A Green New Deal for Archivists

I gave this (Zoom) talk to my friend Rick Prelinger’s “Archives: Power, Justice, Inclusion” course at UC Santa Cruz in early May. I’ve long been fascinated by the New Deal and this was a good opportunity to put some flesh on an idea I’ve been talking about for a while now.

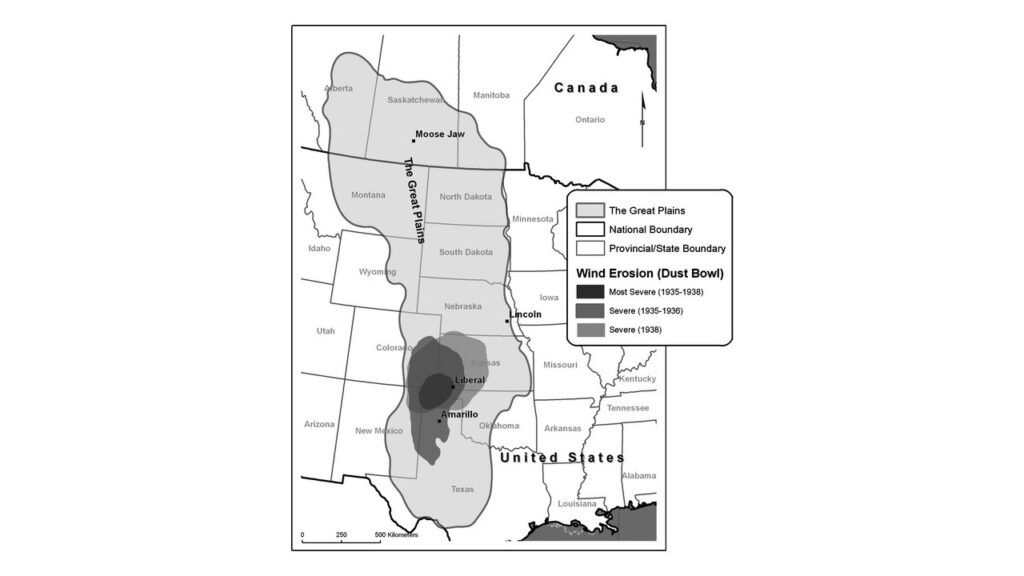

DUST BOWL AND CRASH OF 1929

I want to start with this image.

It’s obviously from a long time ago. The clothes look a little older, almost everyone is wearing a hat. One man has an arm band on with a cross on it.

If you had showed me this picture a couple weeks ago, I might have glanced at it and thought it was either the flu pandemic of 1918. Or maybe a wartime photo from WWI or WWII, perhaps a group of medical workers shielding themselves against chemical weapons.

This picture was taken during the Great Depression in the state of Kansas. The year was 1935. The residents of this small town are wearing gas masks to protect their lungs from air pollution, and they are in front of a Red Cross building. At the time this photo was taken, the unemployment rate was around 20%. Just a couple years before the unemployment rate was closer to 25%.

At that time, Kansas was in the middle of what was called the Dust Bowl, which was the site of one of the worst environmental catastrophes in US history.

The Great Depression was a worldwide economic depression that started in 1929 and lasted through the 1930s. The Great Depression started when the stock market crashed in October 1929. As prices began to decline for the value of goods across the country, the price drops eventually affected the wheat crops grown in the Great Plains states. As the value of wheat dropped, farmers plowed up more acres to put into production to make up for the lost profits. Initially there was a huge harvest of wheat, but the over supply of wheat led to an even greater drop in wheat prices.

In order to grow the wheat in the first place, farmers removed the prairie short grasses that had helped hold the soil in place. Many areas of this region also experienced drought. These forces combined to create massive dust storms that look like something out of a horror movie. One of the dust storms were so big they went far east and even reached Washington DC and New York. The devastation of the region made thousands of families homeless, and they migrated out of the region, including to places like California’s Central Valley.

https://cdm16786.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/lee/id/269

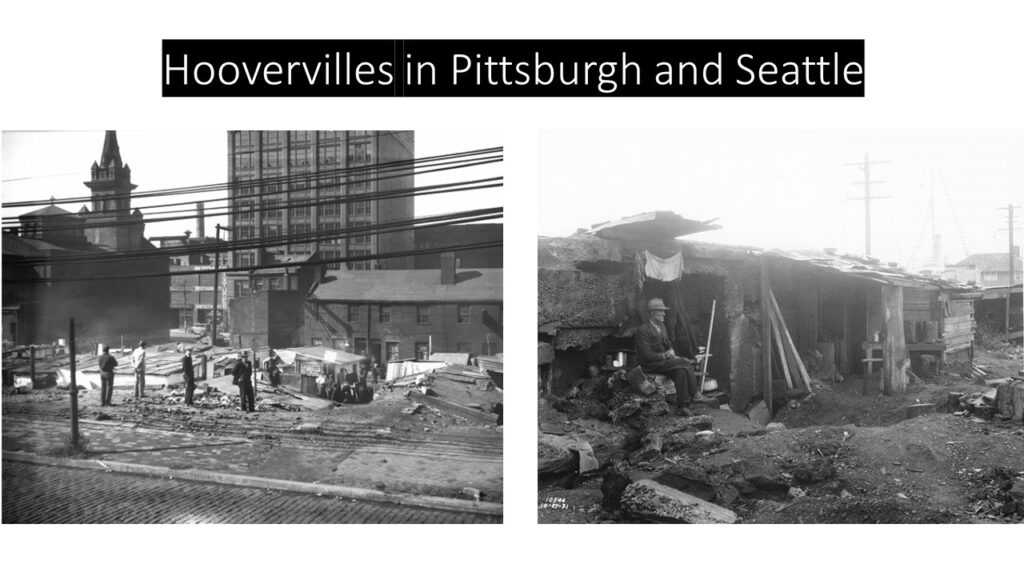

Three years after the stock market crashed, millions of Americans were out of work, and so many had lost their homes that homeless encampments and slums popped up all around the country that were nicknamed Hoovervilles, which was a reference to President Hoover’s failure to meet the challenges of the Great Depression. In 1932, Franklin Roosevelt (or FDR), the governor of New York, ran against Herbert Hoover and won in a landslide election in 1932.

ELECTION OF FDR AND THE NEW DEAL

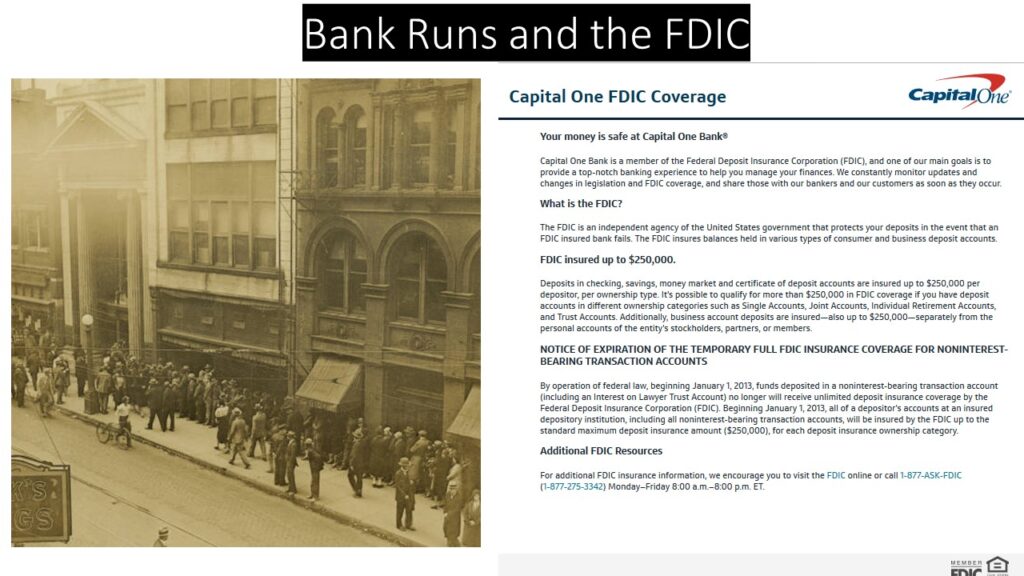

One of the first acts that the Roosevelt Administration did was to attempt to stabilize the banking system, which was on the verge of collapsing. In the early part of the Depression, there was no guarantee that if you had deposited your life savings in your neighborhood bank that you could get it out. After the economy began to fall apart, people would panic and go to the bank to withdraw their money. If too many people did this, then it could result in the bank literally running out of money and going bankrupt. During the Depression, 1/3 of banks failed and depositors lost over $1 billion of their deposits.

Immediately after FDR took office in early 1933 was he closed down the banks for several days as a way to alleviate panic while Congress and the White House pulled together legislation to stabilize the banking system.

If you’ve ever deposited something in your bank you’ve probably noticed a little logo that says something like “Member FDIC” or “Your deposit is safe and guaranteed under FDIC.” The FDIC was established to insure banks so that you would not lose your deposits.

As the FDIC and other measures to stabilize the banking system were implemented, storms in the Dust Bowl continued to get worse in 1934 and 1935. The Dust Bowl wasn’t the only place experiencing agricultural collapse – across the country, other farmers grappled with how to handle surplus crops and livestock while prices cratered, and many tenant farmers, especially black farmers in the South, didn’t own the land they were farming on and experienced economic calamity.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gordon_Parks#/media/File:Gordon_Parks_-_American_Gothic.jpg

To respond to the problem of soil erosion and farmer poverty, FDR’s administration launched a number of programs that included everything from resettling farmers to different areas, to teaching them different agricultural practices to conserve the soil, to paying farmers not to plant crops in order to control prices.

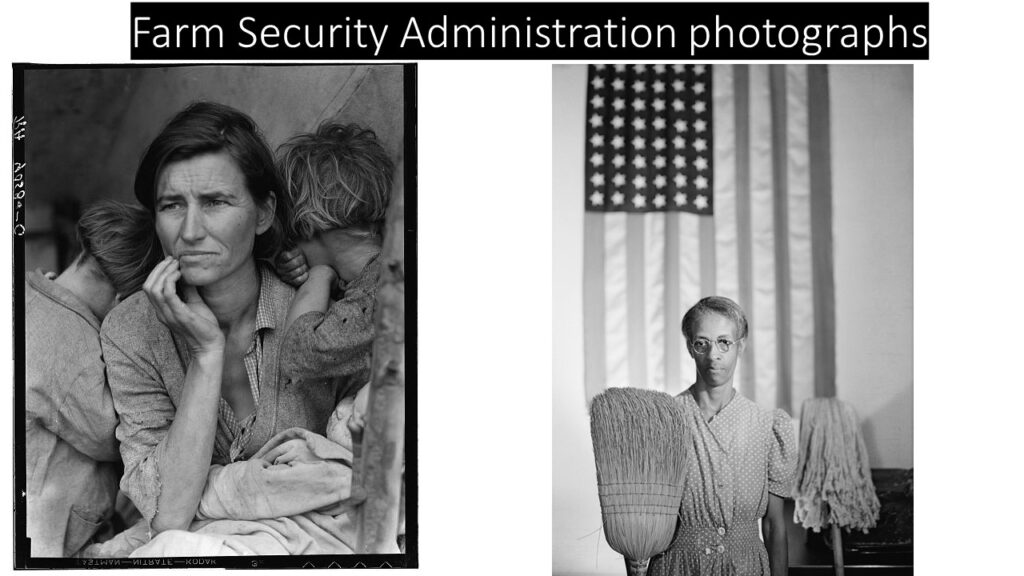

One of the agencies created to help farmers was the Farm Security Administration, and it hired many photographers – photographers who today have their work in famous museums, like Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Gordon Parks – to document both the poverty in rural communities as well as the impact of the government programs.

Over time, all of these programs that FDR’s administration implemented became collectively known as the New Deal. One of the most important ones was signed into law 85 years ago yesterday, on May 6, 1935. This was a program known as the Works Progress Administration. This was a program that created government jobs for millions of Americans who were unable to find paid work during the Depression. Remember – at its peak 1 in 4 American workers were unemployed, and so the WPA literally kept many families from starving and becoming homeless by giving them jobs that paid enough for them to get by.

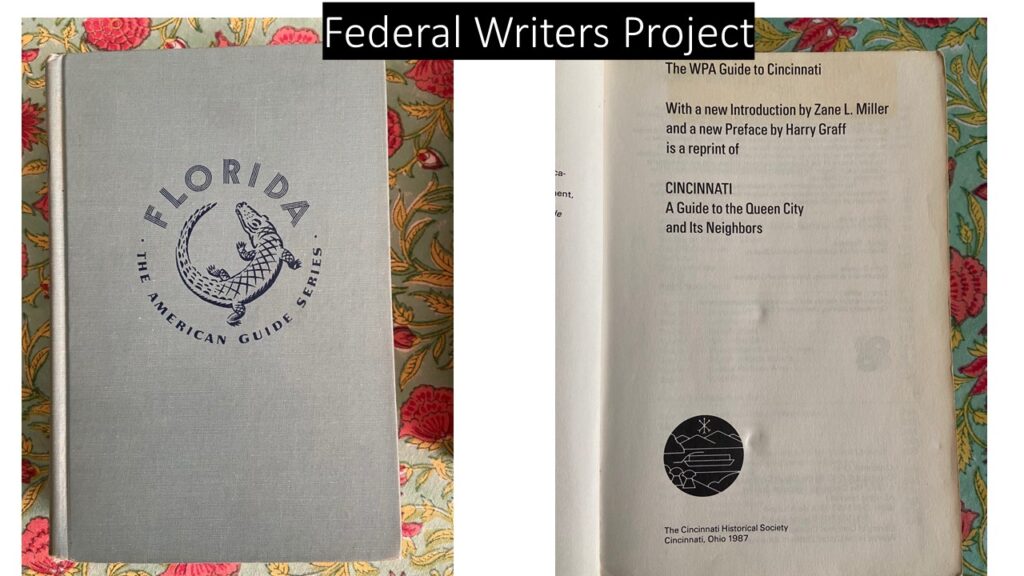

The WPA was an umbrella of programs that employed everyone from construction workers to help build bridges, dams, and schools to librarians who delivered books on horseback to musicians and playwrights who performed public concerts and plays.

In addition to writers, the WPA also hired scores of archivists as part of a program called the Historical Records Survey. The Historical Records Survey began in 1934 as part of the Federal Writers Project. It was directed by Luther Evans, who would go on to become the Librarian of Congress and UNESCO director.

https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p267401coll34/id/5475

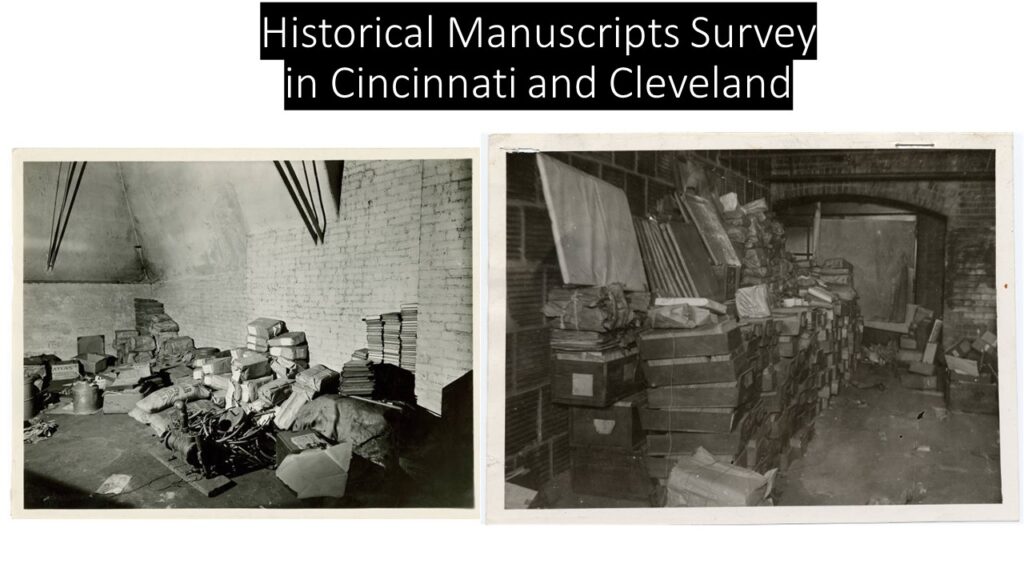

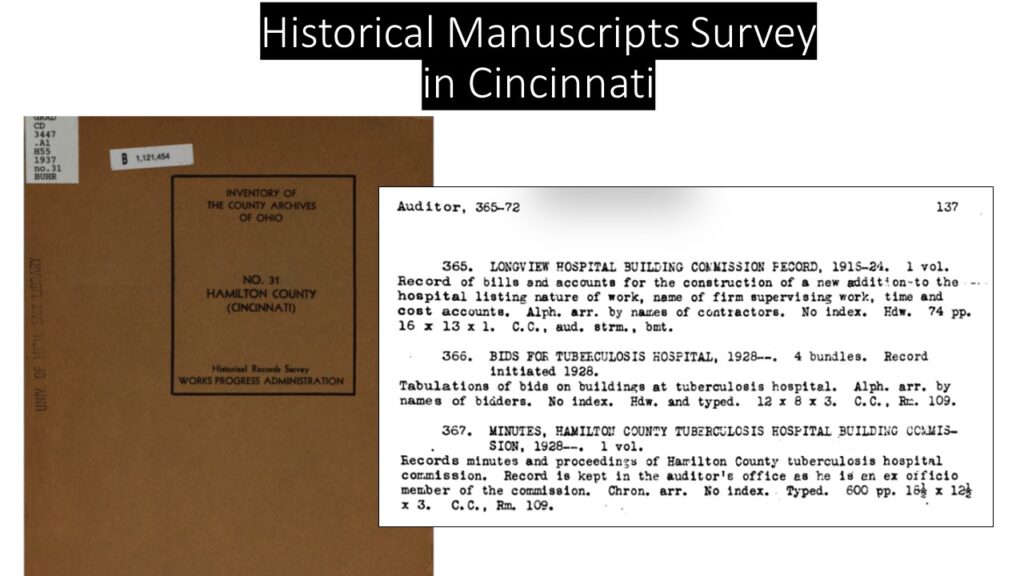

The Historical Records Survey had two major programs: a survey of federal records located in offices outside of the Washington DC area, and a survey of state and local records. The first part was important because the National Archives officially became a federal agency in 1934. The National Archives needed to identify the various federal records floating around, and this part of the Historical Records Survey helped it track down and consolidate records.

The largest achievement of the Historical Records Survey was surveying county records – of the 3,066 counties in existence at the time of the survey, fieldwork was completed for 90% of them. WPA workers carried out the field work by going to county courts and administrative agencies to determine what kinds of records existed, where they were located, and a short description of the records. The field work also generated significant information about the history of the states and their counties. In some areas, municipal records surveys were also completed, such as for the city of Cleveland. Although there had been some attempts to survey America’s local and state records before (mainly through the efforts of the American Historical Association’s Public Archives Commission), the WPA Historical Records Survey was a significant advance in trying to establish a comprehensive picture of the overall condition of America’s public records and archives scattered across the country.

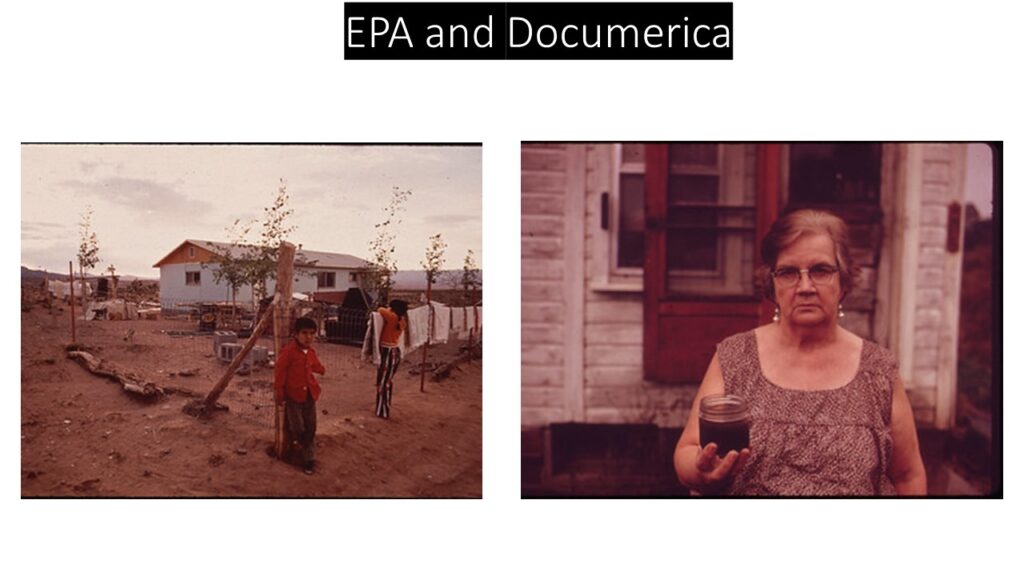

The WPA and other federal government jobs programs ended with the entry of the US into WWII. But it wasn’t the last time the federal government would pay people for documentation efforts. In 1970 the Environmental Protection Agency was established.

https://flic.kr/p/6K4sEP

A few years after it was established, the agency hired photographers to document the state of the environment in the United States. Photographs had already begun spurring new environmental awareness around the time of the EPA. These photos were intended as a visual baseline to show how the American environment looked before the implementation of laws like the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act. Documerica photographers, like the Farm Security Administration photographers, were given a wide range to photograph people in relationship to the environment.

Having a handle on the way records and documentation were integral parts of addressing both environmental calamity and deep inequality is critically important because it helps us understand the role that archivists and other allied professions like librarians, oral historians, writers, historians, and photographers could play in the future.

The United States is almost certainly experiencing the highest unemployment rates since the Great Depression. We won’t know the full extent until the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases its numbers for April this Friday. But there are early projections suggesting that the new numbers are 16%. To compare, the peak unemployment rate during the last major recession between 2008-2009 was around 10%.

One of the things that was remarkable and profound about the New Deal is that it validated that people like writers and photographers had just as much a right to make a living from their work as other occupations.

In the last few years, activists concerned with the combined problems of climate change and economic inequality have proposed a Green New Deal. At the heart of the Green New Deal is the goal of a massive scale investment to transition the United States economy and infrastructure away from its deep dependence on fossil fuels to renewable energy, involving every sector for agriculture to transportation. Right now the Green New Deal is more a set of ideas than a political program. Partially this is because to replicate programs at the level that FDR implemented, we need to have a President and Congress that is fully on-board with these measures, and the political establishment over the last 40 years has been a retaliation against New Deal political philosophy that envisions a government that actively works to level the playing field between rich and poor.

Right now, most proposals for a Green New Deal are arguably narrowly focused around infrastructure, agriculture, energy generation, and transportation. There isn’t much yet that envisions a renewal of something like the Federal Writers Project or the Historical Records Survey. So let’s consider what a blueprint for a Green New Deal for archivists and information workers might look like.

A GREEN NEW DEAL FOR ARCHIVISTS AND INFORMATION WORKERS

Compared to when the Historical Records Survey was carried out 80 years ago, archivists have come a long way in terms of our skill sets and knowledge. We also have many examples of archival projects that aren’t just records from federal, state, and local governments – we also have new projects like community archives. A GND for archivists and other information workers could put archivists to work doing a wide variety of projects. The following are just examples, and if you think of your own I hope you’ll suggest them as well at the end.

Archivists as research partners to guide policy decisions

- Many GND plans call for funding investments in environmental justice projects. Environmental justice is the principle that many polluting industries or toxic waste sites have been disproportionately located near poor communities and communities of color. Archivists could be research partners in identifying and locating records that would help establish a priorities list in every community for environmental justice investment.

Data management partnerships for scientists

- In order to preserve as much of the scientific findings that continue to unfold around climate change, it’s imperative that the underlying data are managed and preserved so that it can continue to be validated and reused well into the future. Archivists and librarians in universities have significant experience in data management planning and digital preservation. Deploying archivists and librarians trained in these skills at large levels to all research institutions would ensure that climate and environmental data are preserved for future use.

Bioregional documentation strategies

- Building on the past examples of the Federal Writer’s oral history projects, and the photography of the Farm Services Administration and the EPA’s Documerica, we could employ archivists, historians, photographers, and other information and creative professionals to document the environmental state of America’s different bioregions. Bioregions are areas that are defined by environmental commonalities, like tree species or watersheds. I live in the Ohio River valley watershed, and so in this example, perhaps archivists could work to document the industry along the river, photograph different areas along it, look at archival collections in existing repositories to identify all Ohio River related archives already in existence, and so on.

- The idea of doing documentation projects on a bioregional basis is because a project like this would be meant to capture the experience of everyone living adjacent to an environmental feature. The Ohio River Valley crosses multiple states, and therefore having documentation projects that conform to political boundaries would mean you could not adequately document a bioregion.

Establishing appropriate archivist and records staffing for government archives

- One of the long-standing problems within the archives and records field is that government archives and records centers that hold vital records – meaning things like birth, marriage, and death certificates, veterans records, and property records – are chronically and severely understaffed. This has serious consequences as we continue to experience environmental changes. Many of these government archives have microfilmed or digitized their records, but not all of them have. As a result, if a terrible disaster like a hurricane, flood, wildfire, or tornado – many of which could become more severe as a result of climate change – were to hit the archive, it could seriously impact their ability to provide their constituents with records.

Partnering with emergency management and planning authorities for inland migration

- We know that even if we act very quickly to deal with climate change, there is some degree of sea-level rise due to climate change that is inevitable at this point. A few years ago I co-authored an article examining climate change risks to archives, and we found that over 20% of archives were at risk to either storm surge from hurricanes or sea-level rise. Planning for inland migration is already far behind where it needs to be in the United States, and no one has really solved the question of what to do with a city or county’s records if that area has to ultimately be abandoned. Should its records go to the next county over? Or to the state archives? Archivists could and should be involved in planning what should happen to records from the earliest stages of planning.

- We also know that many historic sites along coastlines could be permanently lost due to sea-level rise. Under a GND, one of the highest priorities would be documenting those sites through video, photography, oral histories, and other forms of documentation of places that will no longer be reachable due to sea-level rise or erosion.

Right now it’s tremendously difficult to imagine a world in which we’d not only mobilize all levels of the government to deal with climate change and poverty but to also hire archivists en masse to document it. And yet I like to think of Naomi Klein’s remarks from her book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate where she says that our fear may paralyze us and make us want to run, but we have to give people something to run to, and that’s why I think it’s still worth talking about not just a Green New Deal, but the role that archivists and archives can play in the transition from one world to the next.

Categorised as: archivists