This is an annotated version of the lectern copy of my opening keynote at NDSA’s Digital Preservation 2017: Preservation is Political in Pittsburgh on October 25. You can watch the recording here.

There is something I didn’t tell people in my formal talk, but I want to share here. Prior to my keynote, the last time I was in Pittsburgh was when I drove up the day after last year’s presidential election (after having worked the entire day as a poll worker in a Cincinnati suburb), because I was on an environmental panel for the Association of Moving Image Archivists annual meeting that was being held in downtown Pittsburgh. During our AMIA panel, everyone said, “Well I did all my preparation a few days ago, who knows what will happen to the EPA or Paris agreement now?” So it felt like things really came full circle for me to be asked back to Pittsburgh, a city that I love and a city that has such strong environmental and cultural ties to my beloved hometown of Cincinnati, but the site where, among archivists, I processed much of my immediate post-election grief and shock. And so it was a profound and moving experience to return to the same location, a year later, to speak in such a public way about one of the topics nearest to my heart. I am so grateful to the NDSA/DLF organizers for that opportunity.

When I wrote this keynote, there was a lot I left on the cutting room floor. Since I am only planning on revising a small part of my keynote for subsequent publication, this is my main opportunity to throw back in those bits as footnotes, and additional thoughts about the weird times we are all living through. The main text is the lectern copy I used during the keynote itself. The images are the slides I presented in Pittsburgh. Following the lectern copy text are a list of sources, and my extra bonus content annotations.

-Eira

THE NECESSARY KNOWLEDGE

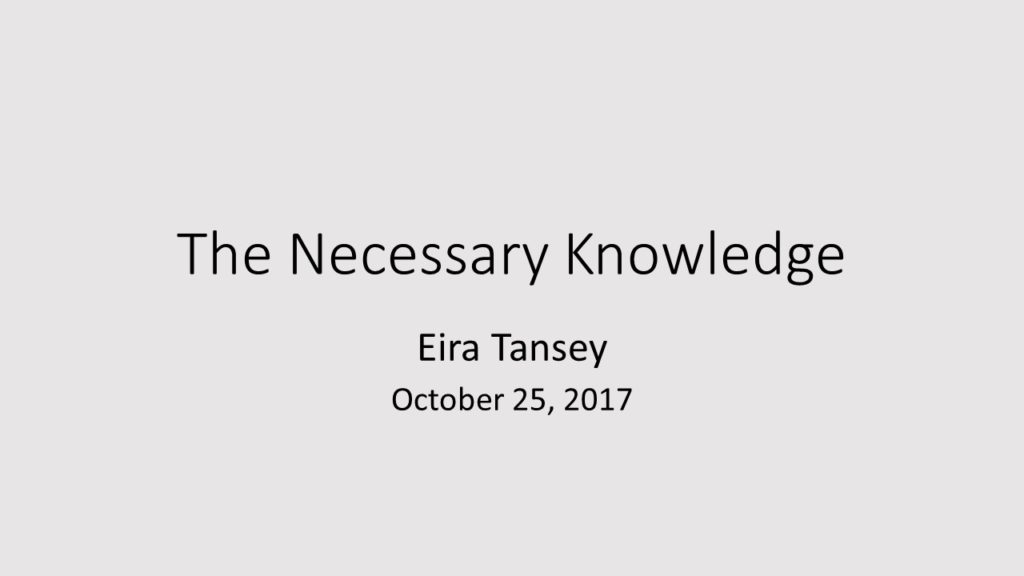

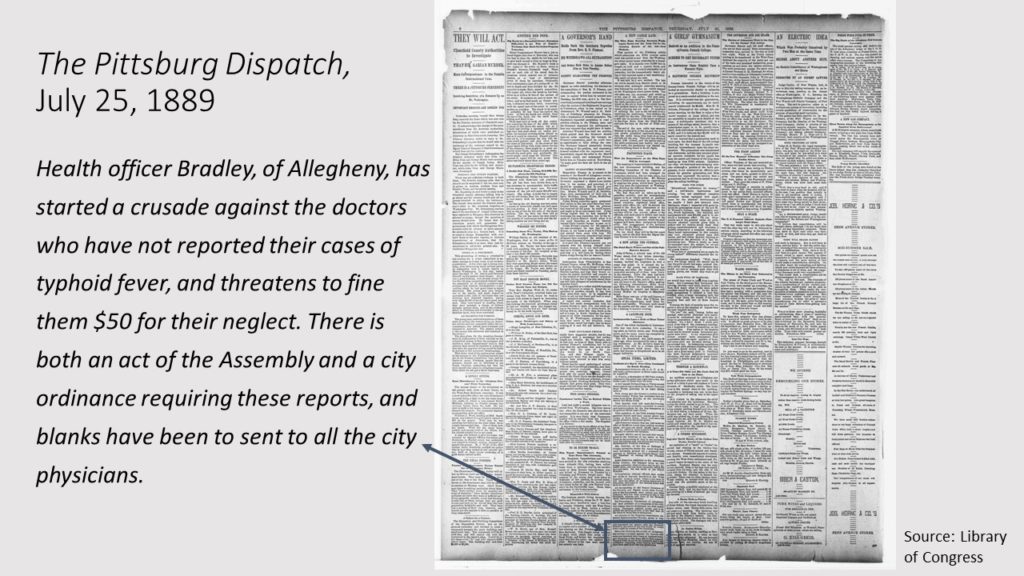

In 1889, an item appeared at the bottom of the Pittsburg Dispatch. Just a few lines long, and sandwiched between reports of train accidents, it read:

Health officer Bradley, of Allegheny, has started a crusade against the doctors who have not reported their cases of typhoid fever, and threatens to fine them $50 for their neglect. There is both an act of the Assembly and a city ordinance requiring these reports, and blanks have been to sent to all the city physicians.

The Act of the Assembly had been in place for years, and it would be expanded as the death tolls rose. Pittsburgh had a disproportionately high number of typhoid cases, and this modest notice foreshadowed the struggles that link environmental protection, public health, and recordkeeping in a way that American society struggles with to this day.

River Pollution

The lack of consistent morbidity reporting by physicians, despite their legal requirement to do so, reflected part of the long transition to government vital record keeping. Record keeping had expanded as government responsibility grew for public health matters. Public health matters were becoming urgent as industrialization and city crowding endangered the health of Pittsburgh’s air and water. As typhoid fever cases accumulated, the requirements regulating reporting and other measures went from half a page of legal guidance, to nine pages of guidance 2 decades later.

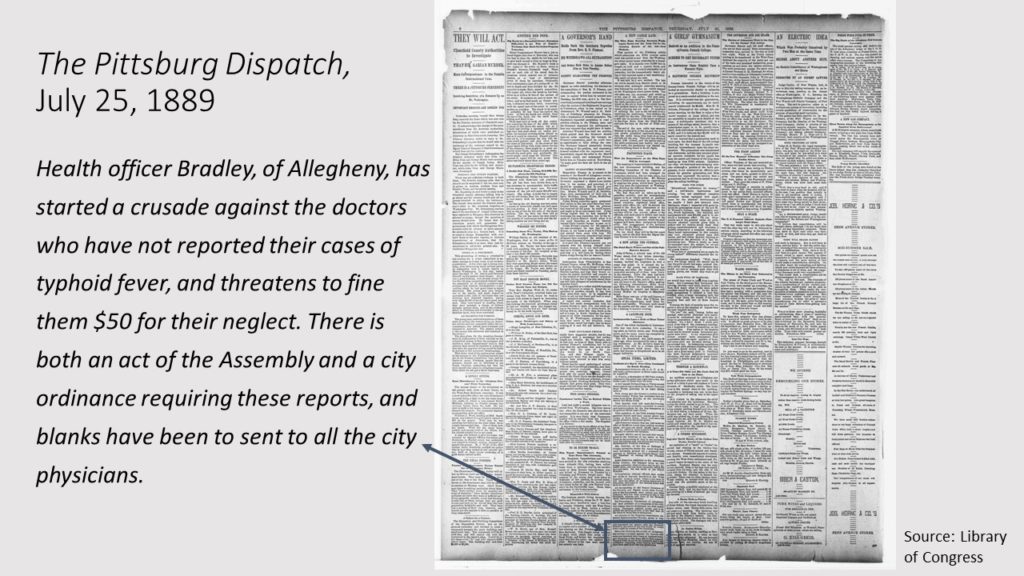

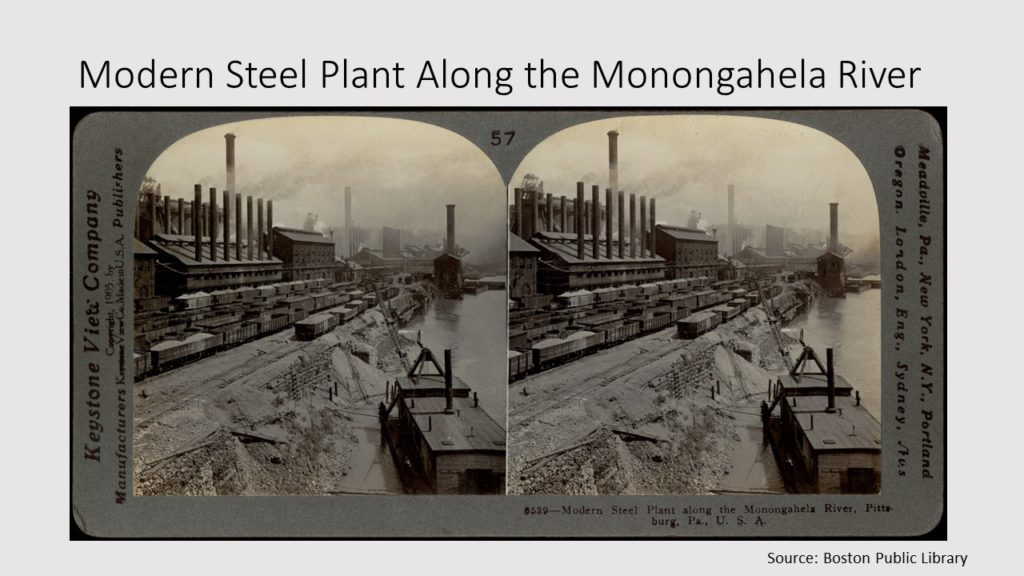

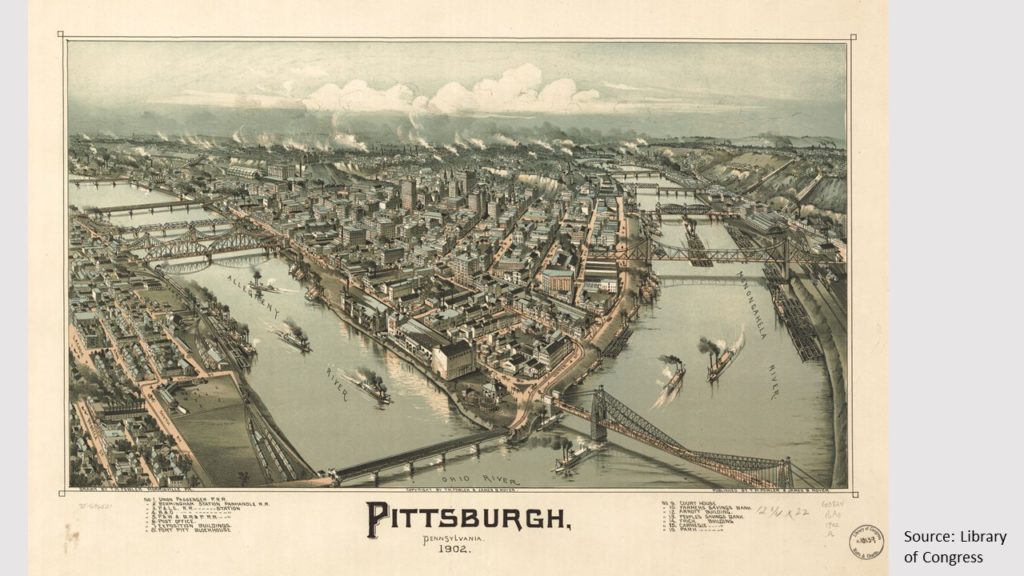

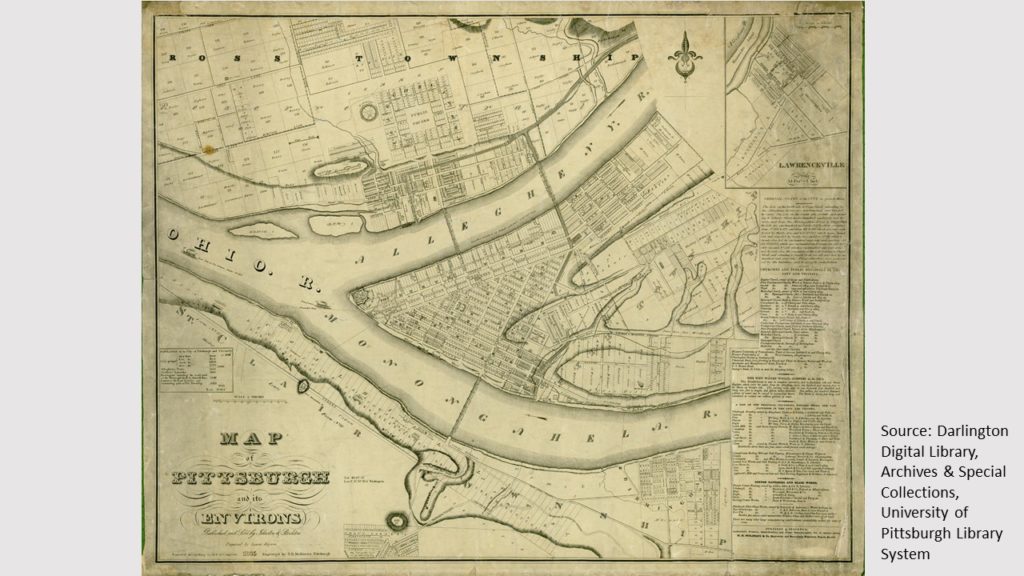

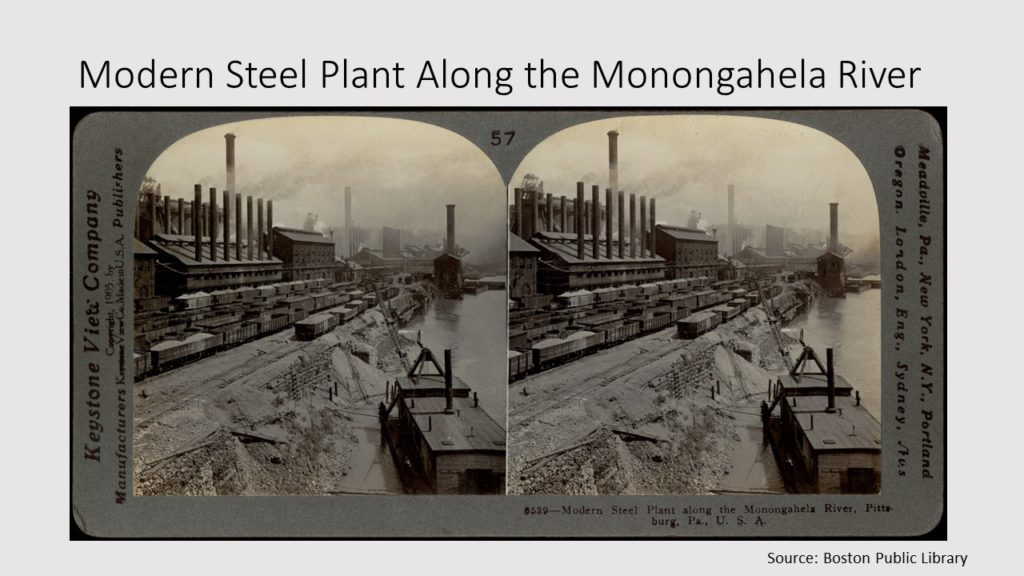

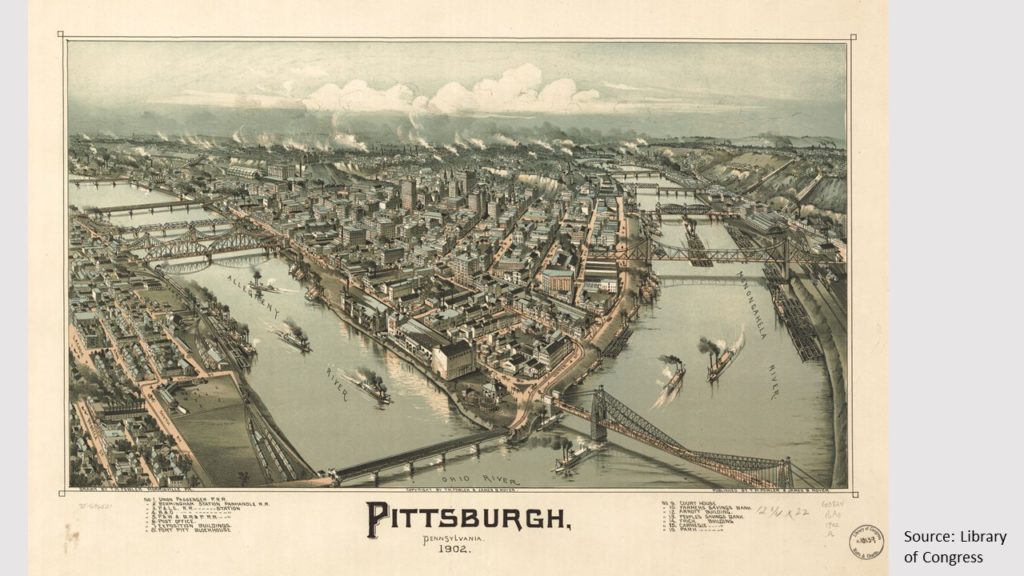

25 years after enough death records were issued, researchers established horrifying links between the health of Pittsburgh’s rivers and the health of those who drank from it. Pittsburgh is bounded by the Allegheny to the north, the Monongahela to the south, and both converge to form the headwaters of the Ohio River. Recordkeeping alone had not reduced the prevalence of typhoid, but it provided clear and convincing evidence that river pollution was to blame for the disease. No one could simply write it off as the fault of squalid tenement living or of tainted milk. The primary culprits were political and corporate leaders who had allowed the rivers to be used as a dumping ground, and neglected to create large-scale water treatment facilities. No one could say exactly how much was dumped in the rivers, but everyone knew that industrial waste of iron and steel mills, tanneries, and slaughterhouses, and the human waste of communities upstream from Pittsburgh, had seriously compromised local water.

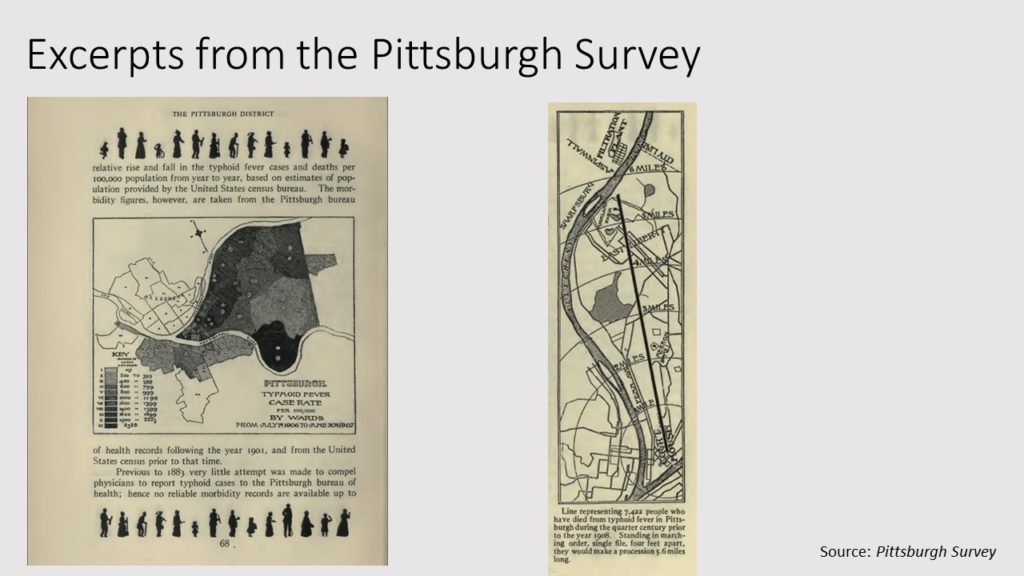

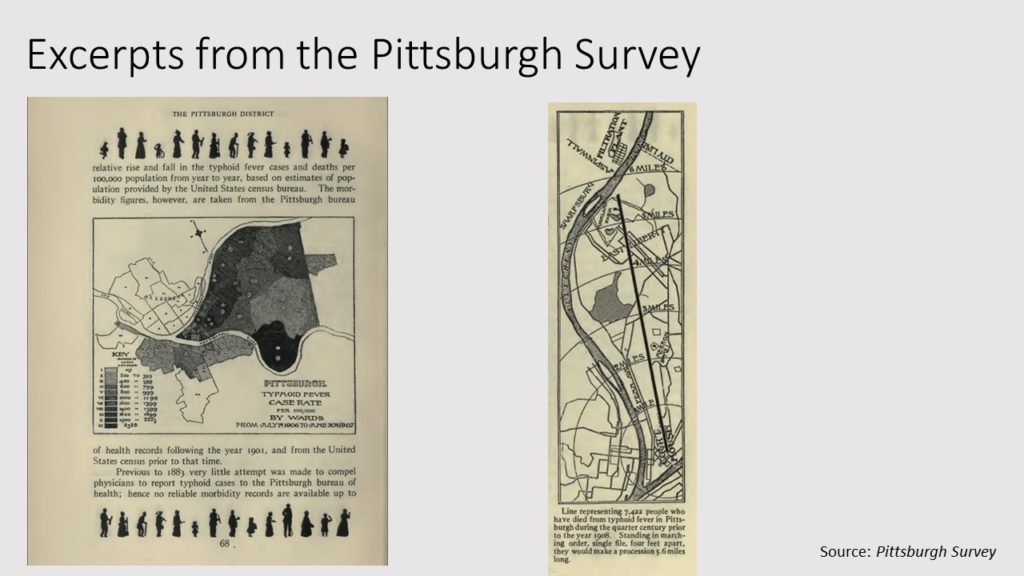

With sufficient death records to establish links between the water supply and typhoid fever, the picture was stark. Pittsburgh had one of the highest typhoid fever death rates in the United States, far higher than any other major city. Reformers pointed to other cities with successful water management systems, where typhoid fever deaths were a fraction of Pittsburgh’s. During a nine-year period following the health commissioner’s threat to fine doctors, the death toll was between 104 and 130 per 100,000 people, while cities like Washington and Philadelphia had close to half this rate (Wing, p. 66). After four years of political delays, during which an additional 1,500 deaths stacked up, Pittsburgh’s water filtration plant finally went into operation.

This assessment was part of a several thousand page study on Pittsburgh at the turn of the century. Carried out by dozens Progressive Era social researchers, the work of the Pittsburgh survey was published in six volumes between 1910 and 1914, and it covered dozens of topics, including women’s working conditions in sweatshops, the status of orphans and foster children, and steel worker unionization after the deadly Homestead Strike.

Pittsburgh, the home of US Steel and the cradle of Andrew Carnegie’s wealth, was a showcase for the fallout of America’s Gilded Age. One of the frequently occurring motifs of the Pittsburgh survey is a city coated in soot, dust, and grime.. This grime was inescapable, from factories where workers were directly exposed, to homes where the dust settled inside the walls. The grime was the inevitable outcome of a city that was the steel capital of the world.

Progressive Era reformers drew explicit connections between the wastes of industrialization and public health in ways that ranged from the graphic exposure of books like The Jungle, to the less-visible work of improving the kind of medical and municipal recordkeeping that we now take for granted. Bureaucratized recordkeeping, such as death certificates, were increasingly widespread by the Progressive Era thanks to advances in increased literacy, the emergence of professions, and the role of the state in controlling public health. However, early recordkeeping was inconsistent, presenting issues for researchers. The Pittsburgh surveyors reported challenges accessing and making sense of municipal and corporate records. Surveyors researching workplace injuries relied on coroner’s and hospital records, as only some employers were willing to share their records. Even then, available records omitted pertinent information, or were illegible. Others investigating public sanitation records noted that while violations were often recorded, prosecutions were rarely initiated.

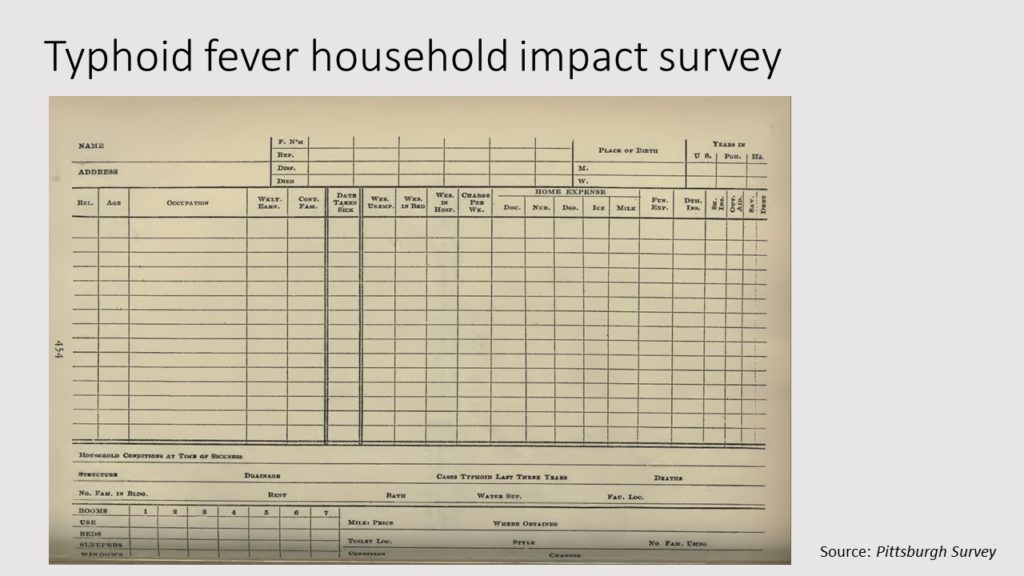

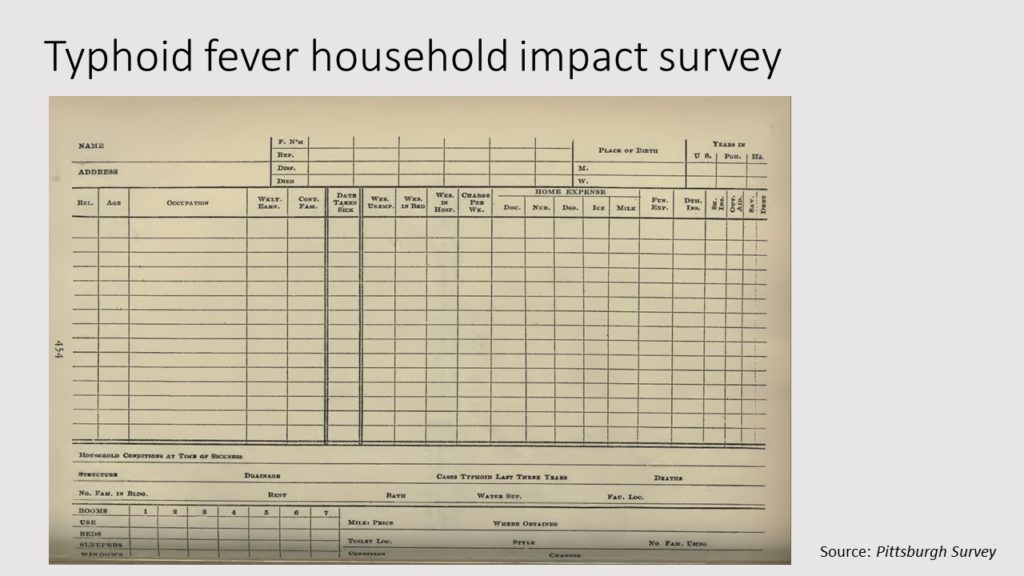

The typhoid surveyors didn’t just draw on death records to establish links between the city’s water supply and typhoid fever, they also created their own records as part of a case study assessing the disease’s economic impact to over 300 families. This work was carried out under the charge of a local settlement house nurse named Anna Heldman, whose existing relationships with local families was viewed as a critical asset for data collection (Wing, pp. 72-74). The surveyors found that there were significant income losses due to sickness from the contaminated rivers. This echoed a problem we continue to struggle with, which is that environmental pollution disproportionately impacts poor communities.

But perhaps what the typhoid fever investigators did best was making records visible in ways that humanized the blandness of statistics. An exhibit of some of the survey’s findings were exhibited at the Carnegie Institute, and the walls featured a frieze depicting over 600 silhouettes of men, women, and children. These represented the area’s typhoid fever death toll from the previous year, and the borders of the published report were similarly decorated. To illustrate the entire 25-year long death toll, the surveyors superimposed a line starting at the courthouse and ending near a filtration plant on the Allegheny River. The line represented an end to end body count of more than 7,422 citizens who had lost their life to typhoid fever, or according to their measurements, a death toll equivalent to almost 6 miles long.

DDT

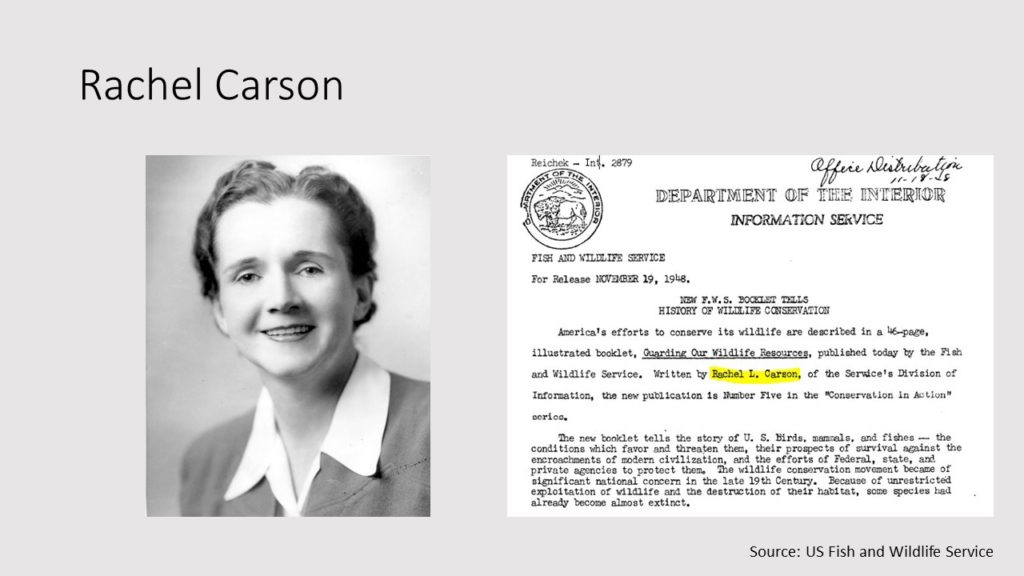

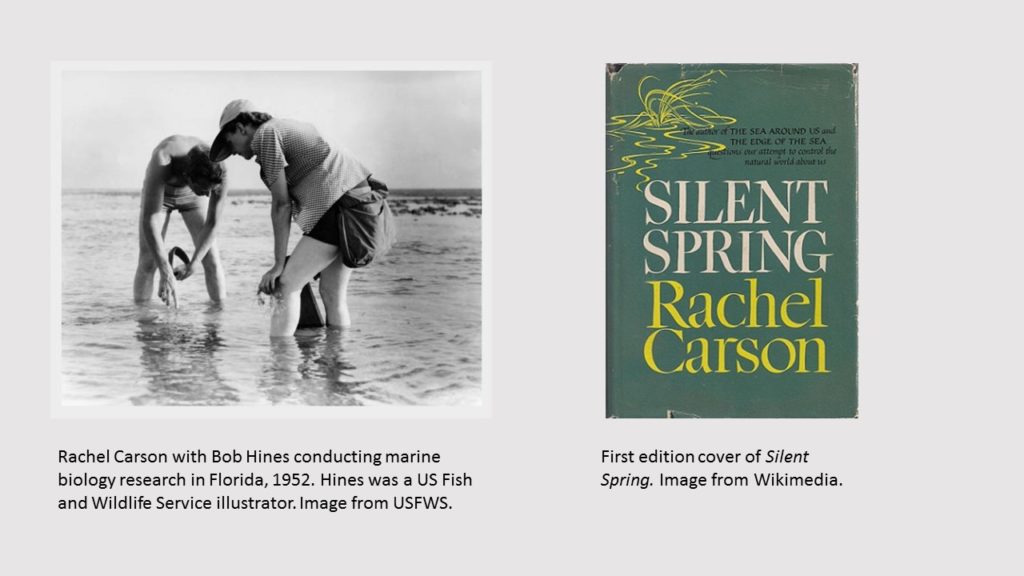

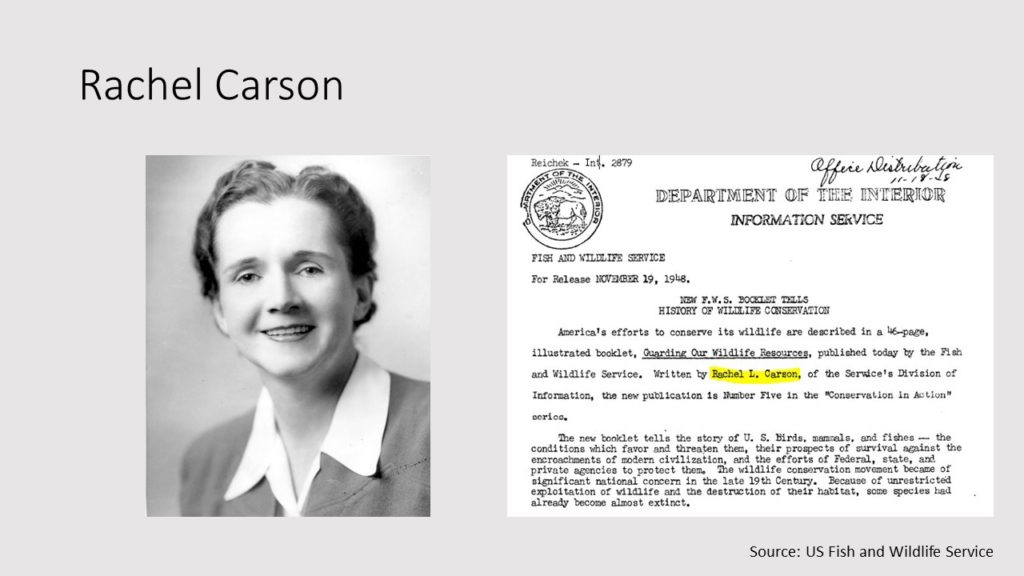

As the field work of the survey started in 1907 (Butler, p. 4), a child was born 14 miles northeast of Pittsburgh (Souder, p.24). She grew up seeing the smokestacks along the Allegheny River, where a century later, a bridge was renamed in her honor on Earth Day. She transformed the US environmental movement through the publication of a book that shook the country and exposed the hubris of unquestioned technology.

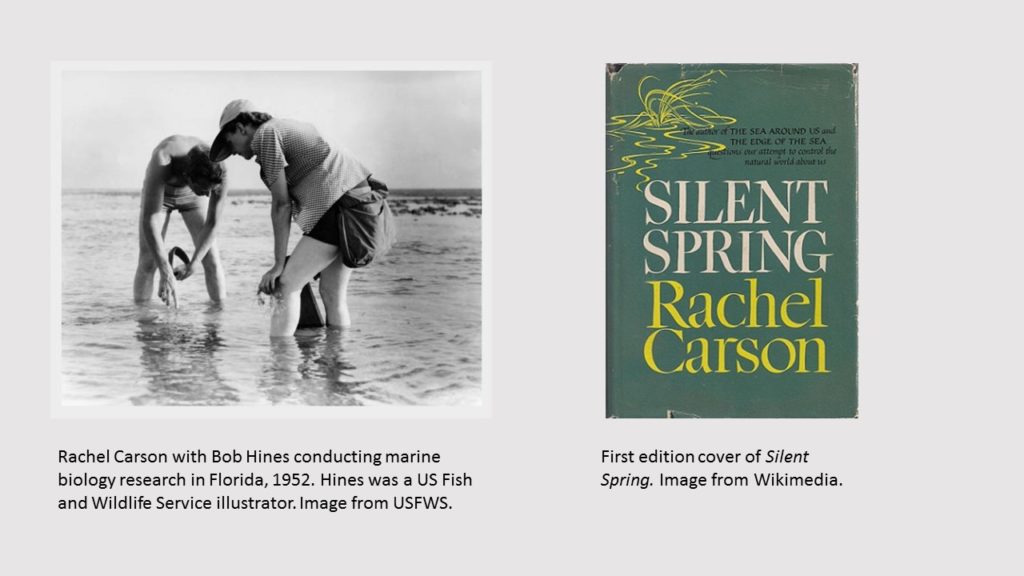

Rachel Carson attended the Pennsylvania College for Women, located in Pittsburgh’s East End, and today known as Chatham University (Souder p.26). She studied biology, and went on to become an information specialist for what eventually became the US Fish and Wildlife Service (Souder, p. 5). There she summarized scientific research into information for the public. Before writing her most famous book, Silent Spring, Rachel Carson publish highly-regarded and wildly popular books about the ocean, making her a household name well before she turned her attention to pesticides.

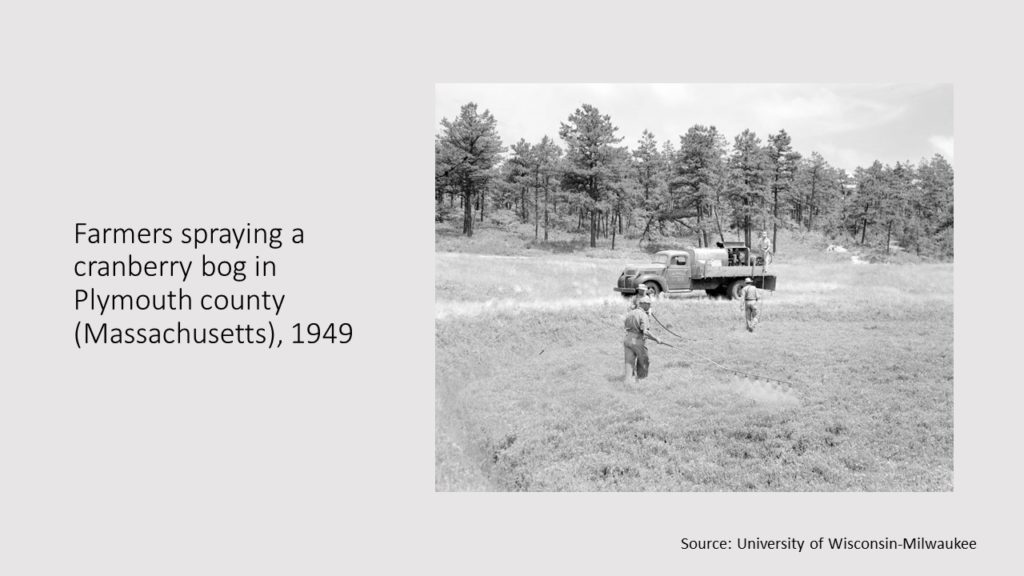

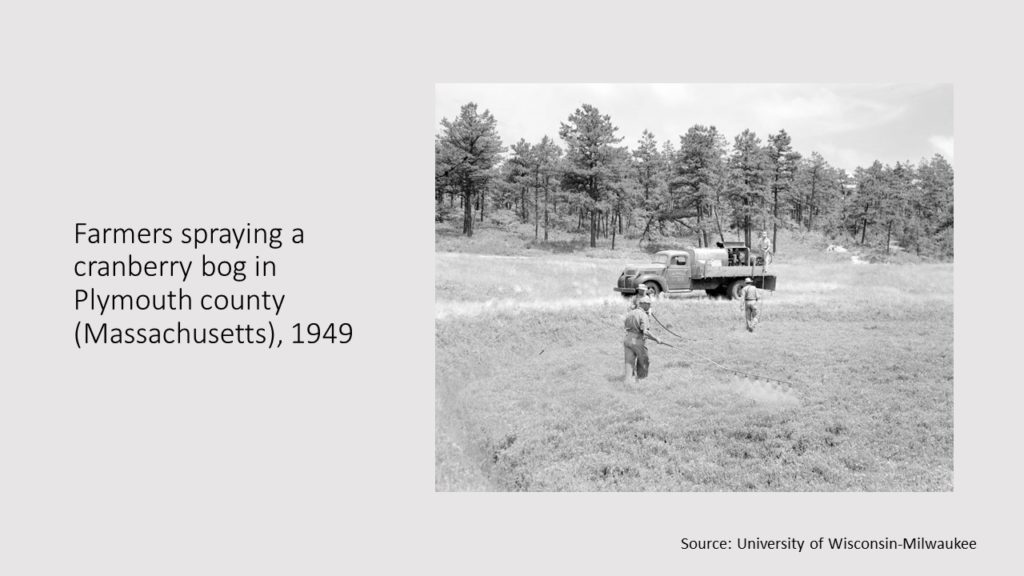

Published in 1962, Silent Spring has been called “a beautiful book about a dreadful topic” (Oreskes & Conway, p. 216). Carson shined a spotlight on the indiscriminate applications of popular post-war insecticides like DDT, which was starting to show up in the food chains of insects, fish, birds, mammals, and eventually within the bodies of humans. A counterweight to corporate boosterism of better living through chemistry, Silent Spring painted a horrifying portrait of lifeless rivers that previously teemed with fish, silenced backyards that used to host busy bird feeders, and agricultural workers who fell in fields. Carson showed that indiscriminate use of pesticides could not be isolated to a single area or species. Chemical toxins accumulated in the bodies of non-target species with profound consequences. A bird might die from DDT or its chemical cousins by eating contaminated worms, by ingesting DDT itself, or by starving to death as the insects it ate were wiped out during a spraying campaign.

Rachel Carson knew about the dangers of widespread pesticide applications for years. As a Fish and Wildlife employee in the late 1940s, she edited reports on the division’s tests of DDT (Souder, pp. 7-8). The main regulatory law affecting pesticide use at the time was the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), but it was primarily a registry and labelling law overseen by the US Department of Agriculture. FIFRA was not expanded to examine toxicity on wildlife and public health until 1972 – the same year that the US banned use of DDT (EPA, “FIFRA” & “DDT”).

To write Silent Spring, Carson relied on her well-honed approaches of pursuing correspondence with field experts, reading staggering amounts of scientific literature, and working closely with librarians. In a nod to the enduring importance of librarians’ labor to her writing, she acknowledged that “every writer of a book based on many diverse facts owes much to the skill and helpfulness of librarians” and specifically thanked Department of Interior librarian Ida Johnston, and National Institute of Health librarian Thelma Robinson for their help. Carson drew on everything from Audubon Club bird watcher reports to Congressional hearings to federal agency reviews to research studies in international journals of medicine.

Carson was not the first person to raise the alarm about the danger of pesticides (Carson, p. 31, 170). But what set Carson apart was her ability to synthesize many bureaucratic reports and scholarly scientific findings into a form that resonated with the public – and compelled regulatory action. She knew that the accusations she lodged against pesticide practices were incendiary, and she took enormous care in documenting all of her claims, insisting that the publisher include a fifty-page guide to her sources. This wasn’t just to ensure scholarly rigor – after all, Silent Spring was a book for a general audience – it was to proactively address the very real concern that Carson and her publisher might be the target of a libel suit.

What happened to Rachel Carson next was a blueprint of attacks that have been replicated against researchers whose findings turn out to be very inconvenient to industries and their government enablers. When Silent Spring was published, corporate interests came for Carson with a viciousness that feels both dated and alarmingly contemporary at the same time. She was castigated for her lack of an advanced degree, her suspicious love of animals, and for being just another hysterical spinster. Carson took care in her measured prose to note that she was not opposed to all pesticide use, but that her opposition was to the unrestrained way in which they were used with scant attention paid to existing safety studies.

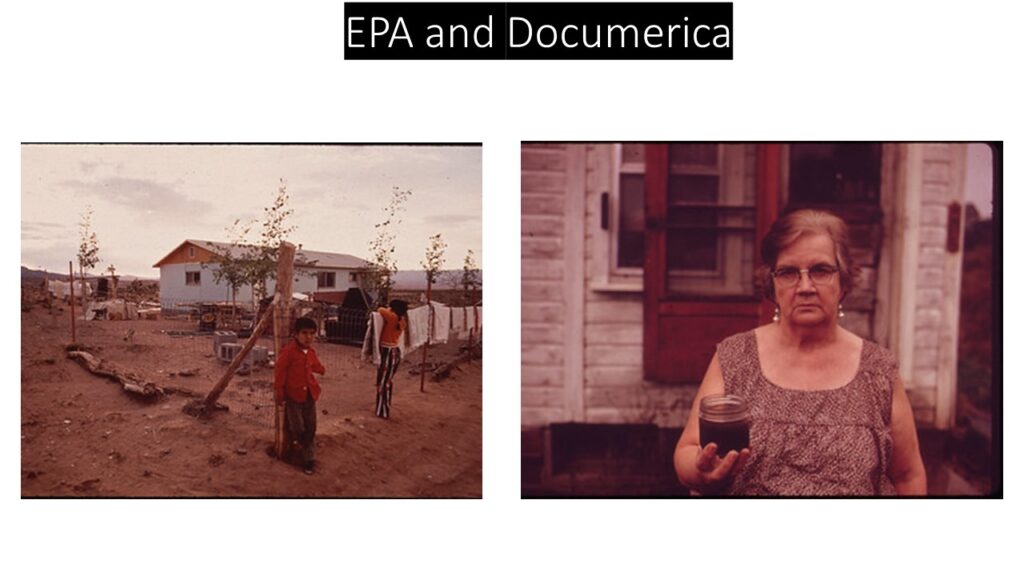

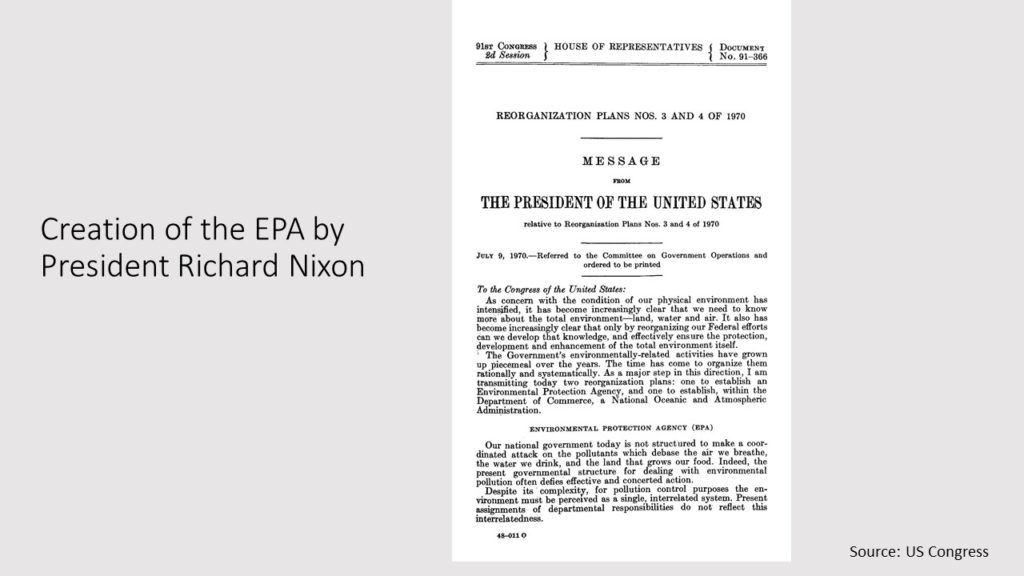

Eight years after Silent Spring was published, Richard Nixon signed a reorganization plan that created the Environmental Protection Agency, consolidating responsibility for dozens of existing environmental laws – including FIFRA – into one agency. Many of these laws were expanded to require significant new record keeping responsibilities to document pollution emissions, and assure citizen’s right to know about potential toxic exposures. The EPA’s original charge included the mandate that it “[gather] information on pollution” to “strengthen environmental protection programs and recommend policy changes.” (Nixon, p. 5). One of the greatest underrated legacies of the EPA’s creation is that it has enormously expanded the amount of environmental information available to the public through monitoring, reporting, and permitting record systems. We do not often think of the creation of records as a victory, but effectively addressing pollution without those records is incredibly difficult, as we can see in today’s Pennsylvania landscape.

Fracking

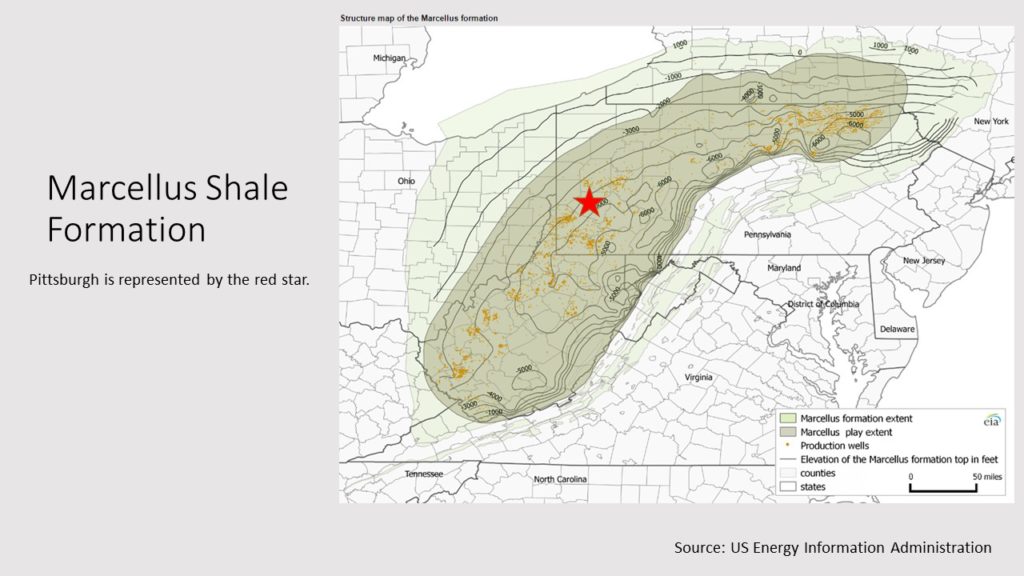

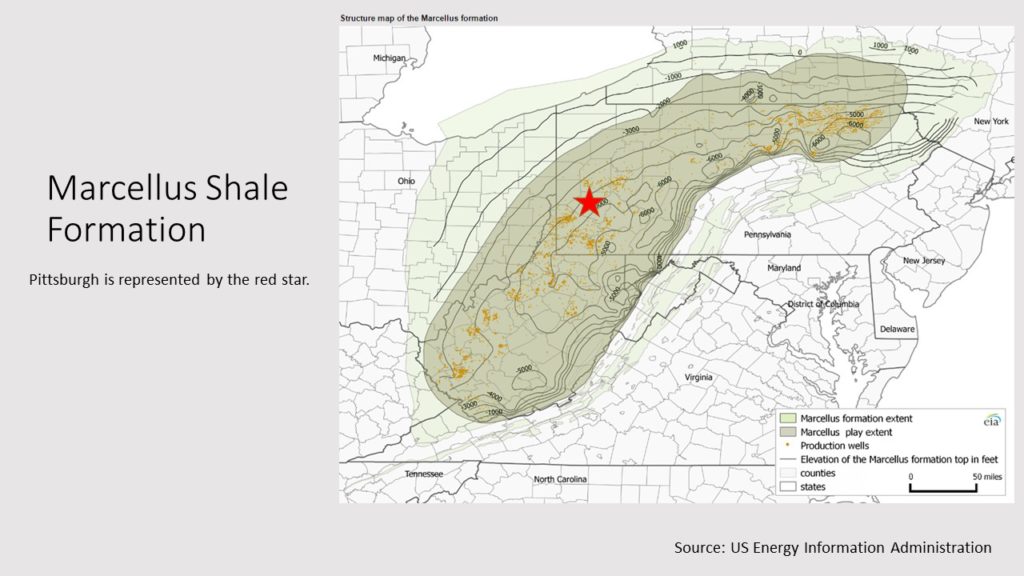

Shortly after President Trump announced he would pull the United States out of the Paris climate agreement, he stated “I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris” (Woodall, 2017). While the city of Pittsburgh has made notable progress towards a fossil free future, it is also in the center of the Marcellus Shale region, the largest U.S. natural gas field and which covers three-fifths of Pennsylvania, as well as parts of Ohio, West Virginia, New York and Maryland (EIA, 2017a). For the last four years, Pennsylvania has been the nation’s second-largest natural gas producer (EIA, 2017b).

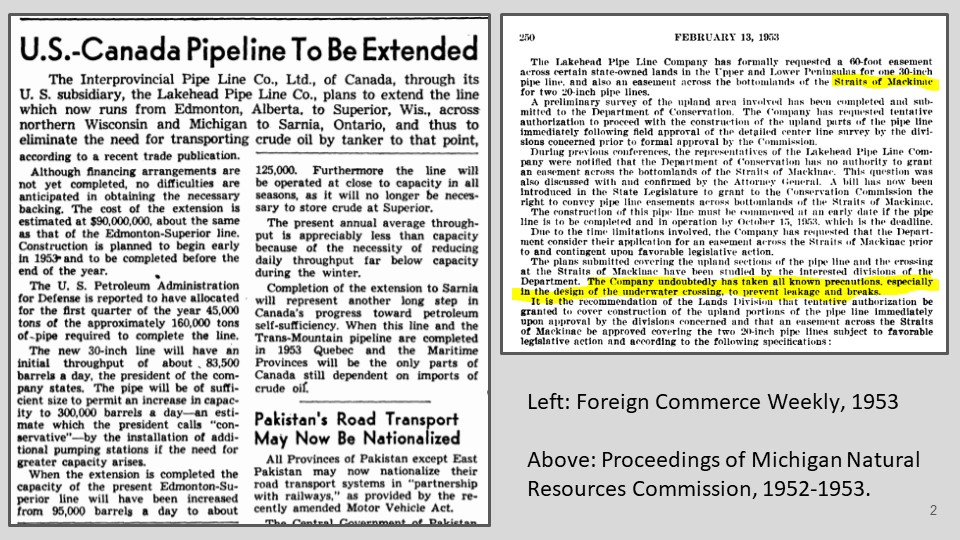

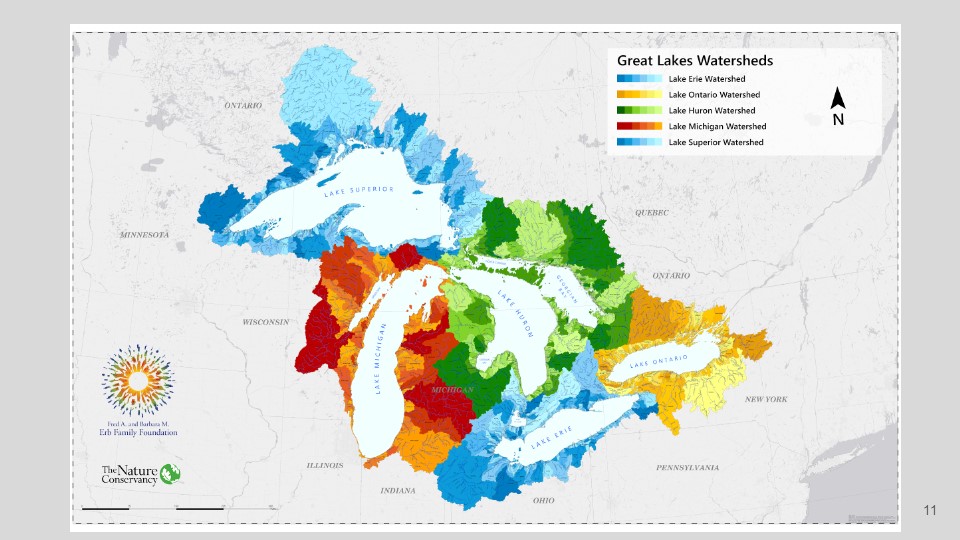

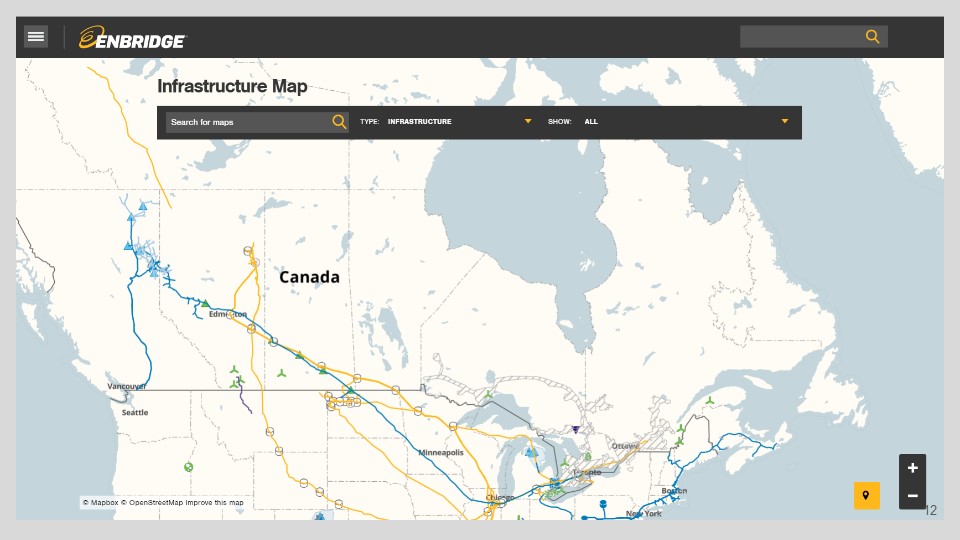

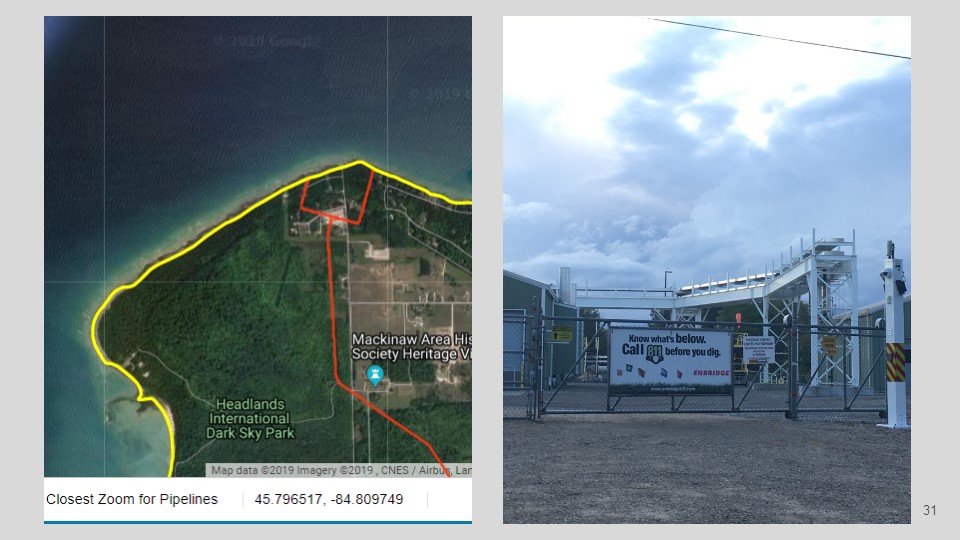

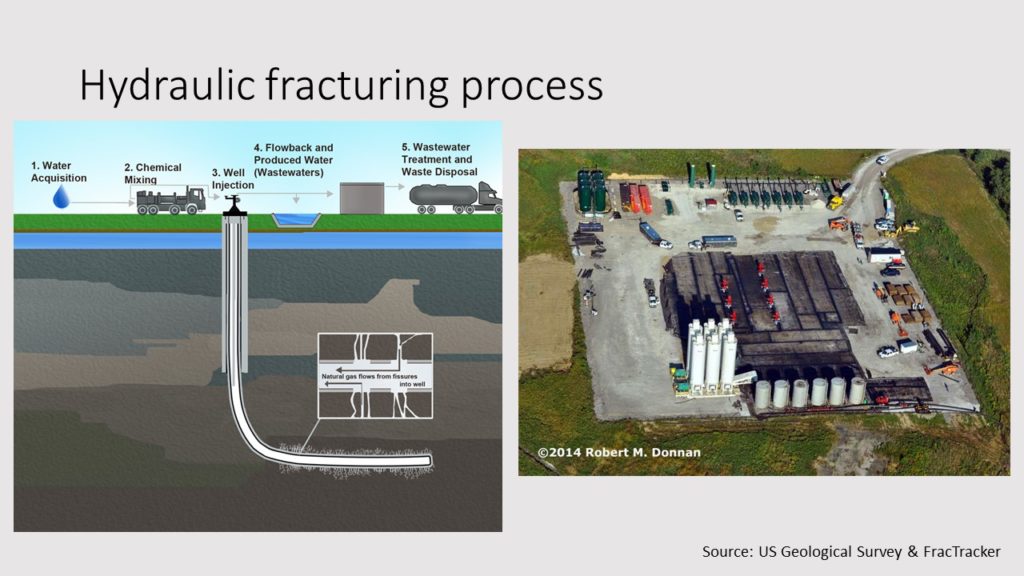

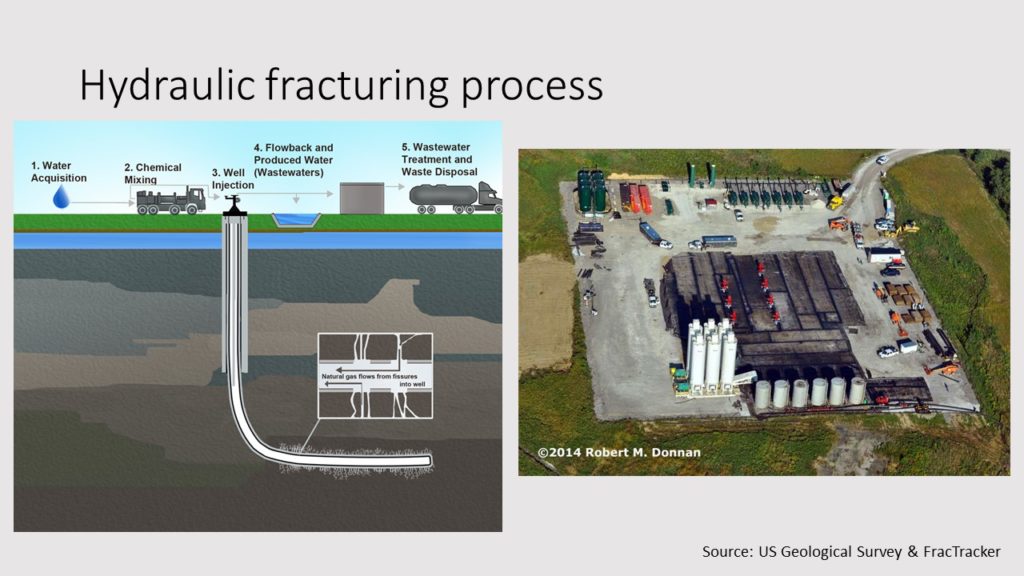

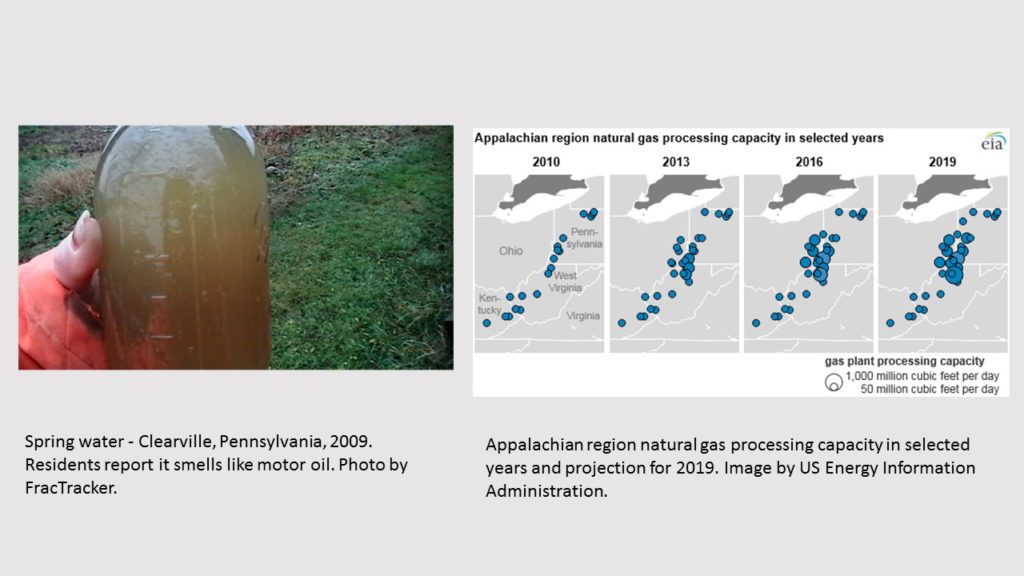

Much of this growth has been due to the expansion of hydraulic fracturing, better known as fracking. Fracking has been around for decades, but it was not widely deployed until the early 2000s (EPA, 2016; Congressional Research Service, 2015a). Fracking is a process where large amounts of water, sand, and chemicals are injected into deep wells to fracture, or crack open, rock formations to release oil and gas deposits. Fracking’s immediate environmental risks come from potential links to earthquakes, methane leakage, and water contamination. Many of the rural residents in the Marcellus Shale region have complained that fracking operations have contaminated their water supplies.

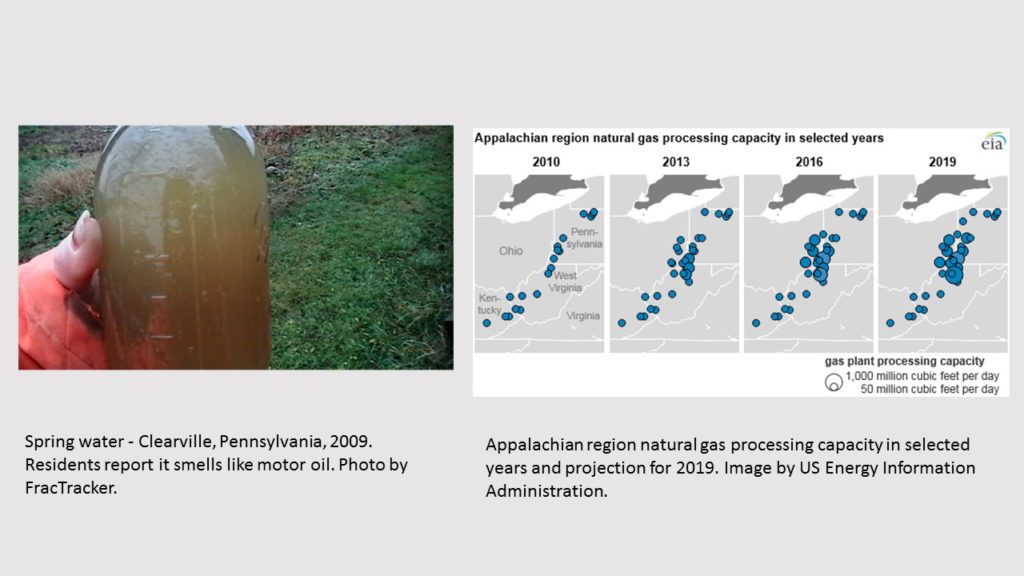

Fracking poses documented danger to water supplies. But establishing a conclusive link to hold energy companies accountable is difficult because of an absence of industry and governmental records . The oil and gas industry claims there is minimal risk, because fracking happens in rock formations below any groundwater supplies. However, there are many other routes to water contamination, including onsite chemical spills, failures in the underground pipes, and improper waste disposal. Contamination of well water, a common water supply in rural regions, is especially difficult to prove because there are often no baseline water purity records prior to fracking. Furthermore, many industries avoid full disclosure of their fracking chemicals by claiming confidential business information (Congressional Research Service, 2015b; EPA, 2016).

Regulation depends on reliable record keeping. Regulations mandate what records will be created in order to ensure health and safety. Industries with potentially serious environmental impact are often not regulated until there is significant public outcry. There is often spotty documentation, at best, on early environmental impacts of new technologies, leaving citizens without the information they need to to prove pollution claims. The problem is worsened by regulatory agencies that struggle with underfunding and an inability or unwillingness to exercise their enforcement powers. It is further compounded by politicians hostile to environmental regulation. These issues can be seen in recent failures of Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection to regulate fracking.

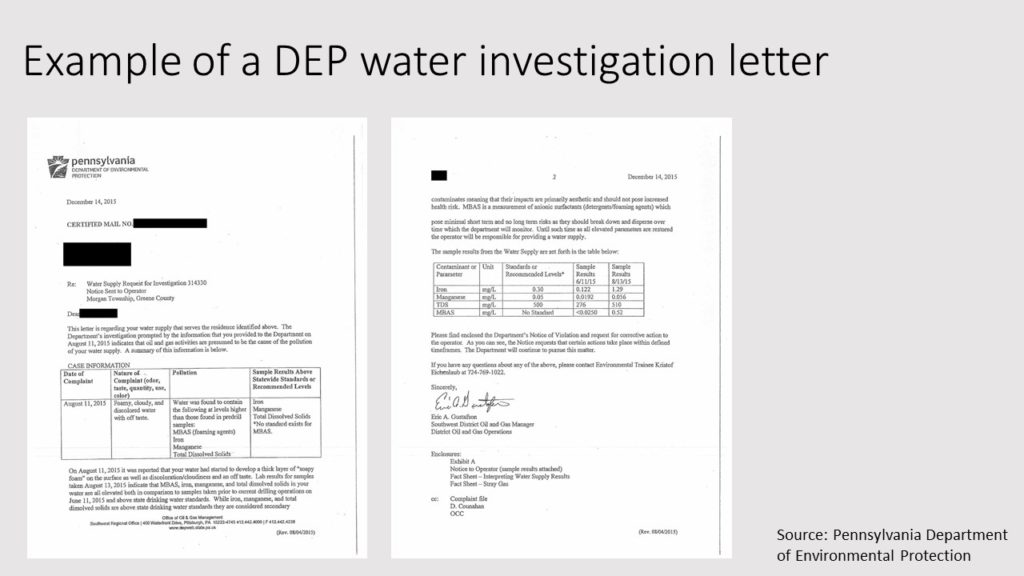

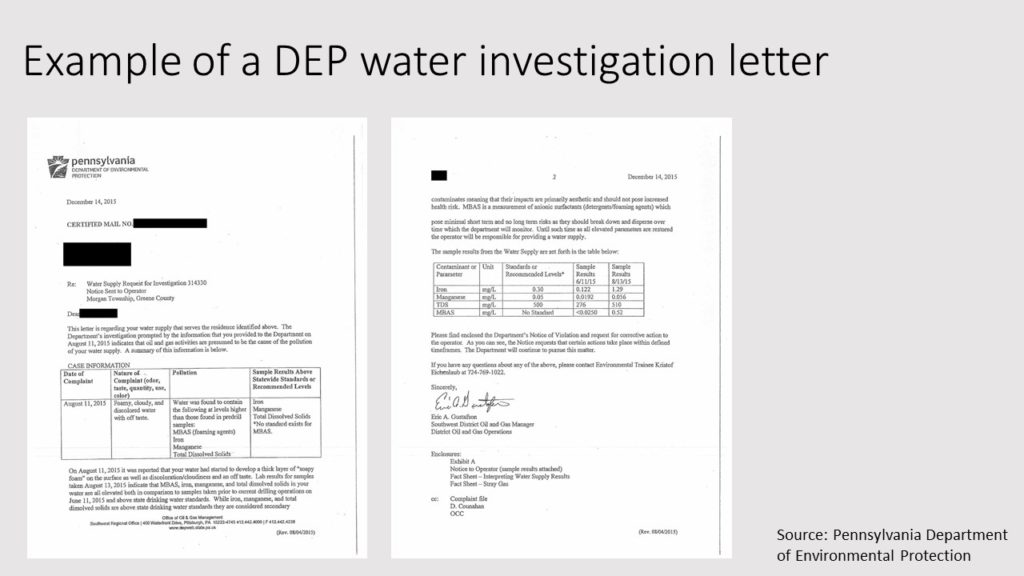

In 2014, the Pennsylvania Auditor General audited the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), reviewing their performance in monitoring and investigating fracking’s effects on water supplies. This is a huge issue because if you think fracking has contaminated your water supply, you have to start by making a complaint to the DEP, which then triggers an investigation. The audit found failure after failure in both DEP’s regulatory responsibilities and its record keeping practices (Pennsylvania Auditor General, 2014). When citizens filed complaints, they did not consistently receive a final letter stating the conclusion of an investigation, inspection records were kept inconsistently, there wasn’t independent verification of industry’s self-reported waste, records were not organized in a way to answer simple big-picture questions such as “How many complaints were related to impacts on water supplies?” and DEP routinely cited confidentiality concerns as an excuse to block access to public records. The Auditor stated he could not conclude whether “public health is being threatened by the gas industry” because “their record keeping is so poor” (Hurdle, 2014). The findings of the state auditor are similar to what much of the scholarly literature on fracking says – that the dangers to water are known, but no one knows quite how widespread it is because state and industry record keeping is so inconsistent. Although the DEP has recently improved some of its online public records access – including crucial citizen complaint records – finding and making sense of the records is notoriously difficult.

Dissatisfied with the status quo, activists have filed numerous public records requests in order to assemble information in a manner far more accessible and comprehensible to the public. The Pittsburgh-based Public Herald literally went to DEP regional offices to scan thousands of citizen complaints which they’ve mapped and made available on their website, publicfiles.org.

Conclusion

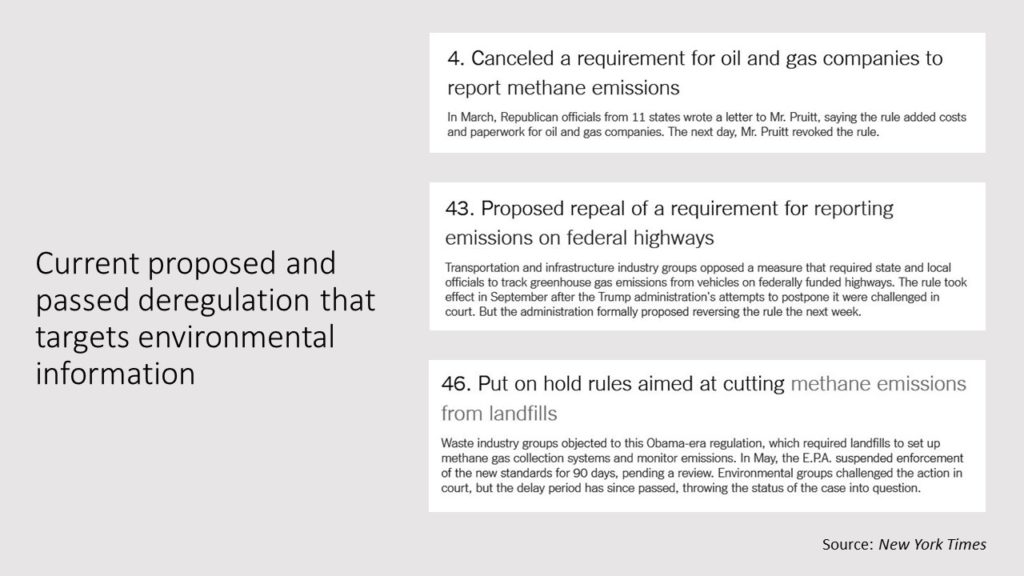

In each of these regional stories, reliable record keeping has been essential to documenting the links between pollution and polluters. When industry and government roll back regulations that require reliable record keeping, we’re quickly on the road to pollution without polluters, in which we know that water and air is being contaminated, but we lack the reliable evidence to document exactly who that polluter is.

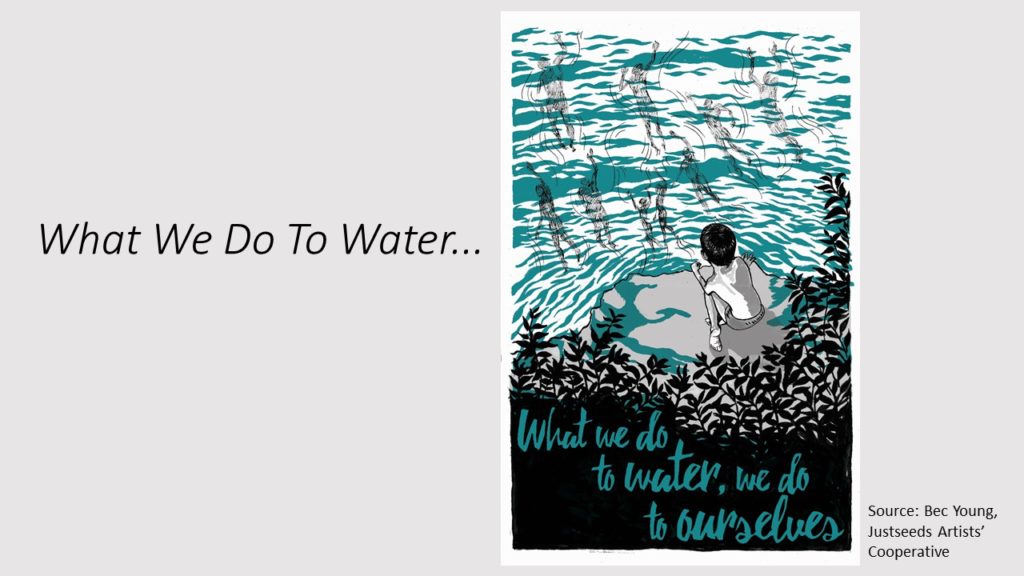

Last year’s keynote by Bergis Jules, was titled “Confronting Our Failure of Care Around the Legacies of Marginalized People in the Archives.” Bergis called for us to “[acknowledge] our willful ignorance around the histories of marginalized people of color and to allow new knowledge to affect how we do our work.” The failure of care is a theme that comes up time and again when one considers how injustices perpetrated against the land, air and water are inseparable from the injustices perpetrated against marginalized peoples. Pollution of air and water disproportionately affects poor communities and communities of color, and yet with all our knowledge about this reality, we have failed to embed the concept of care into the way we approach environmental information and record keeping.

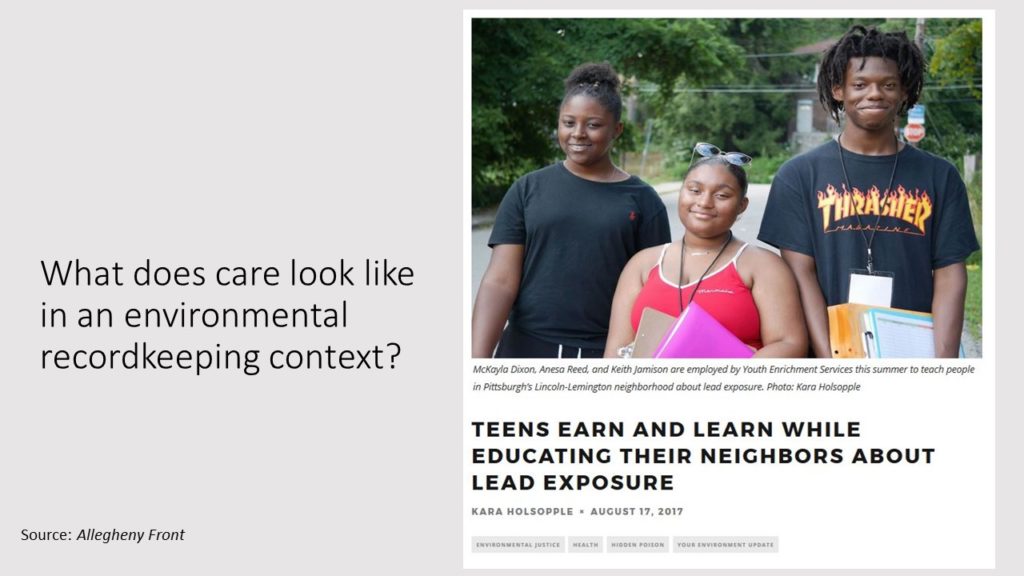

What does care look like in an environmental record keeping context? It looks like record keeping that recognizes that impacts to the environment are inseparable to the impacts on our bodies and communities.

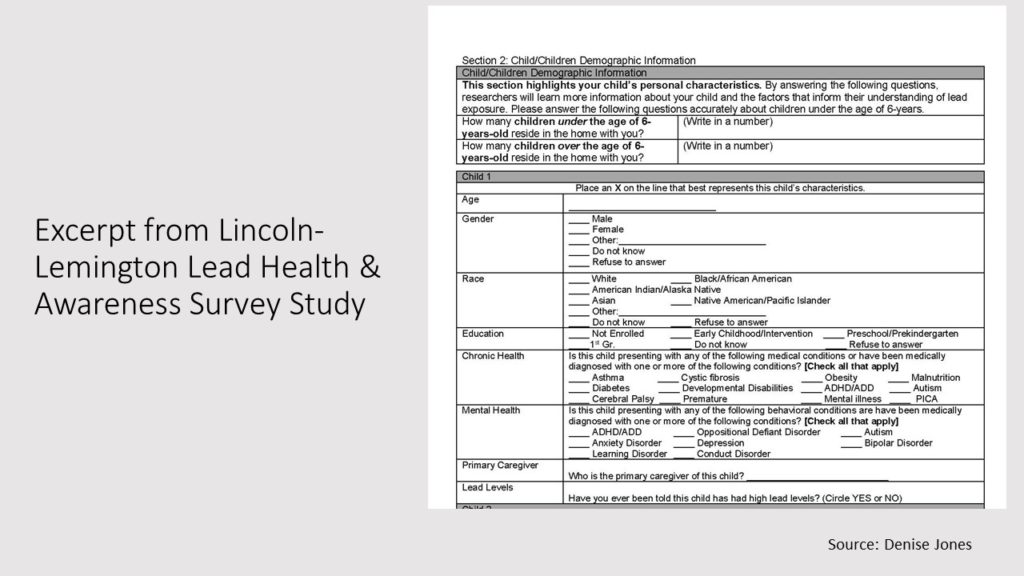

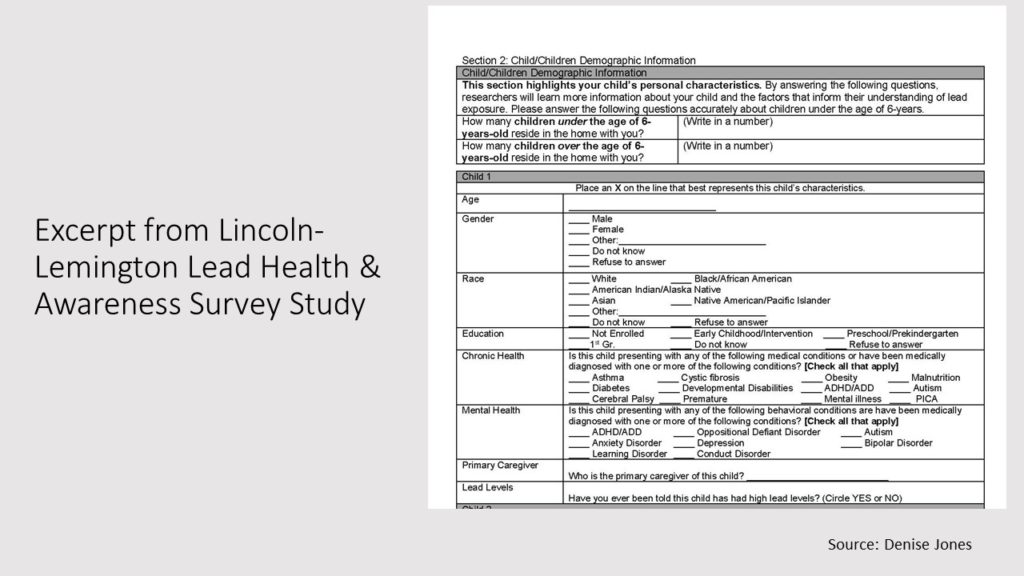

While I was preparing for this keynote, I ran across an intriguing example of what this looks like in a story from the Allegheny Front, a website dedicated to regional environmental journalism. The story profiled a local summer youth employment program in which teenagers are working in the predominantly black neighborhood of Lincoln-Lemington on lead poisoning (Holsopple, 2017). The neighborhood has older housing stock which means a higher likelihood of lead paint, and like many cities with aging infrastructure, Pittsburgh is grappling with serious lead concerns in its water lines. There is no safe level of lead exposure for children, but the CDC has established what is known as a “reference level at which the agency recommends public health actions be initiated” (CDC, 2017). The reference level is anything above a blood lead level of 5 micrograms per deciliter (µg/dL). In 2013, 7.5% of tested children here in Allegheny county had blood lead levels above the reference level, and several thousand more children have some level of exposure above zero (Allegheny County Health Department, 2015). The Allegheny County Council recently passed mandatory lead testing for one and two-year old children, and the law will go into effect on January 1 (Deto, 2017). A councilman supporting the legislation stated, “Lead testing gives us information, and without information we can’t assess the problem that we are facing” (Boren, 2017).

Over the summer, the students in the youth employment program mapped buildings in the neighborhood, talked with residents about their lead exposure mitigation strategies, and conducted surveys in cooperation with the Allegheny County Health Department. The students spent 3 days in Flint Michigan talking to activists and community stakeholders there.

I recently spoke to Denise Jones, who served as the project’s director . She noted that while there was much quantitative data, there was little qualitative detail. The Health Department might be able to say how many houses were built with lead paint or had lead service lines, but it didn’t have information on how caregivers employed various strategies to keep their children safe. Knocking on doors, clipboards in hand, these students filled in the care-based details that are all too often missing from records that rarely account for how our environments impact our lives.

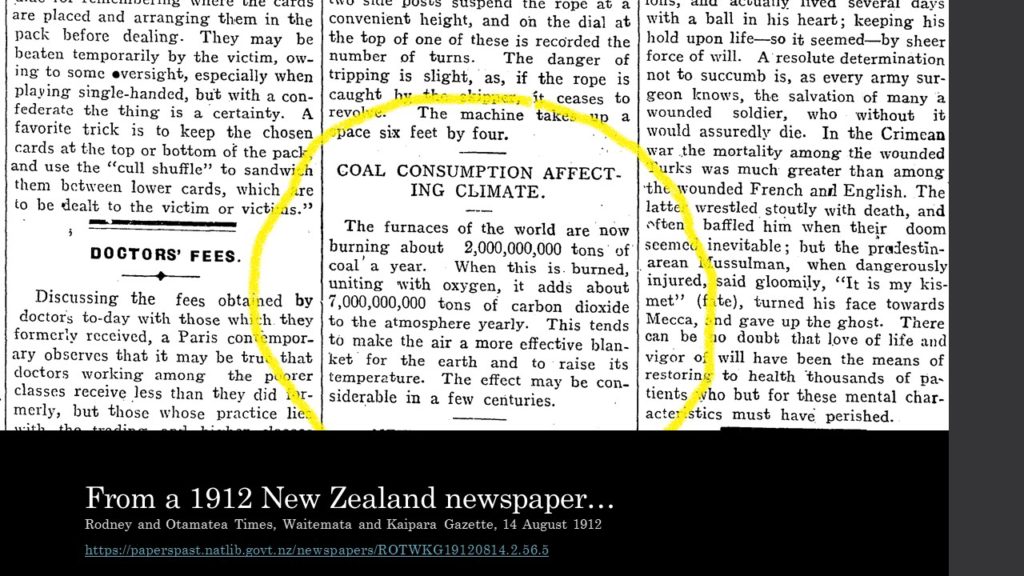

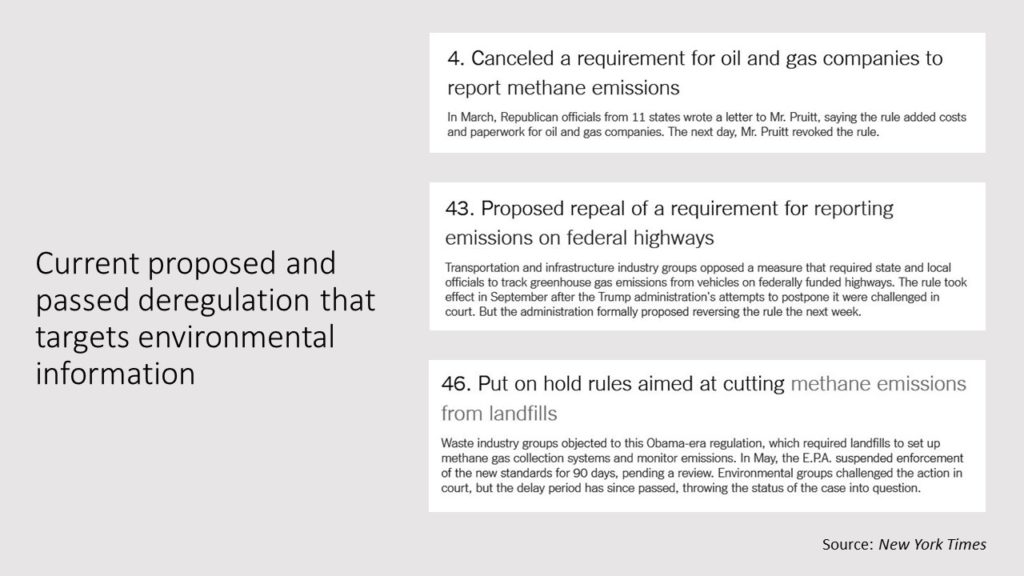

Preserving and making environmental information accessible is essential if we hope to bring any eventual accountability to power, because the legal and cultural context we live in requires documentary evidence in the form of trustworthy data and reliable records. Polluters know this, and it’s why rolling back regulations that document who is polluting and how is often the first line of attack in what they call bureaucratic red tape – but the documentation that that red tape creates is essential to building legal cases and moral claims against polluters. A disturbing number of today’s attacks on federal environmental protection involve attacks on information. Some of these have rolled back proposals for industry to increase its monitoring and reporting of methane. Methane has even more heat-trapping potential than carbon, and methane leaks are highly associated with fracking. Industry claims natural gas is a cleaner fuel than coal, but methane leaks undermine that claim. If we don’t require record keeping for methane emissions, it’s hard to determine the extent of our current contributions to greenhouse gas emissions.

I often think about how many libraries have an uncomfortable inheritance of what the Gilded Age steel industry wrought on air and water, and on the bodies of its workers. Andrew Carnegie made his fortune from steel and he made it here in Pittsburgh, and it was his philanthropy to over a thousand communities that nearly doubled the amount of public libraries in the United States. Many of our libraries and archives we work in are deeply tangled in fossil fuels – from institutional endowments invested in BP or Exxon, foundation-funded projects seeded from the money of oil and gas barons, preservation of our digital content on coal-powered servers, and reliance on fossil-fueled transportation to come together to dream of a better future. Environmental information is critical to our ability to meet the challenges that lie ahead, and I believe as information professionals we have an ethical obligation to incorporate environmental care in our professional practices.

I’ve been working around these issues of archives and the environment for a few years. The profession knows we need to do something, but we’re not really sure what it is. Should we rewrite our disaster plans to incorporate climate change? Should we put rooftop gardens and solar panels on top of our buildings? Should we incorporate the environmental footprint of cloud storage into our contracts with digital preservation services? Ideally we would all answer Yes to them – and yet they avoid the critical question of environmental information.

Before we can ask “What should we do about environmental information?” we must answer, “How do we as a profession develop an ethic of environmental justice?” Because we can’t sustain the issue of preserving environmental information for the long haul until we make caring about the environment a very normal and routine aspect of our personal and professional lives. People arrive at an ethic of environmental justice through different routes, but at its core, it depends on cultivating a sense of care and duty for the places in which we live and work, and understanding how environmental degradation compounds existing injustices.

In the archives profession, the “archivist as keeper and caretaker” trope has been thrashed for its implications that archivists are passive agents worshipping at the altar of neutrality. But as multiple archivists have recently asserted the importance of ethics of care in our profession, I would like to think we’re on the way to reclaiming archivists as caretakers in the best and most feminist sense of the word – that to care for something is a profound act of great importance, it’s essential to our ongoing existence, and it is the bedrock for preservation . To ensure that information is preserved so that it can be used by citizens for a safe and healthy environment is the opposite of passively keeping information – it is to assert that preservation of information, preservation of the earth, and preservation of public health, are very closely linked.

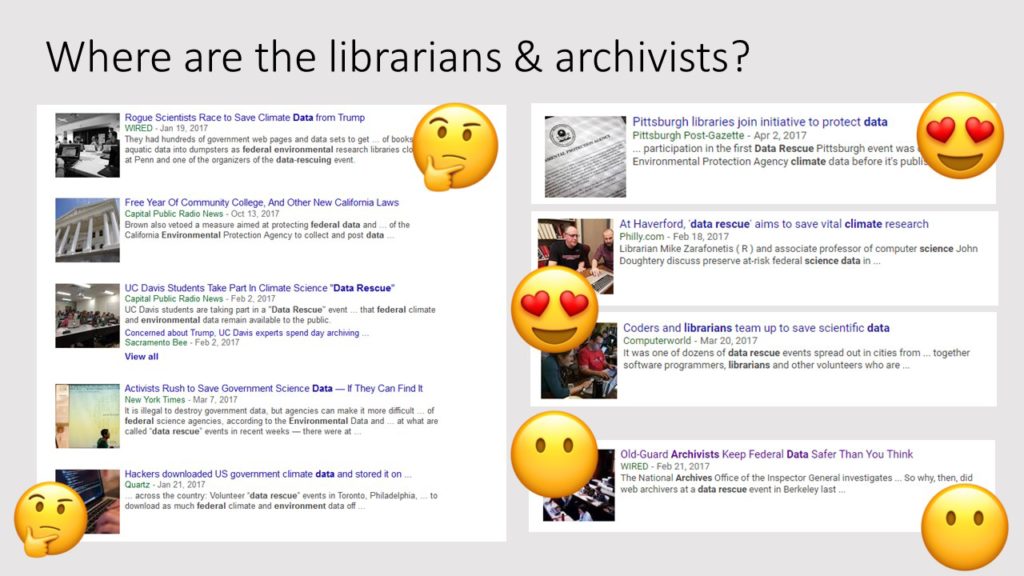

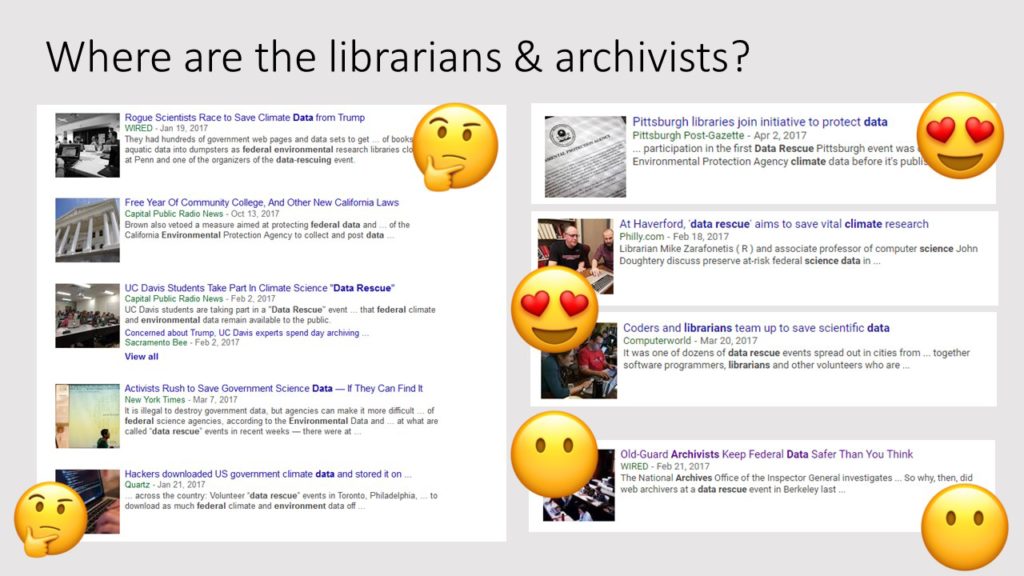

As we saw after the election, many decentralized efforts took place to address concerns over access and preservation of federal environmental data on websites like the EPA/DOI/NOAA/NASA. In some of those efforts, librarians and archivists played an active leadership role, while other efforts barely had any librarians or archivists present. Why was this? I suspect it is because for many of us, we do not have environmental justice incorporated in our sense of what it means to be an information professional. This information may be invisible to many of us most of the time, but if you like to breathe clean air and drink clean water, you should care very deeply about this.

As I’ve laid out, effective environmental protection depends on environmental information. That space is where we as information professionals most strongly bring our talents. So to return to the question, “What should we do about environmental information?” we need to identify the unfolding threats to its preservation and accessibility, from local to international stages. It’s not just at the federal level, and it was a problem long before the current administration, and will be longer after it. If we’re not given a seat at those tables, to paraphrase Shirley Chisholm, then we need to bring a folding chair. We need to assert that we, as information professionals, deeply care about environmental information, especially if we also claim that we care about the communities we serve.

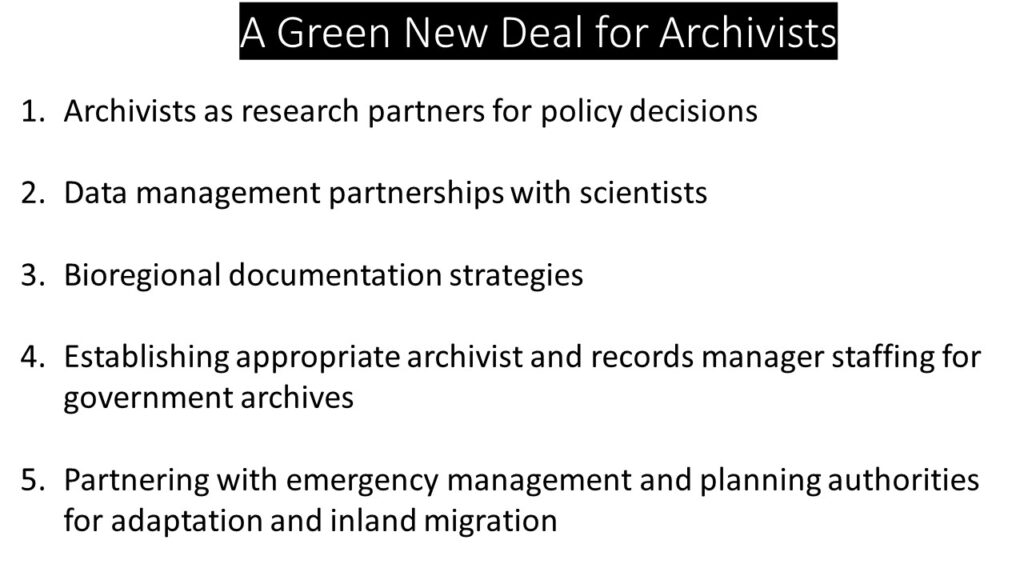

Just as there is not a single solution for climate change, but multiple paths to transitioning to a fossil-free future, there are multiple ways we can work towards ensuring environmental information is preserved and used:

- We can get involved in groups working on federal environmental data issues, many of which are represented within the DLF community

- We can become friends with scientists and journalists to organize around our common interests

- We can help citizen science projects with data management and preservation plans

- We can teach local environmental activists how to find and use environmental information

- We can surface new sources of environmental information in our collections, such as weather and ecological data from diaries

- We can prioritize local environmental topics for our collection development policies

- We can demand that industries voluntarily disclose more information about their environmental impact

- We can interrogate the appraisal and retention decisions of regulatory records to ensure records are retained long enough to support the public interest

- We can fight back against deregulation that rolls back reporting and monitoring recordkeeping requirements

The balance of power concerning the creation and access of environmental information has favored polluting industries for far too long. I’m gravely concerned this imbalance is becoming more severe, at the exact moment when crises of climate change, ecological collapse, and environmental injustice are becoming too urgent to ignore any longer. Whether we identify as librarians, archivists, curators, records managers, or some other branch of the information profession family tree, all of us can – and need to – contribute to preserving environmental information and ensuring its usability.

Rachel Carson lamented in Silent Spring that the evidence against pesticides was stacking up, but far too many people chose to ignore it.

She wrote, “Much of the necessary knowledge is now available, but we do not use it. We train ecologists in our universities and even employ them in our governmental agencies but we seldom take their advice. We allow the chemical death rain to fall as though there were no alternative, whereas in fact there are many, and our ingenuity could soon discover many more if given opportunity.”

Rachel Carson wrote those words more than 50 years ago, and yet it feels as if it could describe our world today. We need to build an alternative world, rooted in advice and ingenuity. We have the necessary knowledge. Now let’s use it.

References

Allegheny County Health Department. (2015). Community Health Assessment. http://www.achd.net/cha/CHA_Report-Final_42815.pdf

Boren, J. (2017). Allegheny County Council approves lead testing requirement for children. Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. http://triblive.com/local/allegheny/12478182-74/allegheny-county-council-approves-lead-testing-requirement-for-children

Butler, E., & Russell Sage Foundation. (1909). Women and the trades, Pittsburgh, 1907-1908. New York: Survey Associates. https://archive.org/details/pittsburghsurvey01kelluoft

Carson, R., Lear, L. J., & Wilson, E. O. (2012). Silent spring. Boston: Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). (2017). Lead. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/

Congressional Research Service. (2015a). An Overview of Unconventional Oil and Natural Gas: Resources and Federal Actions. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43148.pdf

Congressional Research Service. (2015b). Hydraulic Fracturing and Safe Drinking Water Act Regulatory Issues. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41760.pdf

Deto, R. (2017). Allegheny County Council candidate Anita Prizio thinks county’s new lead-testing rule should go farther. Pittsburgh City Paper. https://www.pghcitypaper.com/PolitiCrap/archives/2017/07/24/allegheny-county-council-candidate-anita-prizio-thinks-countys-new-lead-testing-rule-should-go-farther

EIA (U.S. Energy Information Administration). (2017a). Pennsylvania Profile Analysis. https://www.eia.gov/state/analysis.php?sid=PA#2

EIA (U.S. Energy Information Administration). (2017b). Pennsylvania Profile Overview. https://www.eia.gov/state/?sid=PA

EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). (2016). Hydraulic Fracturing for Oil and Gas: Impacts from the Hydraulic Fracturing Water Cycle on Drinking Water Resources in the United States (Executive Summary). https://ofmpub.epa.gov/eims/eimscomm.getfile?p_download_id=530285

EPA. (2017). DDT – A Brief History and Status. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/ddt-brief-history-and-status

EPA. (2017). Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) and Federal Facilities. https://www.epa.gov/enforcement/federal-insecticide-fungicide-and-rodenticide-act-fifra-and-federal-facilities

Holsopple, K. (2017). “Teens earn and learn while educating their neighbors about lead exposure.” Allegheny Front. https://www.alleghenyfront.org/teens-earn-and-learn-while-educating-their-neighbors-about-lead-exposure/

Hurdle, J. (2014). “Pennsylvania’s Auditor General Faults Oversight of Natural Gas Industry.” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/24/us/pennsylvanias-auditor-general-faults-oversight-of-natural-gas-industry.html?_r=1

Nixon, R. Reorganization plans nos. 3 and 4 of 1970, message from the president. Congressional document, House Committee on Government Operations. July 9, 1970. H.Doc. 91-366. https://congressional.proquest.com/legisinsight?id=12896-2%20H.doc.366&type=DOCUMENT

Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2012). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. London: Bloomsbury.

Pennsylvania Auditor General. (2014). A Special Performance Audit of Department of Environmental Protection. http://www.paauditor.gov/Media/Default/Reports/speDEP072114.pdf

Souder, W. (2013). On a farther shore: The life and legacy of Rachel Carson.

Wing, F. (1914). “Thirty-Five Years of Typohid.” Kellogg, P. U., & Russell Sage Foundation. The Pittsburgh district civic frontage. New York: Survey Associates. https://archive.org/details/pittsburghsurvey05kelluoft

Woodall, C. (2017). “Trump: ‘I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris’”. Penn Live. http://www.pennlive.com/news/2017/06/trump_i_was_elected_to_represe.html

Footnotes

Comments Off on The Necessary Knowledge