared to the risks, that when an increasing number of people prioritize the infinitesimal unlikely personal risk over the overwhelmingly certain public benefit, everyone suffers.

As long as herd immunity thresholds are high enough, anti-vaxxers effectively become free riders. They get to have their cake (benefit from herd immunity) and eat it too (continue to indulge their personal beliefs about vaccination risks). It’s here that I see the most parallels to those who would rather sit this election out, or cast a vote for a third-party candidate, than to grit their teeth and vote for Hillary Clinton.

Like a single vote, a single vaccination is not sufficient to protect one against illness – a disease may mutate and still infect you, or the vaccine may only cover the most common strains of a disease, or you may experience side effects of immunization. However, you incur a major risk by choosing not to vaccinate: you’re rolling the dice that your participation is so marginal that it won’t affect herd immunity, and that the risks of your actions won’t bring about something far worse than you could have imagined, particularly for those who cannot receive a vaccination because of medical reasons.

Let’s look first at the effects of individual actions on a collective decision, because that’s effectively what both vaccination and voting are. If a certain number of people don’t get vaccinated, the herd immunity drops below a certain threshold, and a disease can re-enter the population. Likewise, if enough people don’t vote for a candidate, another candidate will win. And unless you live somewhere with instant runoff voting or alternative voting mechanisms, it’s generally going to be the candidate who is “first past the post.”

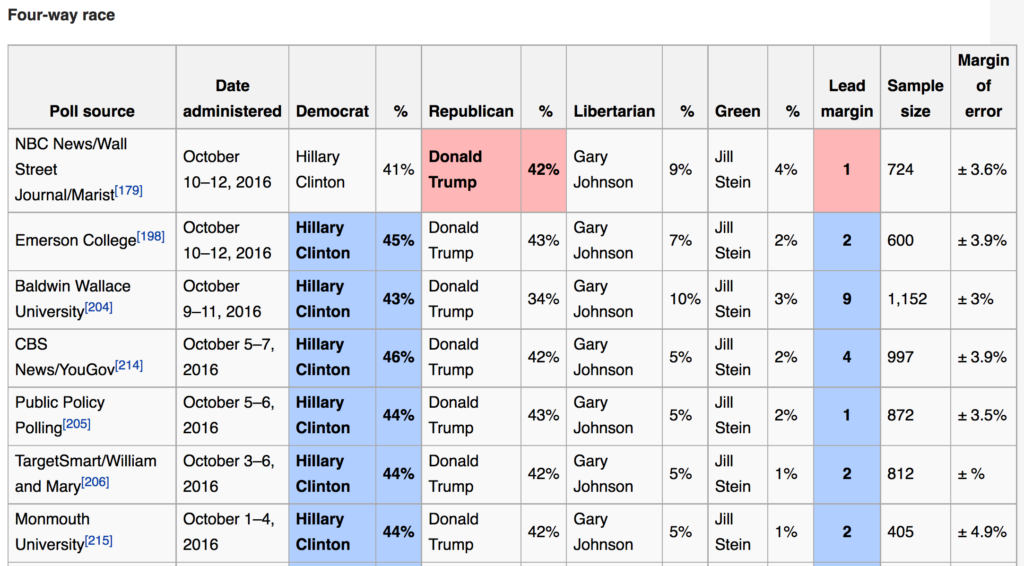

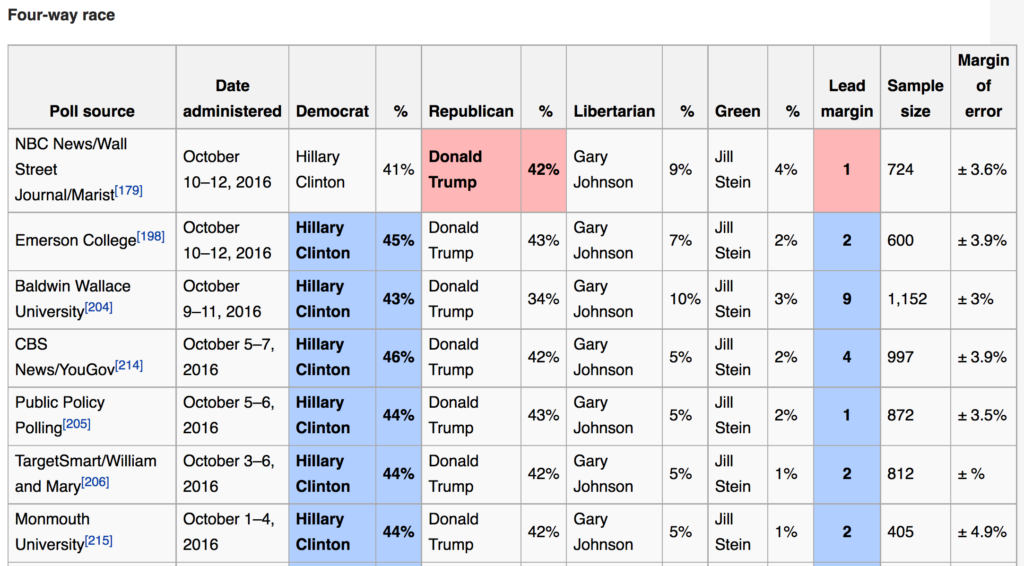

Now let’s take a look at some of Ohio’s recent 4-way polls:

According to my back of the envelope calculations, the combined Johnson and Stein margins are anywhere from 1.4 times (the Baldwin Wallace poll) to 13 times (the NBC News/Wall Street Journal/Marist poll) the margin of difference between Trump and Clinton. This means that if even a small number of third-party voters switched their allegiance to Clinton, it would make her election far more of a sure thing than the extremely tight race depicted above. By choosing to stick with third-party candidates, these voters are effectively withholding a contribution to the only collective action that can prevent a Donald Trump presidency – a vote for Hillary Clinton. Until we have an alternative voting method like instant-runoff voting or proportional voting, a third-party vote, especially in an extremely competitive state like Ohio, is an individual contribution to a collective action that signals “I am OK with the possibility of a Trump presidency.”

Let’s return to the second set of risks when you choose to sit out voting for president, or voting third-party: that the risks of your actions won’t bring about something far worse than you could have imagined. As outlined above, I assume that those voting third-party or sitting this out are indicating by their actions that “both sides are as bad as the other” and that therefore, they truly believe the actual presidencies of each candidate would be indistinguishable. Going back to the vaccination metaphor and herd immunity (which protects those who cannot be immunized), what does this mean for those who cannot vote?

In the American electorate, there are three large populations that are disenfranchised from voting in federal elections. These include children, non-US citizens, and depending on the state, those currently incarcerated or with a felony conviction. Since childhood is a much more straightforward trajectory than citizenship or carceral status, this is why some political scientists distinguish between voting-age population and voting-eligible population.

Many voters in the 2016 general election appear to have become so disgusted by the idea of “voting for two terrible candidates” or “always having to vote for the lesser of two evils” that they plan to vote third-party, or forego voting altogether to register their dissatisfaction. But if we accept the reality that only one of two candidates (Clinton or Trump) will win the election on November 8, we have a moral imperative to select for the least amount of harm for the greatest number of people. I firmly believe that a Trump presidency would be far more devastating for those who are shut out of voting, and therefore the only moral choice is to set aside my political differences with Clinton and vote for her.

Let’s look at this through the lens of climate change. Children have no voice in this election, and yet the actions that the United States takes – or doesn’t take – on climate change in the next few years could make the difference between a grim but adaptable future, and complete horror. These changes are already taking place, and will only accelerate by the time today’s children become part of the voting-eligible population and can legally vote their intent. Until then, we have a moral obligation to ensure that one of only two possible scenarios (Clinton or Trump) is the one that will inflict less damage than the other alternative. Clinton is nowhere near as visionary as she should be on climate change, however she accepts that it is a reality the US must address in cooperation with the rest of the world. Trump, on the other hand, believes that it is a fiction. Which viewpoint has the greater danger of harm for those who cannot currently cast their own vote?

If you truly cannot abide the idea of a Trump presidency, if the idea of Trump governing the United States fills you with horror, then there is only one rational choice you can make if you have voting rights: to vote for Hillary Clinton. Because if you can’t countenance a Trump presidency but you rely on other people to cast the ballot for Clinton you somehow aren’t willing to commit yourself to, you are contributing to a free rider problem: you want to vote your conscience, and let other people do the work of making sure Trump gets nowhere near the levers of power. Which then begs the question: how can you be sure that there aren’t too many others operating on the same mindset as yourself, which could then give Trump the number of votes he needs to be first past the post? Like anti-vaxxers who suddenly find their own children getting measles because too many other parents made the choice not to contribute to herd immunity, those who sit out or cast a third-party vote while fearing a Trump presidency are putting their own interests over the collective good of all.

Perhaps as a voter, you truly believe both a Clinton and Trump presidency would be equally reprehensible. You’re OK with either outcome. You’re willing to roll those dice. In that case, let me reframe the moral question as, “Who would you rather have as your political enemy?” In one of the smartest political commentaries I’ve yet seen on this totally appalling election, British writer Laurie Penny explored this exact question:

I do not expect a president of the United States —or any government leader, for that matter — to be radical. It is not capitulation to be realistic about what can be achieved at the ballot box in a modern democracy, particularly in a presidential election. It is not defeatist to understand that the very most you can hope for is to stop things getting worse as fast as they might otherwise have done. […]

A general election is about nothing more or less than choosing your enemy. Any government leader must be considered an enemy to those who believe in radical change. Hillary Clinton is not yet that enemy but by damn. I hope she gets to be. Hillary Clinton is the sort of enemy I’ve been dreaming of over ten years of political work. She’s the kind of enemy you can respect. I look forward to fighting her on her commitment to climate protection, on workers’ rights, on welfare, on foreign policy. Bring that shit on. That’s the sort of fight I relish. I want to argue over how the state can best serve the interests of women and minorities, not whether it should. That’s the sort of fight that makes me better. Four more years of fighting Donald Trump and his foaming acolytes would demean everyone involved.

My values are such that even though I disagree with Clinton on much, as a politician she is still playing by the same basic principles I expect from a President of the United States: to seek specialist knowledge from diverse experts, to wholly reject exploitation of racial, ethnic, and religious grievances for political gain, and to have previous experience on which to draw. On all of those counts, Donald Trump is an utter and spectacular failure. He routinely rejects the advice of specialists on domestic and foreign affairs. He exploits racial, ethnic, and religious grievances to an alarming degree. Finally, a person who has never served a day in public service, whether political, civil or military, is unfit to become a head of state, which requires an entirely different set of skills from running a for-profit entity.

Every day, normal people suck it up, grit their teeth, and roll up their sleeves for a vaccine. They might not like it, it might hurt for a while, but in the grand scheme of things, they are contributing to collective action that ensures the general well-being of those around us. If you are undecided, thinking about staying home, voting third-party, or a Republican who is leaning towards Trump even if he makes you sick to your stomach, on the eve of this election, I implore you to contribute to our electoral herd immunity. Suck it up, grit your teeth, and vote for Clinton for the general well-being of those around us.

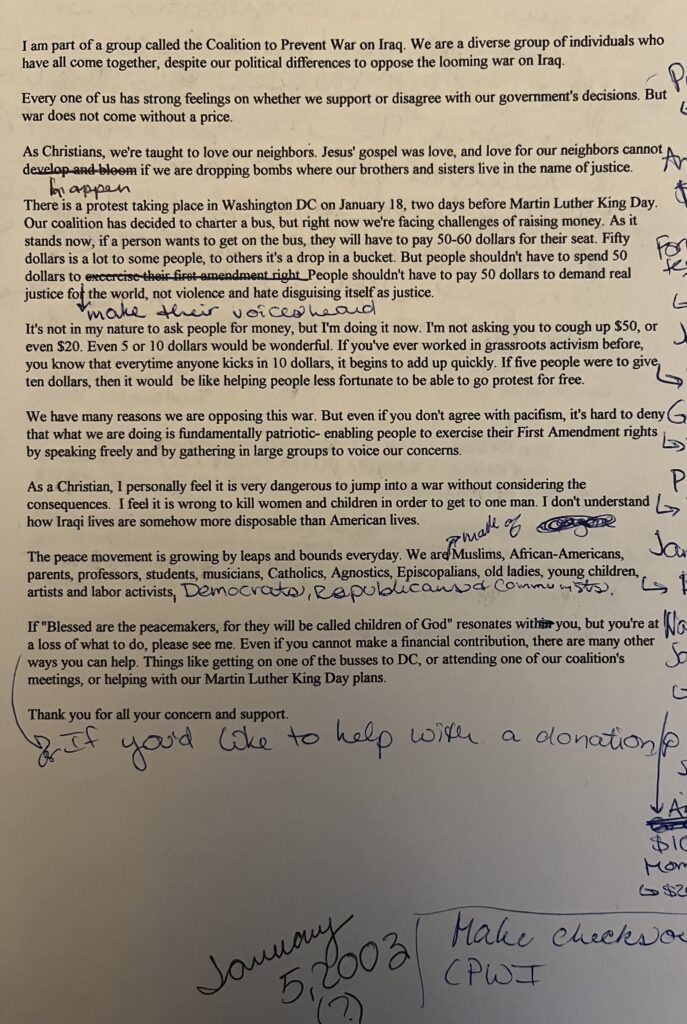

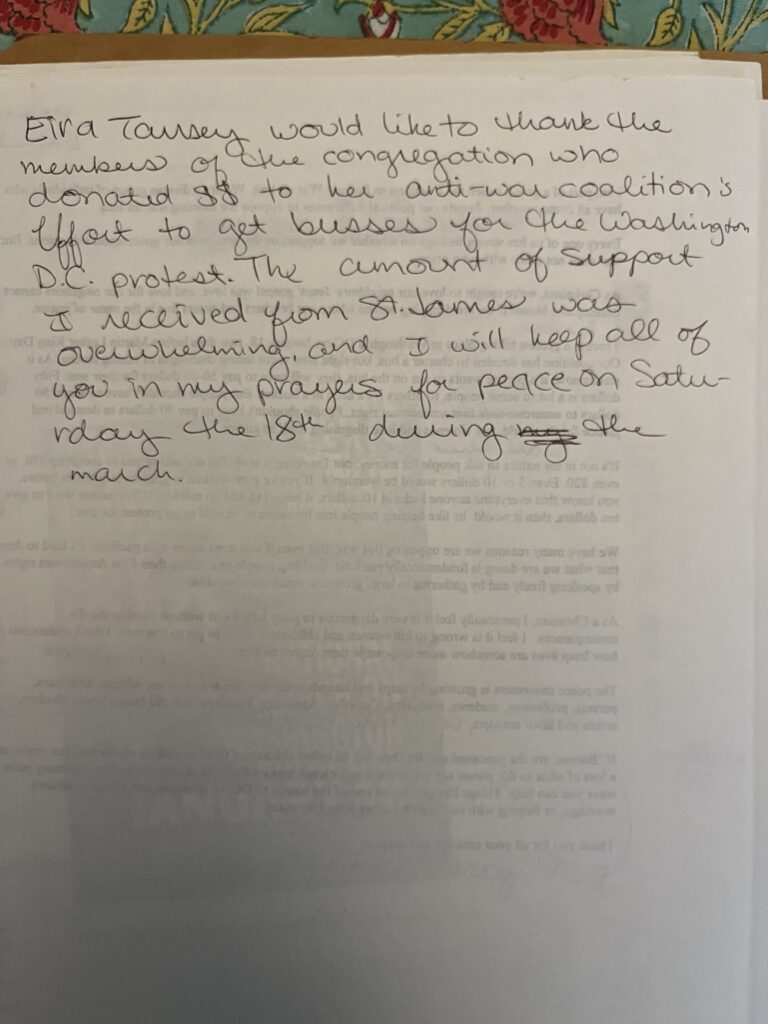

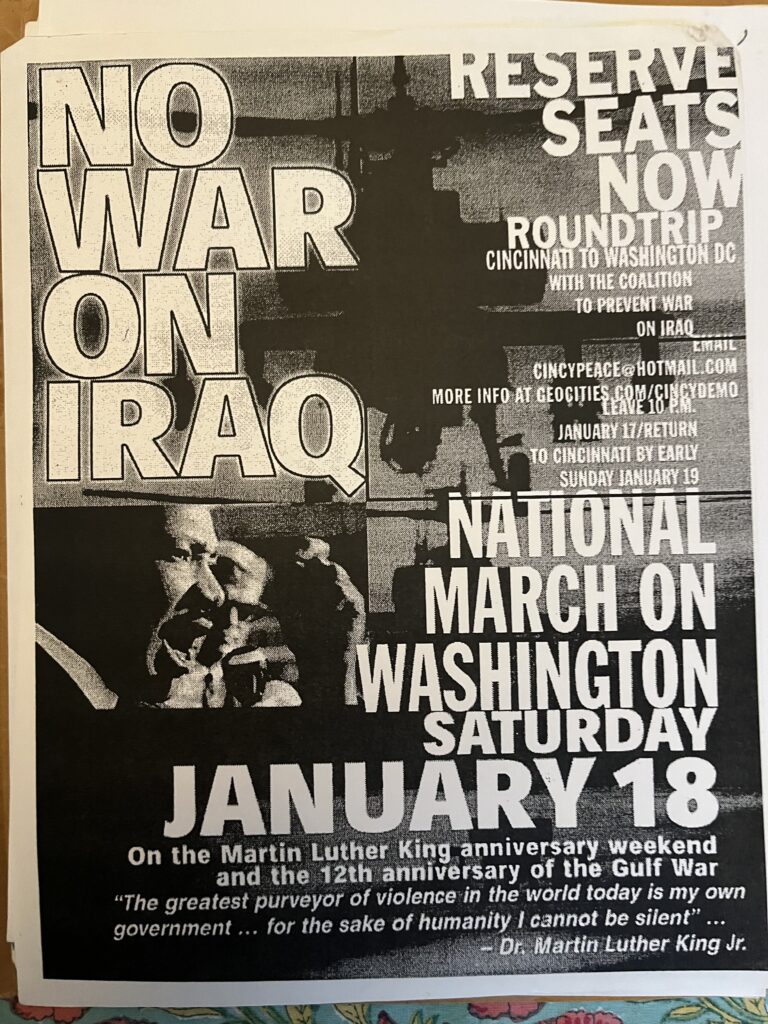

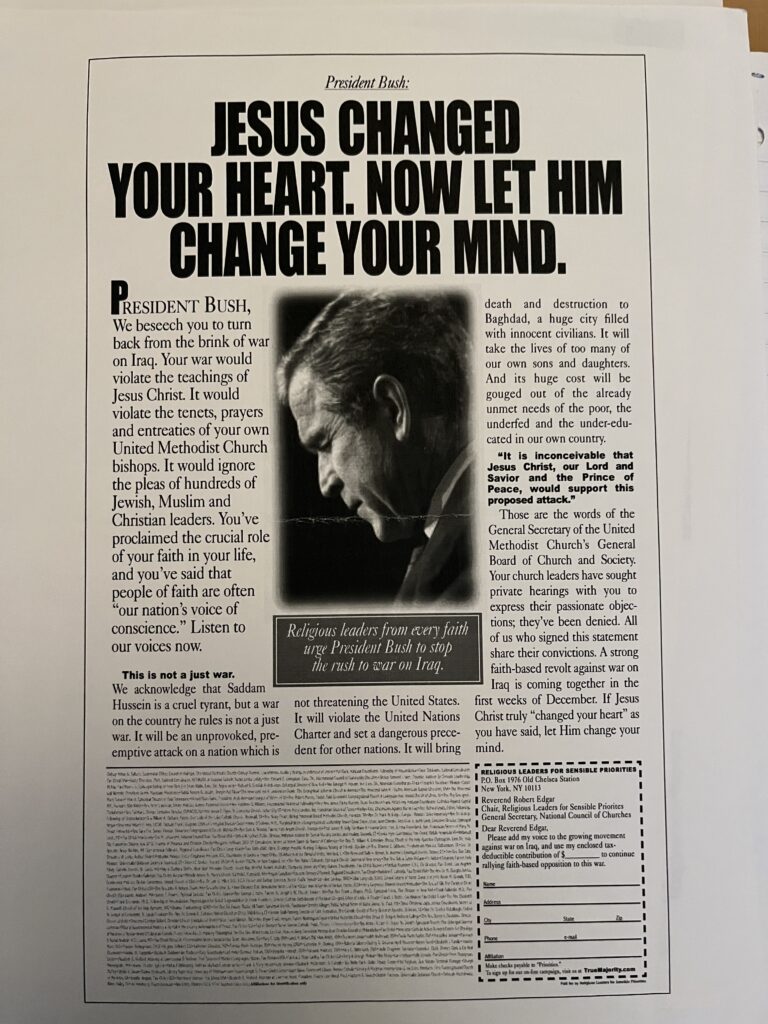

[1] To me, these drawbacks are the standard left-wing criticisms of Clinton. She is too cozy with the wealthy, her climate change proposals are not nearly aggressive enough for what we should have started doing 20 years ago, her record on fracking is not good, and as someone whose job involves public records issues, the private server email business is totally appalling. Finally, my baptism into leftist politics was through protesting the invasion of Iraq in 2003, before I could even vote. If I knew Colin Powell was lying to the UN as a teenager, if I managed to get my slightly conservative Episcopalian church to help fund me to go protest in DC, there is still a part of me that can never quite move on from the fact that Clinton authorized the use of military force in one of the worst follies that has ever taken the lives of thousands of American servicemen and women, and countless lives of Iraqis. All this said, and despite my misgivings, I am early-voting for Clinton soon and even volunteering here and there for her campaign when I have a free hour in my schedule. The alternative of a Trump presidency is simply too horrifying to contemplate.

[2] And it goes without saying, but whose encouragement of his supporters to express and act on similarly bigoted views is beyond the pale.

[3] To be clear, every election is important, and local and state elections often affect your daily life as much, or if not more, than presidential elections. Failure to recognize this on the broad part of the electorate (and the get out the vote efforts of liberal/left political infrastructure) is how we have ended up with Republican-dominated governorships and state legislatures across the United States.

[4] To give credit where it’s due, the herd immunity parallel has popped up a couple times in the epic MetaFilter election threads. I think this might have been the comment that originally lit up this light bulb for me.

1 Comment