White women screaming at Elizabeth Eckford during the integration of Little Rock High School, 1957

White boys smirking at Nathan Phillips during the Indigenous Rights March, 2019

It’s a rare event to see a headline originate in Indian Country Today, then pop up a few hours later in Cincinnati media channels, a few hours later on the Facebook feeds of progressives and leftists I know around the country, and finally the New York Times. The story making headlines was how a number of Covington Catholic High School students, in Washington DC for the March for Life were harassing a group of indigenous activists also in town for the Indigenous People’s March – an event meant to highlight many of the concerns of indigenous people, including the immense numbers of murdered and missing indigenous women. The videos on social media were even worse than I was prepared for, and the gleeful mob mentality of a bunch of mostly white high school boys harassing indigenous elders should be a wake up call for everyone who thinks that racism is a generational issue that will eventually go away when the current FOX news demographic peters out.

Something that I think is missing from the national coverage is that there is something deeply and disturbingly evocative of Cincinnati’s culture within the actions of the young men. We need to talk about Cincinnati suburban white flight and the role of parochial schools. Because if we don’t acknowledge this, then we’re only going to keep seeing this happen over and over.

Suburban white teenagers doing racist things keeps happening over and over and over in this region. For non-Cincinnatians, Covington Catholic is in Northern Kentucky, and Northern Kentucky is very much a part of the greater Cincinnati region. Lots of people live in Northern Kentucky who commute across the river to work in Ohio, and vice-versa. At Mason High School (a public school in a northern suburb), black kids received targeted racist SnapChat messages last January. At Kings (another suburban high school), white basketball players wore jerseys with racist slurs on them. A month later, Elder High School (a Catholic high school on the west side of Cincinnati) students chanted racist and homophobic slurs at a rival Catholic high school’s players during a basketball game.

Sometimes, it’s also the adults engaging in this. A Mason teacher told a student he might be lynched. At Kings, a teacher joked about a student being deported. And when students try to speak up, to be on the side of social justice? Sometimes adults try to shut them down – like one Northern Kentucky student at Holy Cross High School, who was barred from giving a speech school authorities deemed as “political and inconsistent with the teaching of the Catholic Church.”

What do all of these schools have in common? Some of them are public, some of them are parochial. But all of them are extremely white, reflecting the fact that with a few exceptions, white people who live in the greater Cincinnati area by and large do not send their kids to Cincinnati Public Schools (CPS) – the largest educational environment in the region where white kids would routinely encounter plenty of students who don’t look like them (and the schools that white CPS parents favor are getting whiter).

White people sending their kids to white schools is not a new or unique phenomenon to Cincinnati. It is often perpetuated by where white people move – the suburbs – that are very white. The growth of suburban development is directly linked with white people exiting the city and seeking “good schools” combined with government policy that helped create racially segregated housing patterns. The suburban sprawl around the city of Cincinnati is very white – while Hamilton County (where Cincinnati is located) is around 66% white, the surrounding suburbs are more than 80% (and sometimes more than 90%) white.

But even when white people live in more diverse areas like the city, they still take steps to send their kids to white schools. According to this story in the Atlantic, 2/3 of urban schools are non-white, which is pretty similar to the numbers within Cincinnati Public Schools (approximately 63% Black, 6% Multiracial, 5% Latino, 2% Asian/Pacific islander, and 0.1% Indigenous). I am not a demographer, so the following is some rough back of the envelope math. According to the Census, Cincinnati’s city population is 50% white. Yet the CPS enrollment of white students as of a couple years ago was around 24%. There is obviously some kind of disparity here, between the white population that lives within the city and where their children go to school. Again, I am not a demographer but I suspect that for white parents who live in the city, the disparity is at least partially, if not wholly, explained by white parents who send their kids to private schools – particularly parochial schools. Unfortunately, it is hard to do back of the envelope math for this one, as the state of Ohio only collects data for public schools.

Research shows that white kids who live in diverse areas and go to diverse schools are way more sensitive about the historical and current impacts of racism in American life. You can have a great curriculum that talks about the history of land expropriation from indigenous people, about redlining of neighborhoods that kept out people of color, immigrants, and Jews, of highway construction projects that destroyed black communities – but lived experience is a greater teacher than curriculum. And when white kids are mostly interacting with other white kids in an environment where white parents are choosing to live around other white people, white kids doing racist shit is almost inevitable.

Let’s talk about parochial schools in Cincinnati, because I think this part is critical to understanding what happened in Washington DC.

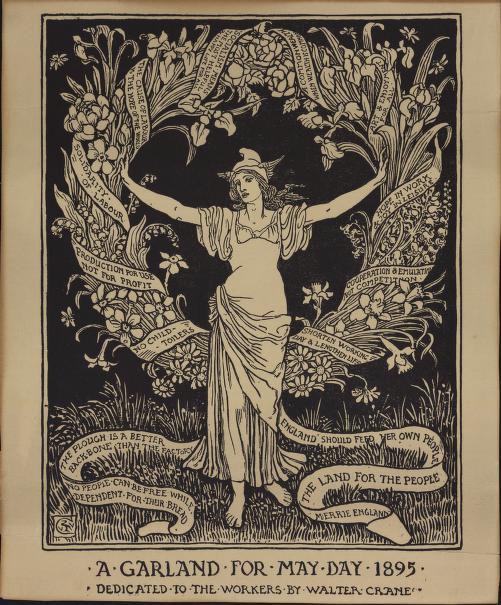

Cincinnati’s historical relationship with Catholicism runs very deep. Parish social events are a massive part of the social fabric of the city. It is not unusual to see many people with ashes on their forehead on Ash Wednesday. During Lent, many parishes have Friday fish fry dinners that are open to the public. On Good Friday, there are television crews at a historic church high up on a hill where people climb the stairs and pray the rosary. During the summer, parishes have huge festivals that serve as fundraisers for the parishes’ activities. Many parishes with large festivals also run schools.

There are so many Catholic schools just within the Archdiocese of Cincinnati that as of 2013, it is now the sixth-largest parochial school network in the country, despite the Archdiocese being the 44th biggest Catholic diocese. There are over 100 Catholic schools within southwest Ohio. Across the river in Northern Kentucky, the Diocese of Covington (part of the Archdiocese of Louisville) has over 30 schools.

The modern anti-abortion movement also has deep roots in Cincinnati, and it is deeply tied to the presence of Catholic institutions in the city. John Willke was a major figure within the anti-abortion movement, starting one of the country’s first Right to Life* chapters; Willke was educated at Roger Bacon, one of Cincinnati’s Catholic schools. The Archdiocese of Cincinnati’s approach to the sanctity of life reveals a nearly monomaniacal obsession with abortion – despite the fact that Catholic social teaching routinely calls for also opposing the death penalty, calling for an end to rampant militarism, and taking action on climate change. When you take a look at the Archdiocese of Cincinnati’s webpage about life issues, it is overwhelmingly concerned with abortion. The Catholic Telegraph, the Archdiocesan newspaper, is also almost exclusively concerned with abortion in its section devoted to life issues.

Legislation to end abortion is about one thing: universal imposition of a particular set of political and religious beliefs on others who do not share these beliefs. For all their handwringing about morality, it bears repeating that many religious groups do not share the Roman Catholic clerical opposition to abortion, and in fact, and many Catholics themselves support abortion access (according to 2018 figures, about 51% of them).

One thing I wish people outside of Cincinnati knew is how much parochial schools are involved with anti-abortion activities. The Cincinnati Archdiocese provides significant support for local teenagers to attend the March for Life and Catholic Telegraph has slideshows depicting smiling groups of mostly white local Catholic high school teenagers in DC, and for those who couldn’t make it due to weather concerns, cheerfully grinning and holding up signs declaring ABORTION KILLS CHILDREN in front of the local Planned Parenthood clinic that is the last remaining abortion provider in the region.

I think it’s the grinning that sets me off the most, because it’s so similar to the smirk by the young man standing in the way of the indigenous elder. I can’t decide whether it’s the gleeful naivete of young people who have no idea what they’re talking about, or if it’s the gleeful arrogance of young people who have been recruited into the ranks of ideologues. Either way, it’s a stance that serves to close off any recognition of perspectives contrary to what these young high schoolers have been told are the only moral ones by every adult authority figure in their life.

That’s ultimately what this comes down to: mostly white, mostly middle to upper-class, mostly suburban young people being told that they are on the side of righteousness and morality. This stance is what is taught in schools, what is taught in their churches, what is taught in their homes. When someone who doesn’t look or think like them interrupts this world view, they are turned into an obstacle to confront and stare down, not a new perspective to listen to, and learn from. This is what is so jarring about the young men harassing the indigenous elders – despite the protestations of the school and the Covington Diocese that the MAGA students don’t represent their teachings, to the contrary – they’ve been exceptionally well-trained in the art of imposing a singular world view on others.

Whenever these stories come up, someone always asks, “Where are the parents?!” I’d suggest that they are right there in the middle of it all – living in white areas, sending their kids to white schools, and perpetuating a belief system that it is OK for children to harass others who don’t share their sense of white patriarchal systems of control. Over and over, I hear as a childless person I am not supposed to criticize other people’s parenting choices. But as a white person committed to ending white supremacy, I don’t see how I have any choice but to question parenting decisions that reproduce systems of racialized and gendered authoritarian control. What’s good for one’s children may just be poison for everyone else who has to live with them.

1 Comment