What men don’t do

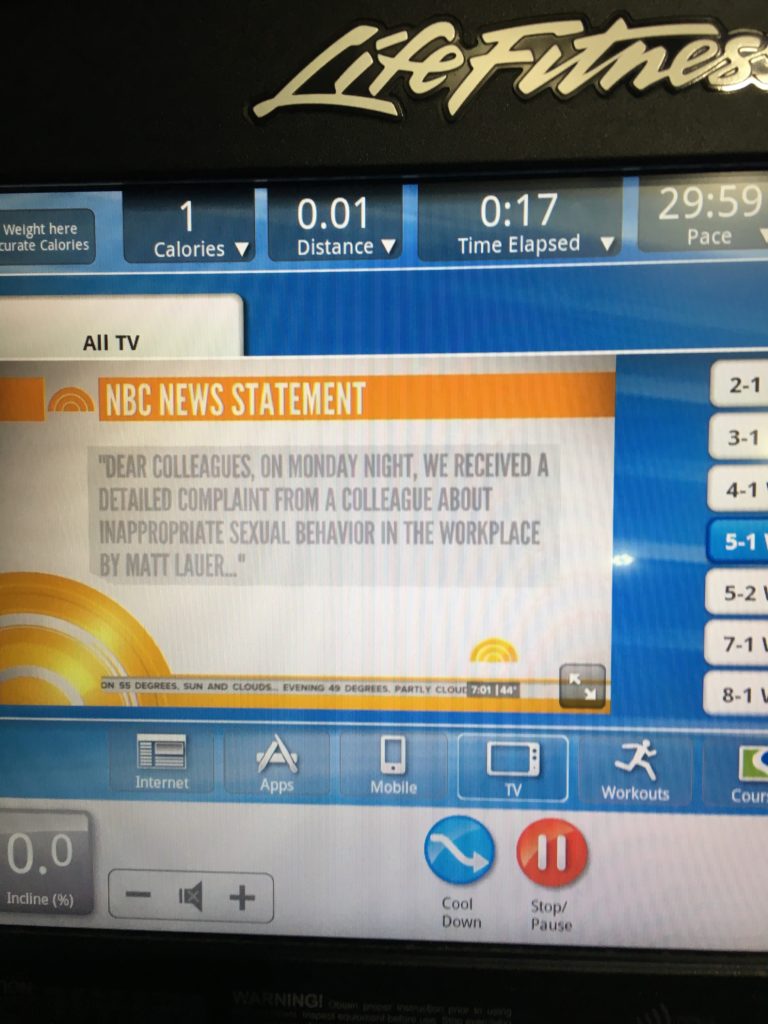

Since the Me Too revelations last year, it’s become obvious how pervasive and all-encompassing misogyny is that most men only recognize its presence by its most violent manifestations. The prevalence of rape and sexual assault is a moral and public health crisis. It has to be eliminated. But the enormous amount of sexual and gender-based violence does not exist in a vacuum; it is a product of a misogynist culture that every one of us is marinated in from head to toe, from cradle to grave.

Rape is one of the most brutal and violent forms of misogyny, but eliminating rape and sexual assault will not eliminate misogyny. And this is where I find myself turning in circles. Although it’s been several years since I have had direct experience with threatened or actual physical violence by a man, the men in my life routinely act in ways that dehumanize me and other non-men. I believe that violence against non-men exists on a spectrum, where ignoring the needs and undermining the work of women and nonbinary people creates a subtle foundation for more overt acts of violence. Not all men commit acts of overt violence, but all misogynist-based violence is rooted in the dehumanization of non-men. And many men are exceptionally skilled at daily acts of dehumanization.

I spend a lot of time thinking about the ways in which the vast majority of my male friends, relatives, coworkers, and comrades routinely disappoint me and let me down. This probably isn’t healthy; it’s honestly pretty depressing. I also doubt I’m the only woman who does this. As a socialist feminist, I believe a better world is possible, and making a better world means prioritizing the healthy ways in which men, women, and nonbinary folks can build liberatory relationships with one another. Over the last year I’ve tried to articulate the common qualities among the men I enjoy spending time with, who I feel safe around, and who I trust.

I want to be clear that this list is not a shortcut or way to instantly eliminate misogyny. Men can still do all of these things and perpetuate misogyny. But it’s telling that I can count on one hand the men I know who consistently do all of these things:

1. They consume media, art, music, journalism, literature, and ideas by women and nonbinary people as much as men

From popular culture to various literary canons, the work of men predominates most of what we read, see, hear, and think about. It’s intellectually lazy and embarrassingly boring to only read and watch and listen to shit created by people like you. Casting your media consumption net wide and far helps one empathize with perspectives that are not their own. ALSO it seems like (most of) the men I know somehow have more time to read than (most of) the women I know, probably because they have less caregiving duties in their life (in which case, holler at me, I have hundreds of books from my dad’s library I need to find a good home for).

Women writers and artists and musicians are constantly having to fight against the notion that their work is somehow specifically feminized because of who created it, while men are more often afforded the honor of creating “universal” work. When men enthusiastically consume the work of people with different gender identities, it normalizes the idea that work written by people other than men has universal appeal.

2. They publicly cite and promote the work of women and nonbinary people who they aren’t related to or trying to profit off the relationship, and they trust the expertise and leadership of genders different from them

This is a huge one for me, partly because I work in higher education, and repeatedly during my life I’ve been one of a handful of women in men-dominated leftist groups that have veered uncomfortably close into toxic masculinity. Citing my work has major material benefits for me professionally. It’s really important that it’s not just me saying “I am a leader in my field, here are some articles I wrote” but to have leaders in my profession, which includes many men, behind me saying “Eira is a leader in our field, the article she wrote had XYZ impact on the profession.”

In political work, I need men to trust my expertise and to trust non-men’s leadership collectively. Leftist men who gatekeep and hoard cultural and social capital in political work are far more of a threat to leftist organizing strength than any right-wing troll. If your organizations and coalition-building activities don’t reflect the overall gender distribution of your corner of the world, and you aren’t concerned about fixing that, good luck with pulling off the revolution.

3. They volunteer to Do The Work and then actually do it

I have a tendency to take on a lot of work (no doubt part of gendered socialization) in the various professional and political arenas of my life, though I’m getting better at drawing my boundaries and making my limits visible. The men in my life that I really appreciate often say things like “I want to ensure this work isn’t totally falling on you, how about I write the first draft/call this person/organize this meeting?” Note: this is very different than saying “tell me how I can help.”

Telling someone you can help without a specific offer of assistance places the burden back on me, and then it’s easier to just say “No, I’m okay” instead of sitting around thinking of what I can delegate. The other thing the men I appreciate do is that they follow through. If they’re not going to make a deadline because Life Happened they’re proactive about letting me know when they’ll Do The Thing so I don’t have to ask them what is going on. I’m beyond overwhelmed with everything I’m trying to juggle between caregiving for my elderly father, dealing with the eternal “doing more with less” mandate of working in public higher education, maintaining my own sanity and relationships, and surviving late-stage capitalism. Men who don’t shoulder their fair share of the work, or men who say they will and don’t, make my life much more difficult.

4. They do emotional labor

Emotional labor is an expansive term, but from my perspective, it’s all of the small ways in which one tends the garden of their various relationships, professional, romantic, friendly, comradely, and neighborly alike. A garden requires planting new seeds, weeding harmful things, paying attention to it, and feeding it through sunlight, water, and nutrients.

Our relationships are the same way. Offering a hug to someone who is going through a rough time, remembering your family’s birthdays, checking in with a friend you haven’t heard from for a while, inviting people at work to go to lunch with you, expressing appreciation for both the daily work of others and when they go above and beyond – these are all vital acts of emotional labor that pay off enormously in building solidarity with one another. It means a lot to me when men at work ask me about how my father is doing even if it’s been weeks since the latest eldercare emergency, or when men from other areas of my life ask me about a specific workplace challenge I mentioned months ago. Women are very much socialized to do these things, and we tend to give more emotional labor to men than we receive in return. It is absolutely vital and world-repairing work that men need to take on.

These are the things I wish more men would push themselves to do – and hold other men to the same standards. Our collective lives and freedom depend on it.