What We Don’t Know About What We Can’t See: Information and Hidden Infrastructure

This is an annotated version of the lectern copy of my opening keynote on September 30 at Access 2019 in Edmonton. You can watch the recording here (or on YouTube). Around the time I accepted the invitation for this keynote, I had a bit of a personal reckoning about my professional carbon footprint. I’m very grateful that the hosts from the University of Alberta Libraries worked with me to allow me to stay over for the whole conference so I wasn’t a parachute-in keynoter (and if you go to the last slide, you can see the personal carbon disclosure I included – I was glad that the conference featured some discussion around the carbon footprints of library conferencing). As a result of their generosity in hosting me through the entire conference, I was able to take the time to get to know the conference community and Edmonton. I had an amazing time, and this invitation really prompted me to think about transnational environmental issues in a way I hadn’t previously. Ursula Franklin has been one of my guiding stars for the last couple years, and I tried to channel a lot of her energy and thinking as I wrote this. On the car trip I took around Michigan as part of my research, I re-listened to most of her Massey lectures. This keynote highlights what I think are the most profound challenges inherent to information access, political power, and fossil fuels.

Introduction

Thank you for inviting me to speak with your conference today. I’m very grateful for the opportunity to consider environmental information from a transnational perspective. Preparing this keynote sent me on a crash course into corners of Canadian history and environmental policy I never expected to explore. I feel that gentle critique is an essential part of friendship, and I hope during the questions section you’ll point out what I have inevitably overlooked.

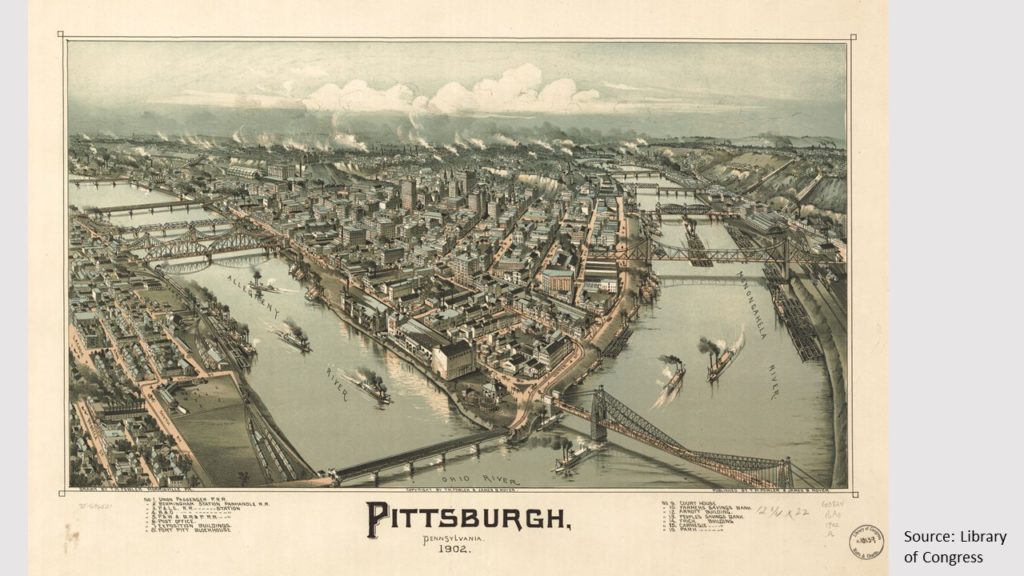

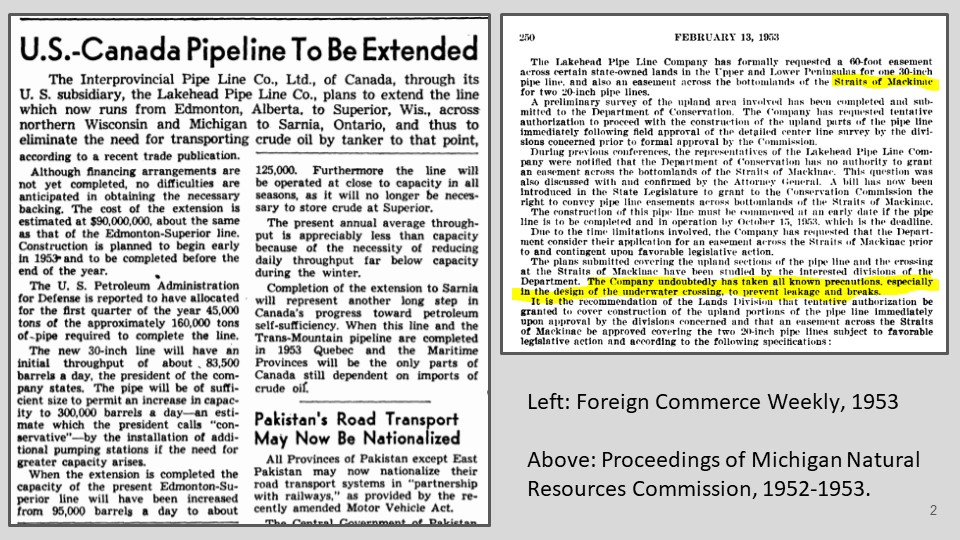

On the evening of August 15, 1953, a group of people gathered at the shore of one of the world’s largest lakes for a champagne toast from a set of bleachers. It was within view of the future site of the Mackinac Bridge, one of the world’s longest suspension bridges that would finally connect Michigan’s Upper and Lower Peninsulas after decades of ferry service. But the spectators weren’t there for the future bridge: they were celebrating the arrival of the first section of a twin pipeline that had just been been placed underneath a four mile channel of water at a depth of 250 feet. The arrival of the “North 30” twin pipeline marked one of the deepest water crossings in pipeline history up to that time. Aside from a few mentions in industry journals and Michigan’s legislative record, this milestone went relatively unnoticed elsewhere. And for the next 60 years, no one really paid attention to the pipeline underneath the Great Lakes.

I’m aware that most of you rarely engage with environmental information in your daily work life, except perhaps checking the weather report to determine whether to bring an umbrella to work. You’re probably at a library technology conference because some part of your job description involves using specialized technologies to organize and make information in your library accessible to its users.

But even if it’s not present within your job description, environmental information impacts your life on a daily basis. When you brush your teeth in the morning, the water utility that provides water to your residence is part of a larger infrastructure that generates vast amounts of data that is shared with regulators. The conditions in which your lunch food was grown, the air quality of the park that you may visit on the weekend, and the vehicle you used to get here, are all parts of larger infrastructures, which have reams of environmental information associated with it that you’ll never read or handle.

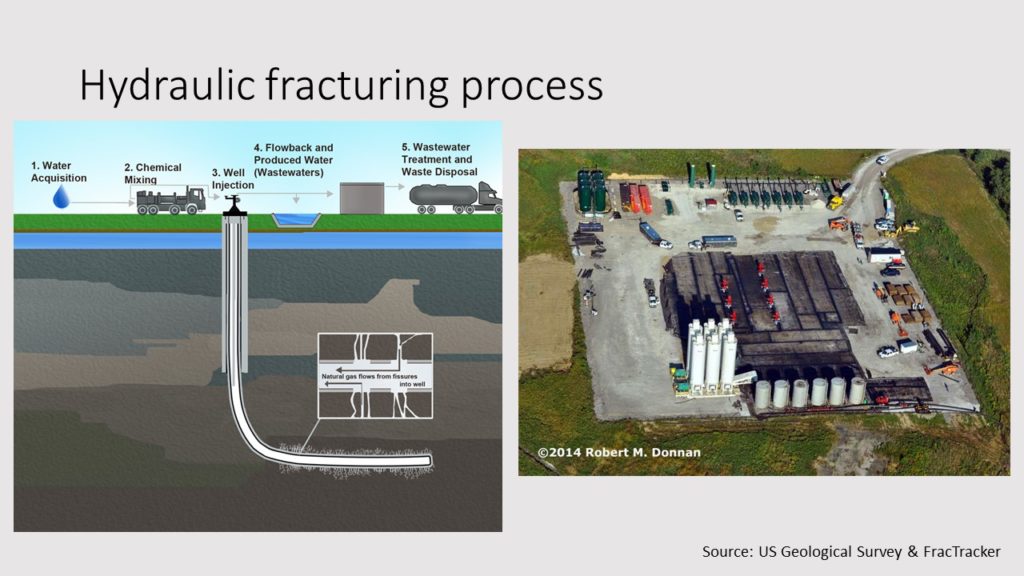

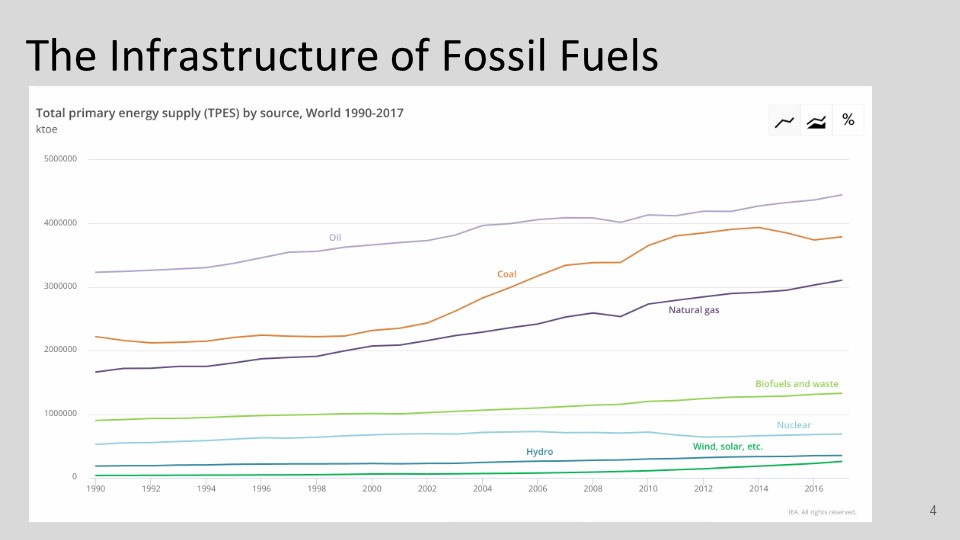

Perhaps the infrastructure that most deeply shapes every continuous hour of our lives is the one we’re sharing right now, as we sit beneath these lights and in this climate-controlled room that is powered by the infrastructure of energy production. The vast majority of energy used in the world – almost 80% of it – comes from fossil fuels. Fossil fuels occupy a particularly challenging position at the intersection of infrastructure and environmental information. Fossil fuels are removed from the earth, undergo significant processing, and are often transported thousands of miles away from the point of extraction, thus requiring a worldwide infrastructure for their use. And for any infrastructure to work efficiently, it requires significant amounts of data and information for its operation to know where and when things are coming or going.

So why should those of us here today care about the data of infrastructures outside of our institutions, for which we have no control over? And why especially should we care about the information with fossil fuels, which probably has nothing to do with our job description? I argue it is because librarians and archivists are uniquely positioned among professions to understand how the use of information, and the lack of access to it, impacts communities. Fossil fuel interests in the United States and Canada benefit enormously from a legal framework that allows them to shelter enormous amounts of information from the public. This has serious consequences in the short-term for those who live near the locations of fossil fuel production and transportation infrastructure, but also for the long-term, since everyone alive today and tomorrow will be subjected to the consequences of climate change caused by burning fossil fuels.

You may have heard the figure that just a few dozen companies are responsible for the majority of world emissions. If a patron where you work asked whether your library had information on the business practices of the US or Canadian companies on that list, what could you tell her? You might be able to track down annual reports to shareholders or mandated disclosures to regulators, but what if she wanted information beyond what was in those reports? The answer is that you would quickly hit a brick wall, because so much of it is locked up within the companies themselves. And so we are in a position where in the largest challenge facing humanity today, we librarians and archivists do not have the means to help others access necessary information about these companies because so much of it is private. Not only is this information not in our libraries, it’s often not even in the public domain.

Fossil fuel infrastructure has another challenge associated with it: unlike the roads we travel every day on, its infrastructure is often hidden. It is underground or in fenced off structures we cannot access. In many cases this is for good reason: there is not room aboveground, or the exposure of pipelines to the elements can speed up wear and tear. But the effect of hidden infrastructure is that many of us do not think about what we cannot see.

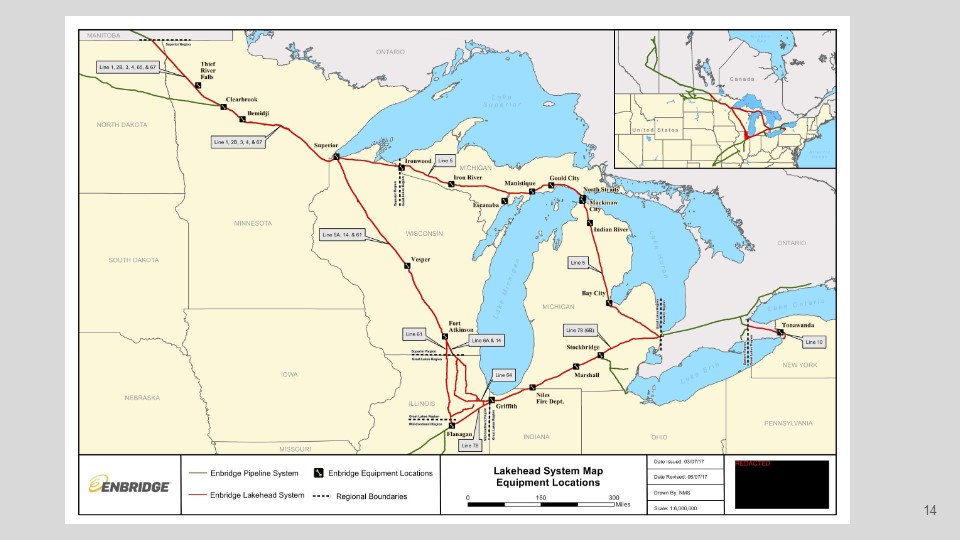

When we cannot encounter hidden infrastructure firsthand in our daily lives, then information about that infrastructure is the closest proxy we have for being able to observe it. Since most pipelines are hidden in the landscape, pipeline maps are essential forms of infrastructure documentation. A consistent difficulty with infrastructure information is that often times different jurisdictions take radically different approaches to presenting similar contents.

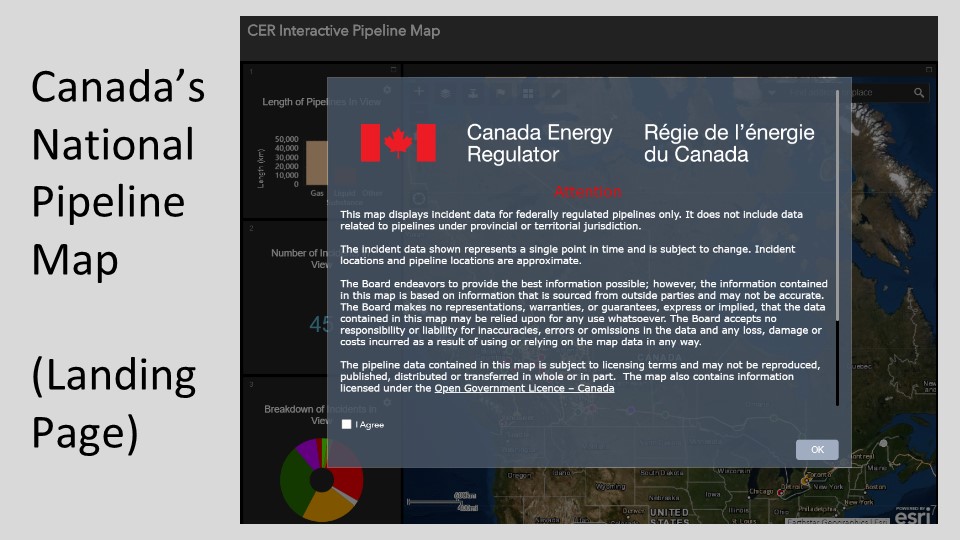

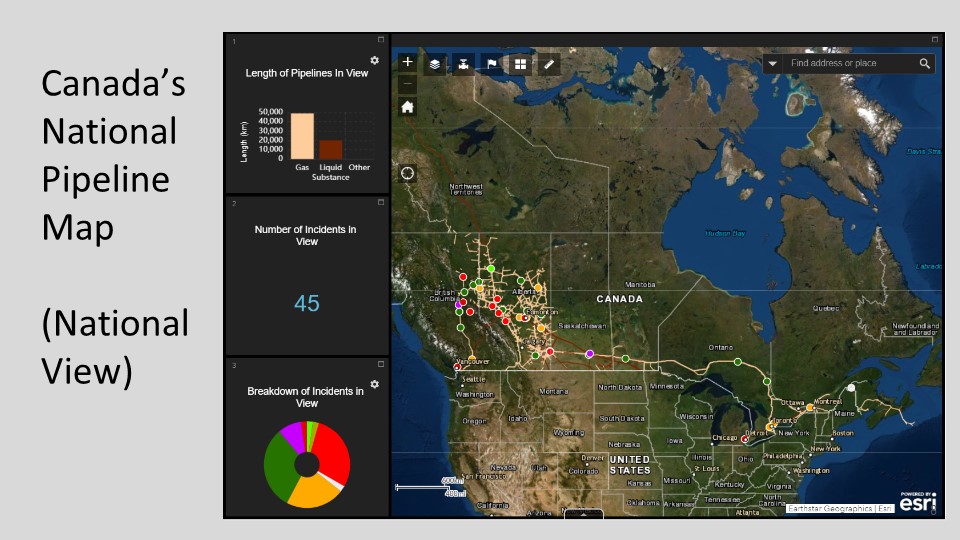

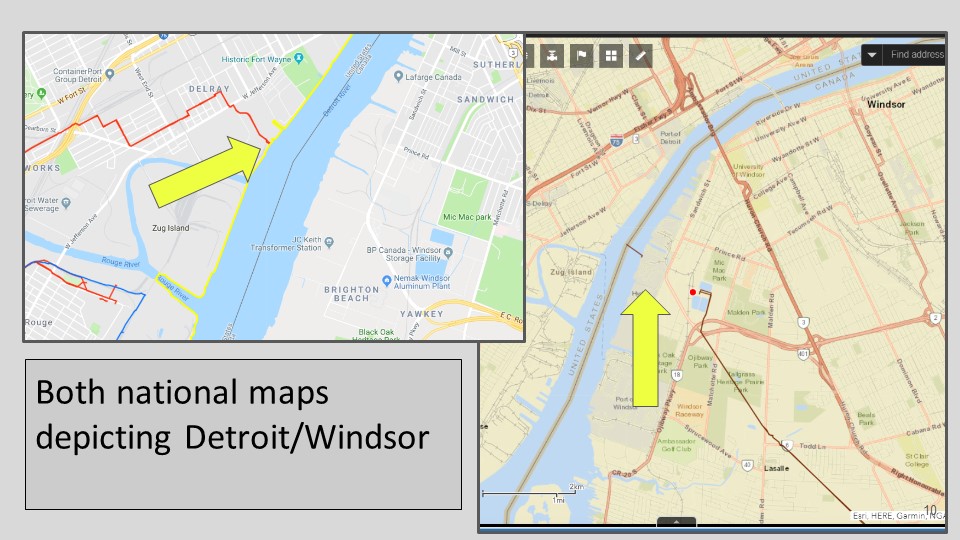

The United States and Canada both maintain national pipeline map websites, and both have similar forms of information, but Canada’s map and the United State’s map involve radically different user experiences. I want to start with this example because it shows how deeply technology mediates our experience of accessing information about infrastructure.

When you start on the Canadian pipeline map, you get a disclaimer and after saying “Yes I agree” you automatically see everything and can pan and scroll around.

You can enter an address, if you want, but if you just want to zoom in and out from Ontario all the way down to a city and back again. You also get some useful data points on the left hand side about incidents and pipeline miles.

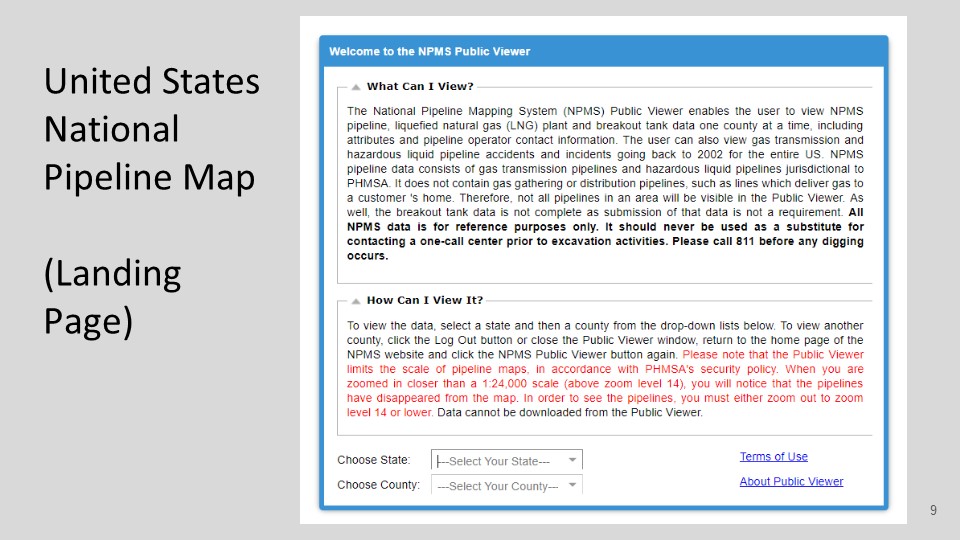

Now, contrast this to the United States’ pipeline map, which immediately informs you in stern language that because of security concerns, you can’t zoom in past a certain threshold. For what it’s worth, this is roughly the same zooming capacity as Canada, but I appreciate that Canada doesn’t insinuate I might be up to no good just because I want to understand the geography of fossil fuel infrastructure.

But then, the United States map does something truly weird: it makes you enter a state and county. This is the first sign that this map is not designed with the general public in mind. For scale – Ohio itself has 88 counties, and I can only name about half a dozen. What if you want to view a multi-county area? Too bad – you’re limited to one at a time.

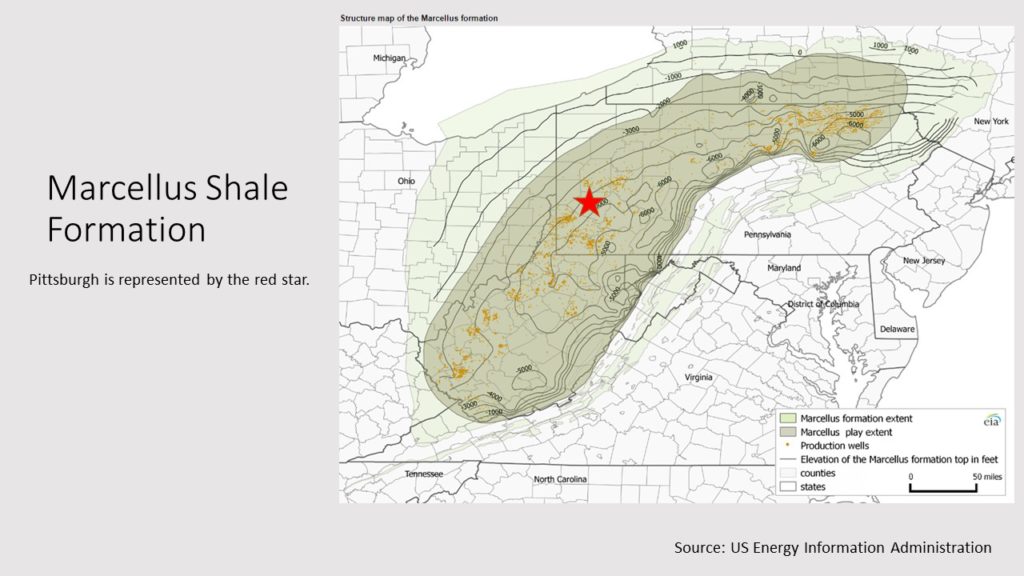

In her talk “The Tool Shapes The Task”, Ursula Franklin talked about how the tools we use shape the types of work we can do. What the US map forces us to do by selecting a county is to consider a pipeline only within the boundaries of a single small political jurisdiction – it doesn’t allow you to look at the pipelines from say, Ohio to Michigan or Cleveland to Chicago. The local examples on the slides depict Detroit and Windsor, which are on either side of the river separating the US and Canada. You’ll notice that neither map showed how pipelines cross borders – and not only do pipelines routinely cross political jurisdictions, they also cross watersheds.

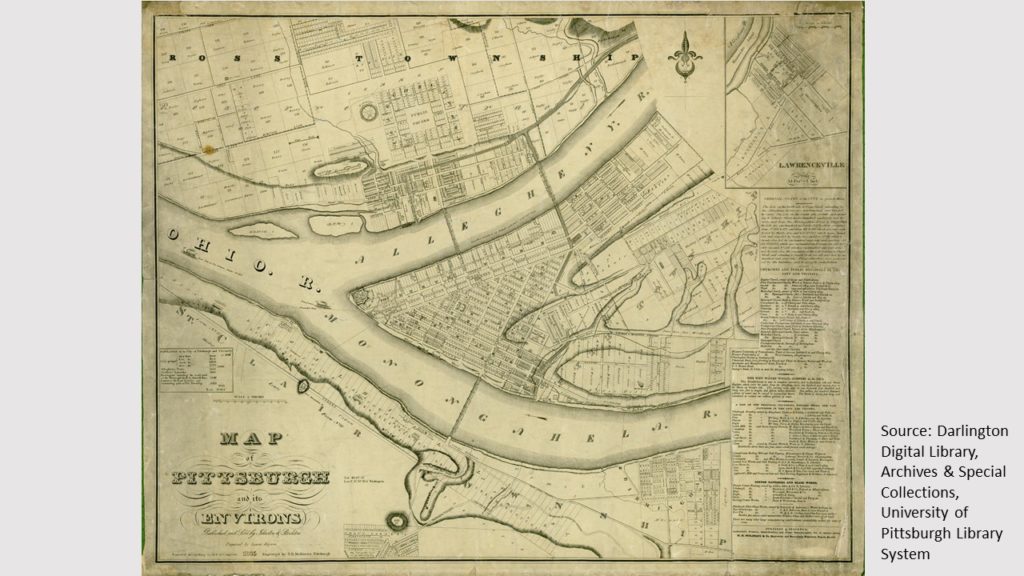

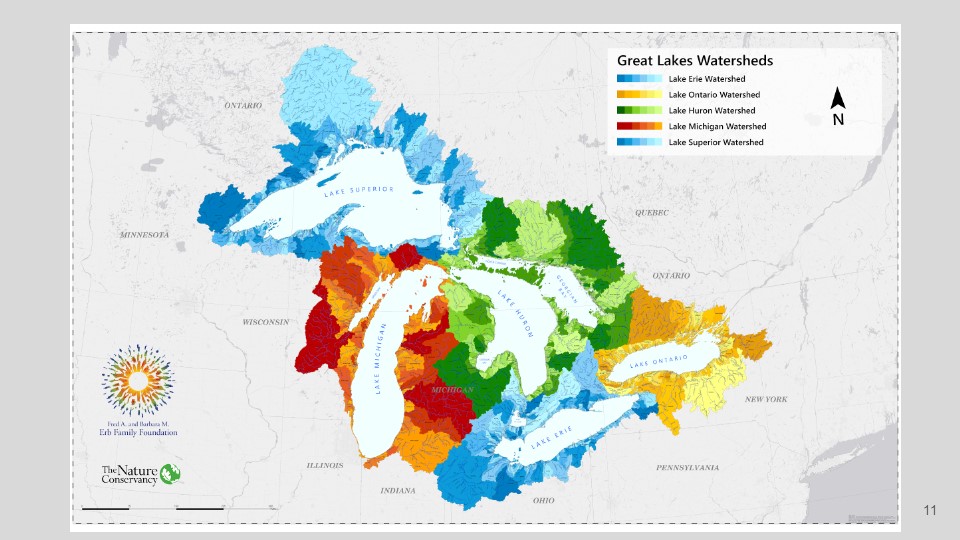

One of the largest transnational watersheds on Earth is the Great Lakes, consisting of 5 major interconnected lakes spanning 750 miles (or 1200 kilometers). Many people think calling them lakes doesn’t do justice to communicate how vast they are, and so they are also described as an inland sea. When you stand at the edge of a Great Lake, you usually can’t see the other side. What you see instead might be waves. They contain roughly 21% of the world’s surface freshwater – and about 84% of North America’s freshwater.

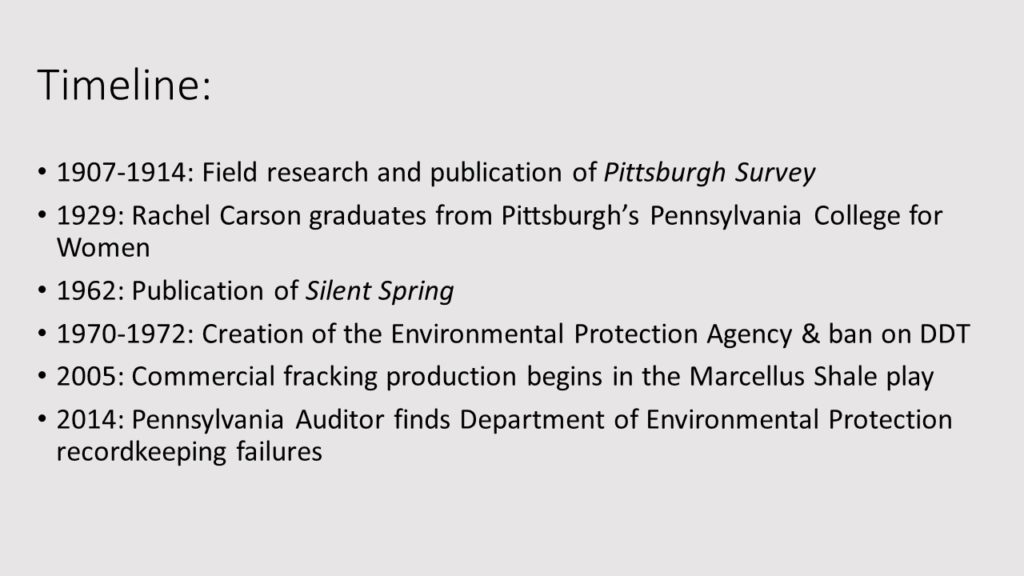

Almost a quarter of Canadian agricultural production takes place within the watershed. Roughly 10% of the U.S. population and more than 30% of the Canadian population lives in the Great Lakes region. The Lakes region provided the cities in the region shipping routes and water for manufacturing, but it also provided a convenient place to discharge pollution – leading to infamous milestones in US environmental history such as Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River catching on fire – multiple times – due to industrial discharge. Although environmental law has significantly improved the waters of the Great Lakes since then, we rarely consider the hidden infrastructure of oil and gas pipelines that can threaten the largest source of freshwater for the US and Canada.

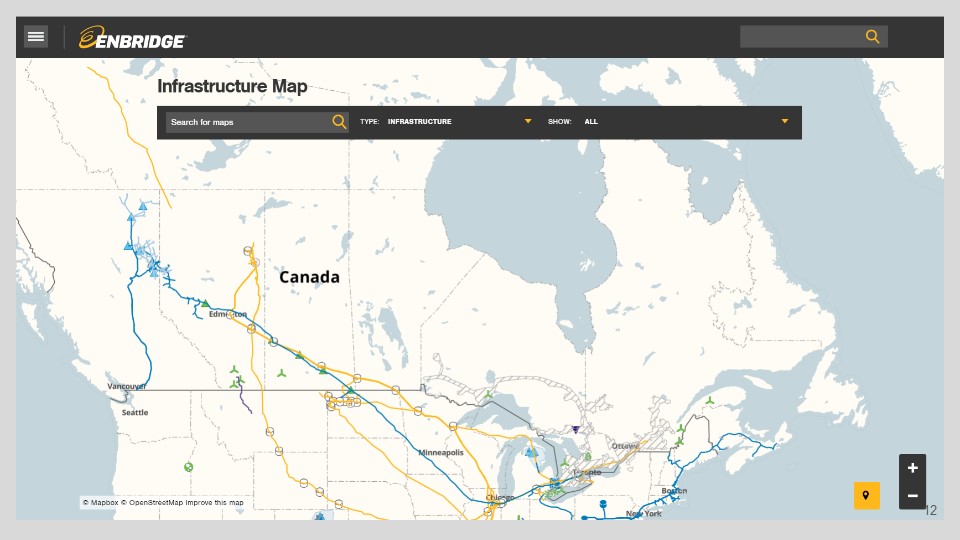

The pipelines around the Great Lakes are directly linked with the history of oil production in Alberta. The Lakehead pipeline system around the Great Lakes began being built in the 1950s by Interprovincial Pipeline, which was a subsidiary of the Imperial Oil Company of Canada, and was the predecessor company of Enbridge. This pipeline system was designed to transport crude oil that was being produced in Alberta’s newly discovered Leduc oil fields. The first phase of the pipeline went from Alberta to Superior Wisconsin. The company then put oil on tanker ships that crossed the Great Lakes to Sarnia, Ontario for further refining. But the increasing production of oil – along with the fact that the Great Lakes iced over every winter – meant that the company looked to build a pipeline to facilitate transportation. The company considered two routes – one, an entirely overland route that would have routed the pipeline from roughly around Chicago to Sarnia – in other words, on the southern US edge of the Lakes. The second route was one that ran the pipeline through Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, down through the Straits of Mackinac, and then through Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, and over the Detroit River to Sarnia. If you’re wondering whether the company ever considered a third option – of routing it entirely through Canada – well it never really did, because it would have cost $10 million more and added an extra 120 miles of routing.

The company decided on the second option, through the Straits of Mackinac, because it was the shorter route. Remember, this all took place in the early 1950s, which was at least a decade before many of the major US environmental regulatory laws that required serious consideration of the environmental impact of major engineering projects. As a result, the entire design and construction process was remarkably swift, beginning in 1952 and going into operation in 1954.

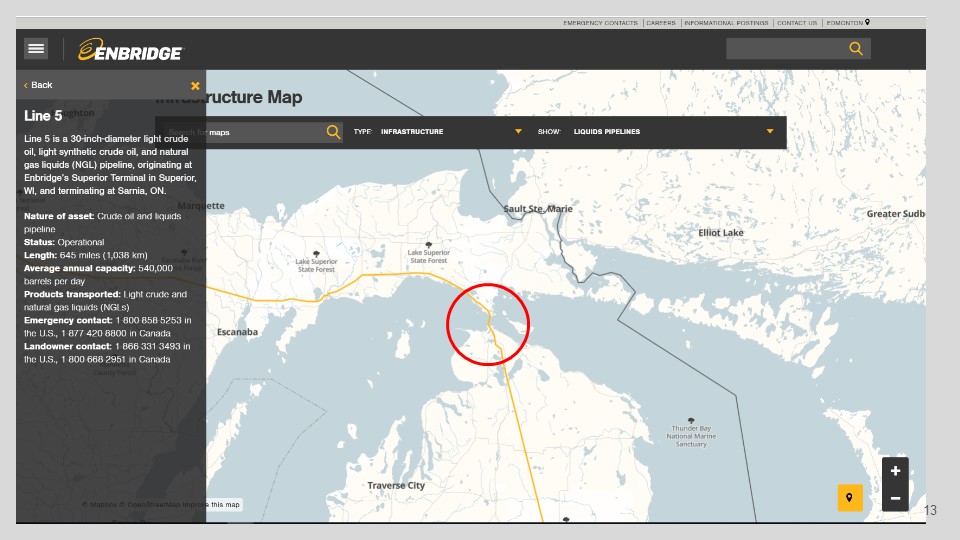

The routing of the pipelines through the Straits of Mackinac has turned this pipeline into one of the most contested pieces of aging fossil fuel infrastructure in the United States. In large part, this is due to the Straits location at the juncture of two of the Great Lakes, Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. The channel is about five miles wide, and due to winds, the currents in the channels change very frequently. While an oil spill in any environment is bad, it would be particularly bad here because the current changes would make it difficult to model where the oil would go.

Today this pipeline is known as Line 5. Line 5 has not yet had an oil spill in the Straits – so why has it become the source of significant attention?

In 2010, another Enbridge pipeline, known as Line 6B, began leaking near Marshall, Michigan. More than 840,000 gallons of diluted bitumen leaked into tributaries of the Kalamazoo River over the course of two days. The result was that the Marshall spill became one of the largest inland oil spills in the last several years. If this never crossed your radar, it may be because the largest oil spill in history was still taking place during the same summer in offshore Louisiana with the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

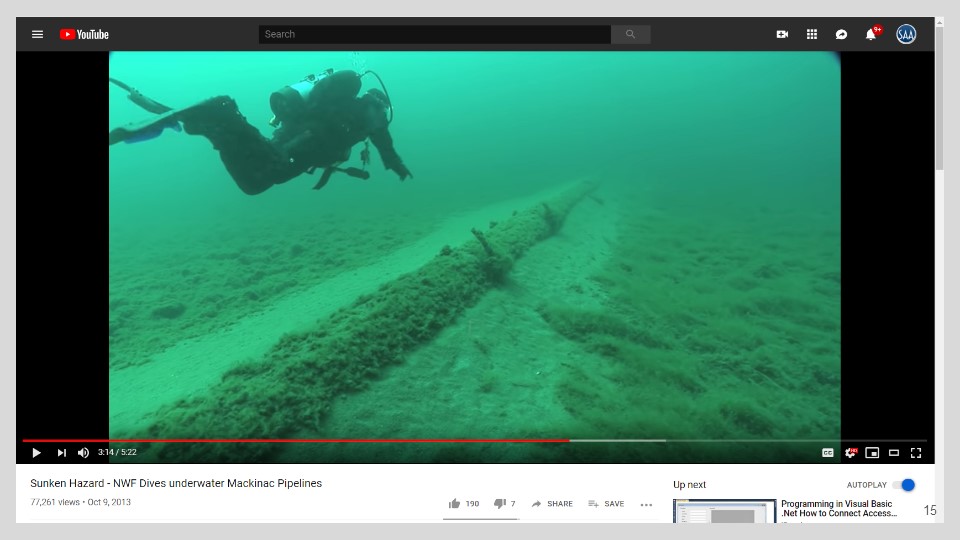

After the Marshall oil spill, the National Wildlife Federation began drawing attention to Line 5, and in 2013 used scuba divers and underwater videos to publicly document the condition of the pipelines in the Straits. From this image, you can see that the pipeline has many mussels that have stuck to it, which Enbridge claims are not affecting the integrity of the pipeline – though I would have to imagine they make inspections more difficult. Following this report, the state of Michigan convened two major state-wide committees to implement pipeline safety standards and issue further recommendations. Many of the recommendations involved transparency and access to information about pipelines.

One of the most challenging aspects of information about hidden infrastructure is that it is often deliberately inaccessible to the average person because of who created it. While the federal government can tell me what pipelines are nearby and what they carry, only the company operating it could tell me whether it is currently transporting petroleum, natural gas liquids, or something else.

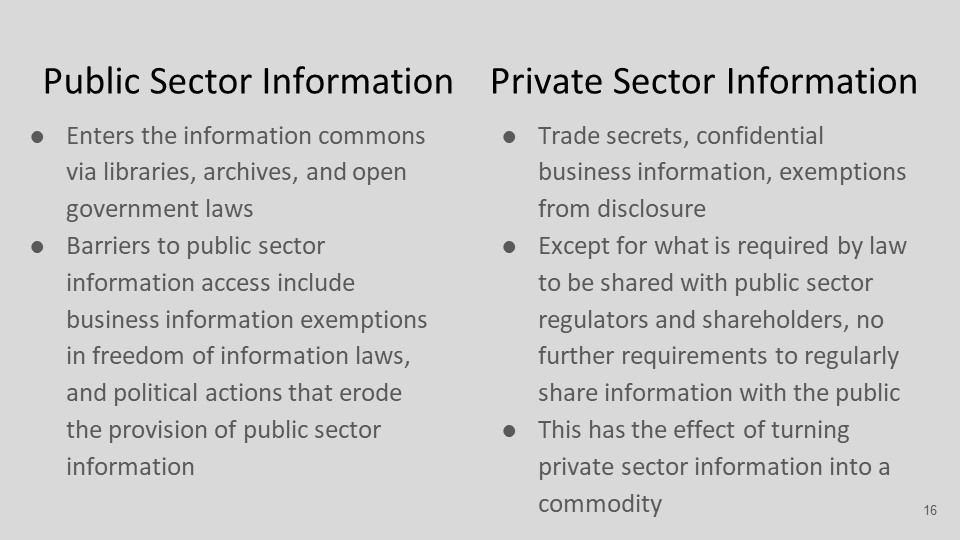

The provenance, or source, of information often determines whether information is treated as a commodity – in other words, something with a kind of monetary or property value that isn’t accessible to all people, or whether it is treated as part of the commons, meaning everyone has shared and similar rights of access.

By and large, environmental information created by the public sector in jurisdictions with open government laws is theoretically available to the public. I want to heavily emphasize the word theoretically: there are glaring exceptions to accessing information across the public sector, especially depending on who has political control. The systematic funding and management issues of Libraries and Archives Canada, and the Harper government’s 2014 closures of several federal libraries associated with environmental agencies show that even information held by the public sector today is not guaranteed to be accessible in perpetuity. Laws matter as well: Canada’s Crown Copyright application means that government documents are not as freely available compared with the United States, in which government documents are part of the public domain.

But the distinction between public and private sector information provenance is still crucial: if it’s created by the public sector, there is a larger body of legal doctrine and precedents across many diverse jurisdictions supporting the idea of public right of access. Freedom of information laws are not the only tool that ensure public access to public sector information: the role of records management in assessing agency records for transfer to archives, or federal depository programs for government documents in libraries also serve to move information created by the public sector into an information commons.

In contrast, information created by private entities is considered a commodity and not part of the commons. Because of the privileged role that private sectors are accorded within the legal systems underpinning capitalist economies, information is treated as company assets that may be sheltered from the public as trade secrets, confidential business information, or other forms of protection from disclosure. Disclosure of this information has the potential to undermine a company’s capacity to maximize profits, by either damaging its reputation or value, providing fodder for lawsuits, or making it vulnerable to competitive action. When you delve into legal scholarship on how the courts regard business information, the classic examples that come up are things like protecting Coca-Cola’s right to maintain its recipe a secret.

But where things get quite murky, and from my point of view, very alarming is the fact that courts are very deferential to business information as a commodity even when it has serious implications for public interest. Except for information that corporations must share with regulators and with shareholders, they are not otherwise required to share information to the public. Of course, many corporations do voluntarily share information, but voluntarily sharing information is not the same thing as guaranteed statutory access to it.

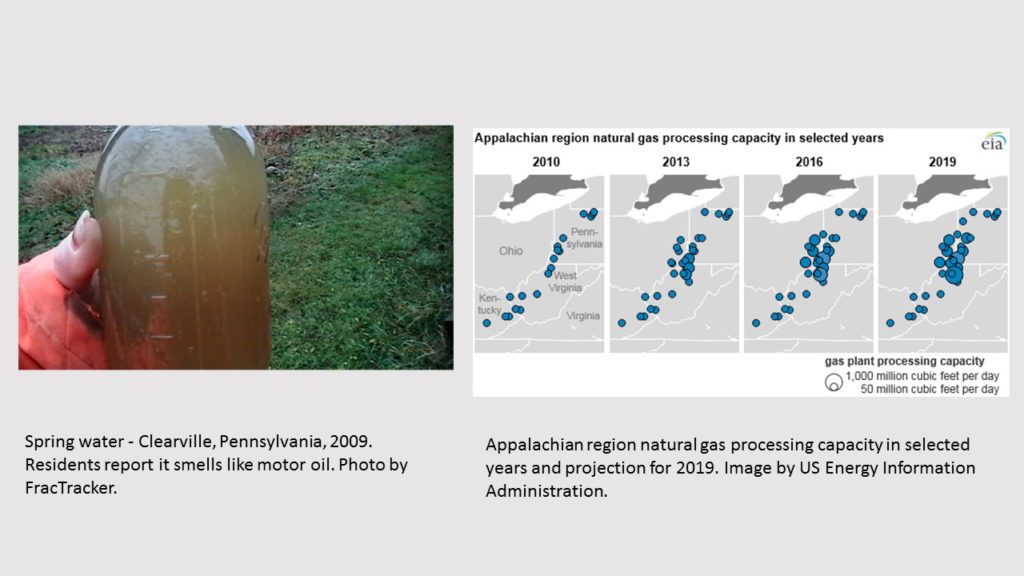

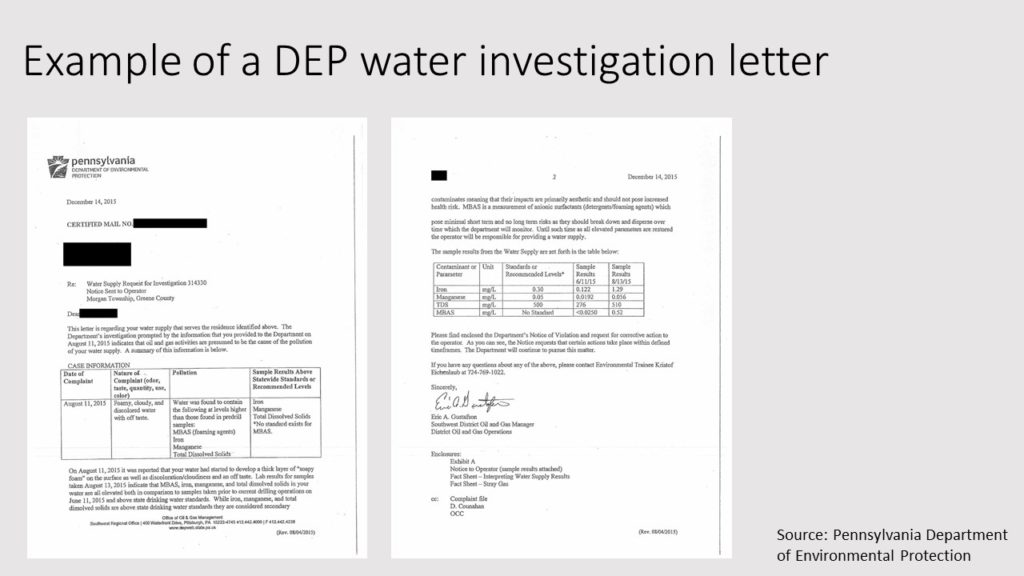

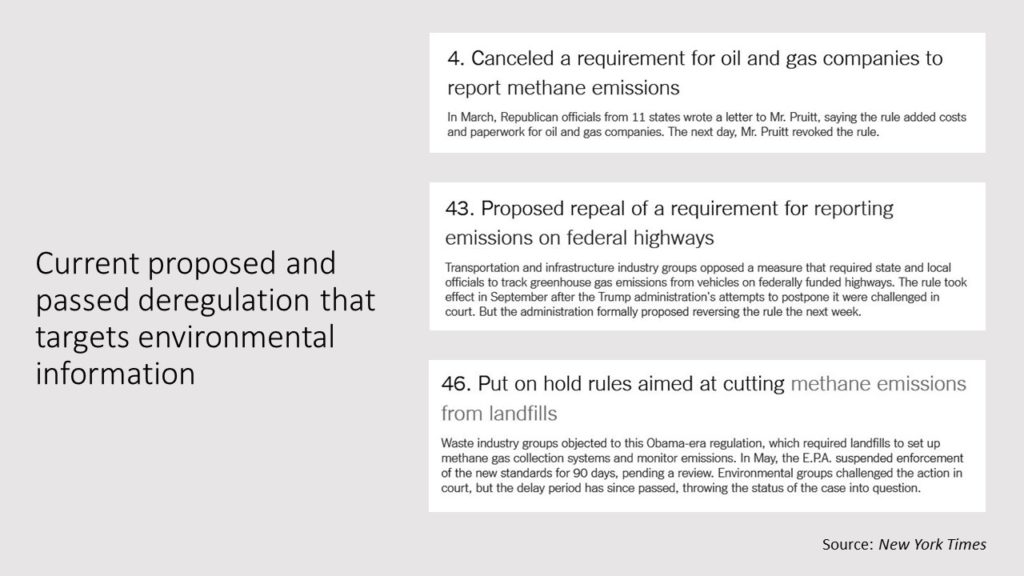

In the world of people who study environmental policy, there is something known as information asymmetry. This is a way of saying that one party has more information on a particular issue than another. When it comes to environmental regulation, often times companies involved with natural resource development have more information on the potential impact of their activities than regulators have, which poses challenges for regulators to do their job on behalf of the public.

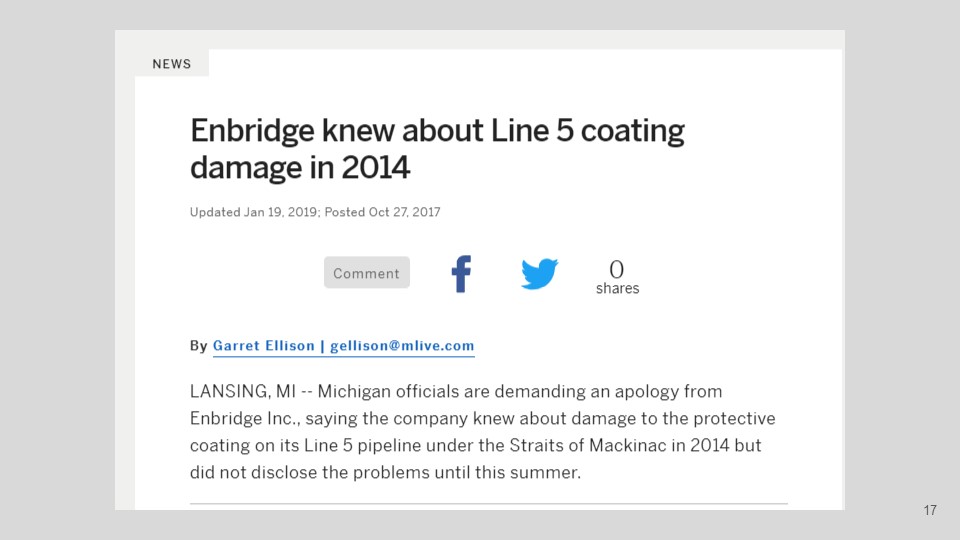

Furthermore, regulators have to trust that the corporation is sharing authentic and accurate information with them, and there are many examples of companies that withhold information from regulators, both accidentally and deliberately. When corporations are compelled to disclose information to regulators, not all of this information becomes public. While ExxonMobil discloses much information to SEC/EPA, I cannot FOIA everything they have submitted because there are many confidential business information exemptions in FOIA.

A serious example of an information asymmetry took place when Enbridge officials misled the state about the protective coating on the pipelines in the Straits. In March 2017, the Michigan Pipeline Safety Advisory Board asked Enbridge about the protective coating on the pipelines in the Straits, and the company told the board it was “intact.” However, five months later information came out showing that Enbridge knew as far back as 2014 that there were gaps in the coating, resulting in the state ordering Enbridge to conduct an investigation.

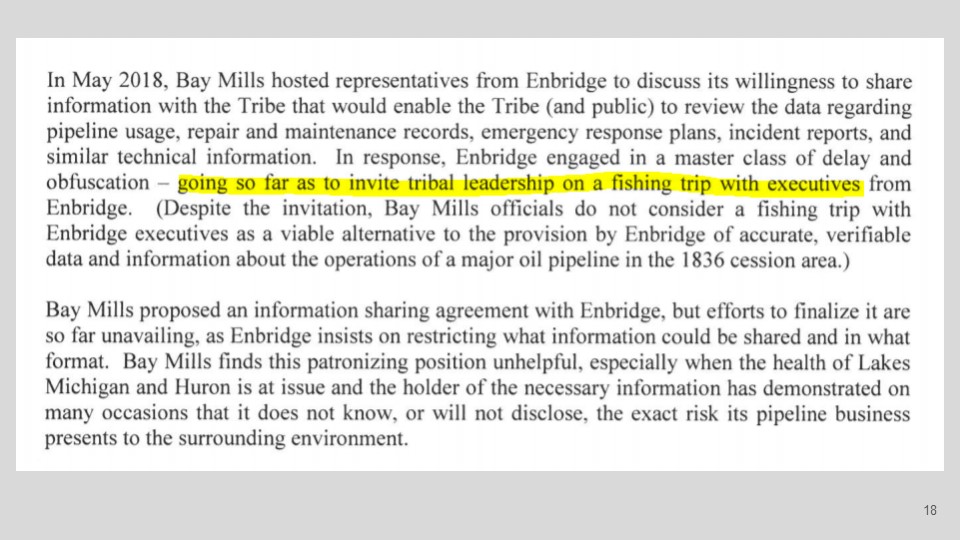

Information asymmetries have also arisen with Enbridge not sharing information with indigenous governments who have treaty and consultative rights to the land and water through which Line 5 runs.

Dozens of tribes in the Great Lakes region have issued statements against Enbridge Line 5, and a few of them are beginning to initiate legal action against the company. The Bay Mills Indian Community in Michigan has repeatedly sent requests to Michigan’s state officials and Enbridge requesting that the company share the same information it does with other government officials. According to tribal leadership, when they attempted to meet with Enbridge in May 2018 to discuss information sharing, the company executives invited them instead on a fishing trip. The tribe noted that a fishing trip was not exactly a viable alternative to sharing information.

There is often a temptation to try to solve information asymmetry issues with technology. There’s a prevailing sense that building a website or making a data set available to download is the same thing as transparency.

This is the “just add technology” theory of transparency, a theory that avoids the messy political question of what information exists in the commons and what information has been commodified but is of public interest. It also often sidesteps questions of maintenance, such as whether funding and staffing will be allotted to ensure that any technology used in the service of transparency delivers on its promises. The “just add technology” theory of transparency can be seen in the state of Michigan reports – if you read them carefully, it is clear that there is not consensus around increasing the legal means to make information available, but to use technology to make already existing public information from the state more accessible. Perhaps this is because both of the committees that existed between 2015 and 2018 included representatives of the energy industry.

The main transparency initiative that was actually carried out as a result of the two reports was the creation of a website, mipetroleumpipelines.com, administered by two of Michigan’s state agencies.

In the board’s final report, the recommendation pertaining to the website stated that the website would continue to be maintained through at least 2020. The recommendation suggested the website should have maintain maps, educational guides, legal primers, and “updates on the future of Line 5.”

The 2018 report was submitted on December 20, 2018. And this appears to be about the last time anyone thought about updating this website. The last news release on the website was posted the day after the final report, December 21. There are no maps. There is no information about the current regulation of pipelines in Michigan. There are no education primers. There are no links to major cases.

But perhaps what is most concerning is the lack of Line 5 updates – and there have been scores since December 2018. Less than 2 weeks after the Pipeline Safety Advisory Board submitted its final report, new state government leadership was sworn in, including a new governor and attorney general who campaigned against former governor Rick Snyder’s plan for maintaining the pipelines in the Straits of Mackinac by building a tunnel over them. Earlier this summer, the attorney general filed a lawsuit to shut down the portion of Line 5 in the Straits.

Despite many of these developments within state government – there is not a single update on the website showing anyone has worked on it in 2019.

I emailed the Public Information Officer of the Michigan Agency for Energy on August 28 to ask when the website would be updated, and was referred to two other individuals. Despite following up, they still have not responded to my follow up emails.

Finally, I want to show you how ultimately political power is the key question to who has information they’re willing to give you.

If you look at Enbridge’s website, it has this very glitzy page that says “Communication is a two-way street. We want to hear from you, and address any concerns you may have about our pipeline operations.” Well that sounds promising!

Unfortunately, a two-way street apparently includes some dead ends in Enbridge’s world, as I have been going around in circles with their PR representative asking for information.

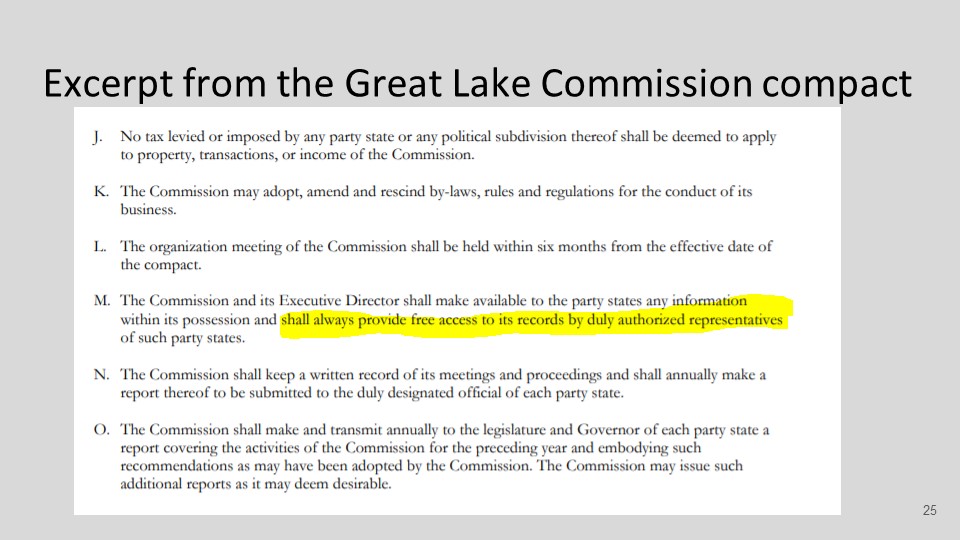

Second, even entities developed to serve the public are not great about making information available, if it’s not part of their mandate. Within the world of environmental regulation, transboundary issues are often managed according to legal compacts or agreements between different political jurisdictions. The Great Lakes Commission was created in 1955 due to the Great Lakes Basin Compact. It has 8 member states and the provinces of Ontario and Quebec are associate members. The commission is responsible for coordinating the “development, use, and conservation” of water in the Great Lakes watershed. As an interstate compact, the commission is doing work on behalf of the public, and yet there is not a way to file a public records request with the commission, and the compact’s own language reserves the right to access records only to member state’s designated representatives.

I wanted to review the Commission’s annual reports from around the time of the Line 5 construction to see if there was any discussion of the pipeline construction. I emailed with GLC several times, and even offered to visit their headquarters in Ann Arbor but was ultimately told: “The Great Lakes Commission does not have any kind of public library available on-site. Our offices are not open to the public, nor do we offer document reviews such as you are requesting.”

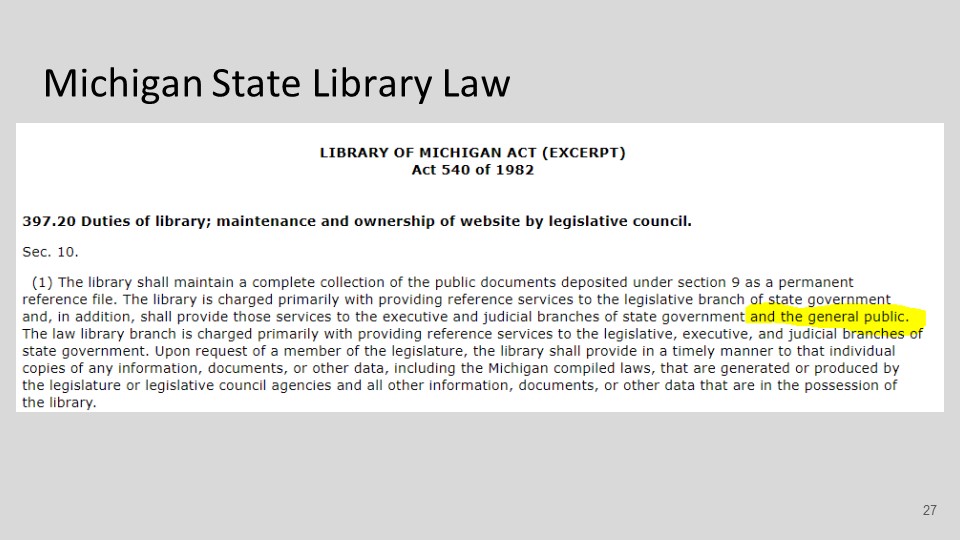

Luckily, I did find someone willing to share information with me, and that is the State Library of Michigan. Under a law passed by the state in 1982, the Library has a legal mandate to preserve state documents for public access. I started poking around the Michigan state library catalog a few months ago when I was planning a research trip to the state. I only had a few hours to spend at the library, but there were dozens of documents I wanted to review and knew I wouldn’t have time to pull. On a lark, I emailed the reference librarians to ask if it would be possible to pull everything I wanted to look at in advance, and they were kind enough to have a fully-stocked book cart waiting for me when I arrived.

Now I’m sure that the people who work at Enbridge and the Great Lakes Commission are also very nice and probably want to be helpful. But the difference between them and the State Library is that only the latter is required, by law, to serve the public. And so it is ultimately political power that gets information into the hands of the public.

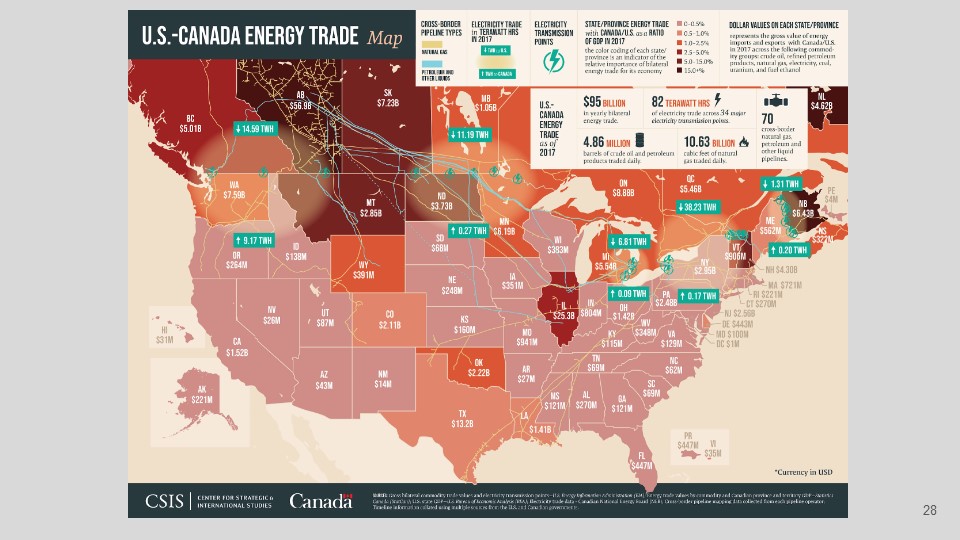

As we confront the challenges of accessing information around pipelines and oil production Canada and the United States, it is worth zooming out to consider the fact that both states arguably operate as petrostates. By petrostate, I mean a state in which the production and use of fossil fuels is so critical to both its economic activity and its political elite that any suggestion to transition to non-fossil fuels is viewed as a threat to its way of life. The energy markets between the United States and Canada have long been very closely-linked, and the logic of petrostate politics is everywhere on either side of our border.

In 2018, the United States was the largest producer of oil, and Canada was the fourth largest. Both countries supply most of their own fossil fuels, but when we do import, it is typically from the other. Canada has the third-largest oil reserves in the world. The United States has the fourth-largest natural gas reserves in the world. By all accounts, the amount of fossil fuel production in both the United States and Canada is increasing, at the exact moment scientists tell us we need to move in the other direction. Petrostate ideology requires certainty that these future projections will not be altered by a concerned, outraged, and informed public, to the point where it pathologizes anyone it perceives is an enemy. You can see examples of this everywhere such as the Alberta Inquiry dedicated to investigation of alleged foreign funding of environmental activism, or the increase in US legislation that would increase criminal penalties against nonviolent pipeline protesters.

In a petrostate, the logic of fossil fueled capitalism is so strong, it even allows allegedly progressive leaders to occupy remarkable heights of cognitive dissonance.

Barack Obama famously bragged about speeding up oil and gas permits as an “all of the above” strategy, and Justin Trudeau claimed “no country would find 173 billion barrels of oil in the ground and just leave them there.”

I bring up these examples to point out how deeply embedded the logic of protecting the petrostate is, even among politicians who acknowledge the reality of climate change. The petrostate is so powerful because of how it systematically hides not just its infrastructure but the information about its infrastructure. If the information about its infrastructure and operations were more easily available to the public, that information could and would be used against it, both in the court of public opinion and potentially, in an actual court of law.

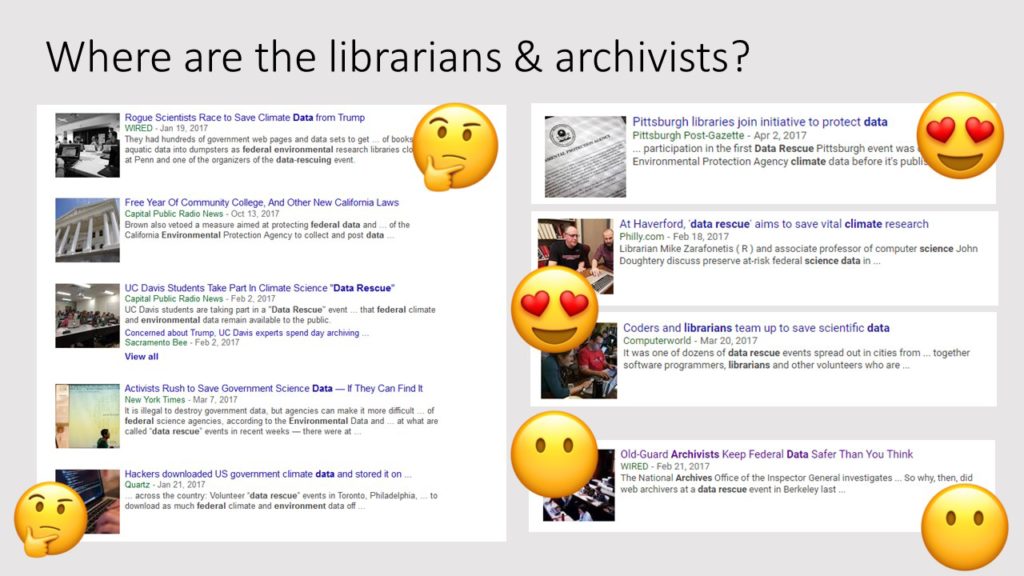

So where does this leave librarians and archivists in the world of petrostate politics? There are a number of things we could do, and I could list them on a final slide for you, but I think that’d be a little too easy. The challenge ahead is immense, and a to-do list seems a little too superficial for what we have ahead of us. Instead, I’d like for us to consider a serious shift in how we view our professional identities so we can consider how to better serve the public.

One of my eternal concerns with librarians and archivists is that we define our professional identities by the tasks we perform for our employers, as opposed to the fundamental nature, and importance, of our work. We repeat the things that our employer has placed in our job ads, such as, “I develop retention schedules for my university” or “I run checksums on the files ingested into the digital preservation repository.” What is more rare is for us to discuss our work in a way that evokes our trade; that is, that regardless of our title, we are ultimately all information workers.

When we identify too closely with the specific duties of our job descriptions, we let our employers define our professional identities – and therefore our professional responsibilities – for us. Furthermore, identifying as an information worker allows us to extend a critical lens to how information is stewarded outside of the institutions we work in. In the United States, the advocacy of healthcare workers for single payer healthcare has become a powerful force, as these workers have a unique moral and professional authority when they call for access to healthcare as a universal right regardless of the ability to pay. We need a similar advocacy effort of information workers to insist on the decommodification of information; that information in the public interest should be accessible to the public – even if it was information created by the private sector.

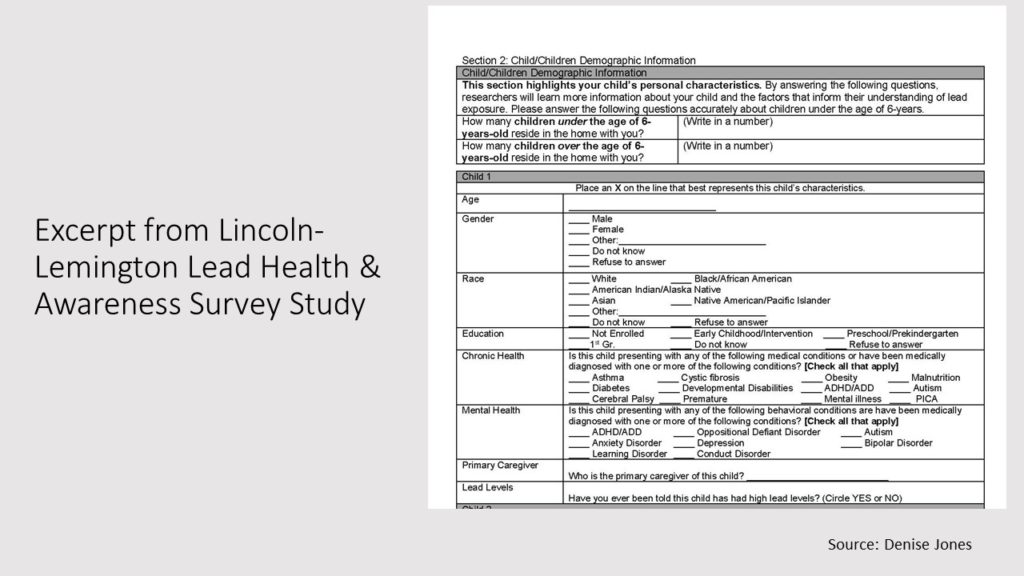

As librarians and archivists, everyone in this room has unique skills you can bring to whatever environmental justice issues are taking place wherever you live. I have been involved in a number of local water issues in my hometown, and because being an information worker is such a core part of my identity, I have used my skills as an archivist to track down historical reports and data to bring to public hearings to enter into the official comments. If you know how to work with a library catalog, or large messy data sets, or data visualization, you have some of the most prized skills that environmental justice organizations wherever you live desperately need help with. If your province or state is considering changing regulations that would impede access to environmental information, you have the professional credibility as an information worker to speak out and organize your fellow information workers to stand against further commodification of information. Perhaps one day, we can create a binational group of information workers dedicated to tactics that prioritize the decommodification of environmental information and expropriation of environmental information from the private sector.

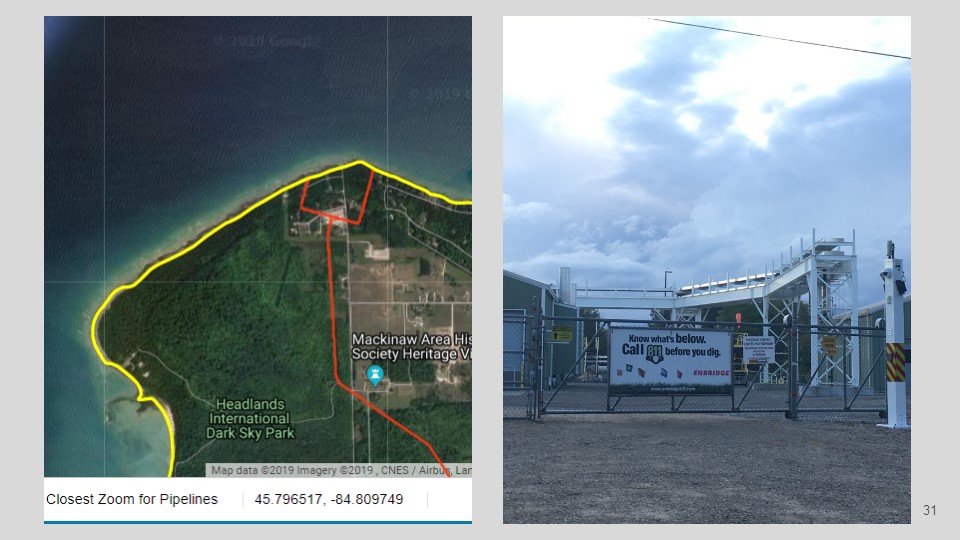

Sometimes we will fail to get information that we need, and then we will need to learn other creative ways of obtaining it. A few weeks ago, I spent some time camping in Michigan near the Straits of Mackinac. You’ll recall that it’s impossible to get the specific location of pipelines because you can’t zoom in all the way. And while technology shapes how we understand infrastructure, it doesn’t always have the final say, especially if you learn how to read the landscape.

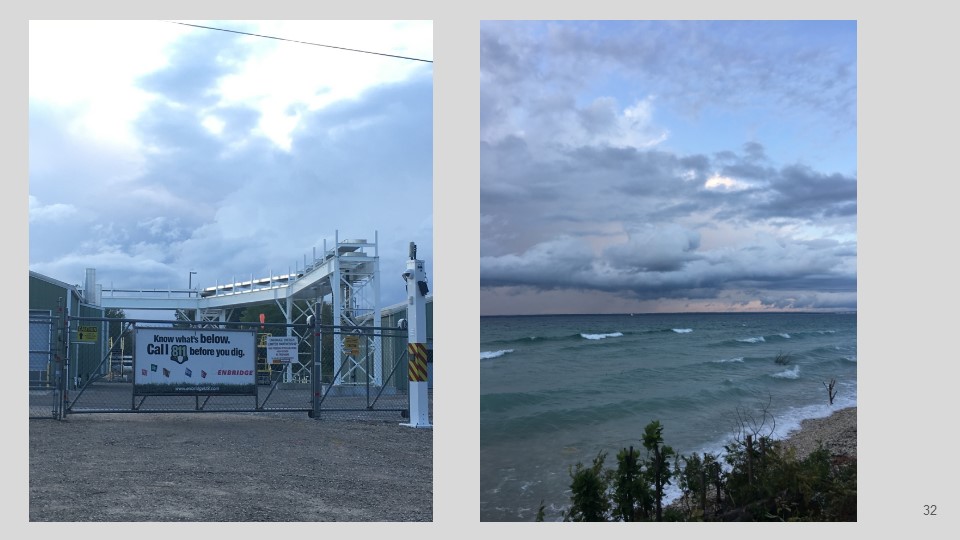

I wanted to get as close as I could towards near where the pipeline was in the straits and where it came on land. I looked at the map and saw that the nearest landmark was a lighthouse near the shoreline. On the way to the lighthouse, I found an Enbridge power station.

I drove down to the water just over the hill to see if it was possible to see where the exact point was that the pipelines went from the lake bed into the shore line – I knew they would be buried but figured there would be a marker post. I found a woman and started talking with her, and she pointed down a few hundred feet to say that the pipeline markers were there. The water has been very high on the lakes lately, and I didn’t think it was safe for me to go further.

So I went back to my car, drove back up the hill, and turned off to the road going behind the power station. And finally I found where the pipeline was – not because it poked out of the ground, and not because of any large sign, but because of who was on top.

A family of deer was nourishing themselves on the grassy meadow growing on the right of way above this pipeline that many people view as a ticking time bomb . And as I looked at the deer closer, I could just make out a post marker hidden in the meadow grass.

Sometimes there is no way to get information about the environment because of the system we live in which says that corporations have more right to make money than your right to know what is happening to the hidden infrastructure all around us. But even with this petrostate logic, there is no substitute for paying attention to the land, and the air, and the water around us. Sometimes despite the logic of commodification, the information is right in front of you if you know where to look.